30 things I learned in November 2020

1: I’ve managed to keep a series of posts on my blog running for a year rather than giving up after about a month.

2: William Barr is someone we may be hearing more about in the coming days.

3: I recently read Lawrence Douglas’s Will He Go? and the first 24 hours after the polls closed in the US presidential election have been just as mad as he predicted. But I wasn’t convinced by Douglas’s arguments on the abolition of the Electoral College, and Ian Frazier’s piece in the New York Review which I read this morning strengthened my view. (I also realised this morning how mad the dating of New York Review issues is: it’s more than two weeks before the cover date and I’m reading a printed copy in Newcastle!)

4: Airline seatbelts are quite interesting.

5: A large survey of English adults conducted in May by researchers in Oxford found that “almost half think covid-19 may have been deliberately engineered by China against ‘the West’. Between a fifth and a quarter are ready to blame Jews, Muslims or Bill Gates, or to give credence to the idea that ‘the elite have created the virus in order to establish a one-world government’; 21 per cent believe – a little, moderately, a lot or definitely – that 5G is to blame, about the same number who think it is ‘an alien weapon to destroy humanity.’”

Once I’d recovered from the pain of that revelation, the same article delivered a good belly-laugh: “There’s a danger that in writing about QAnon – a social phenomenon not just in the US but in Britain, Germany and many other countries, and endorsed by a number of Republican candidates – you make it sound more interesting and mysterious than it is. It is interesting, but in the way hitting yourself in the face with a hammer is interesting: novel, painful and incredibly stupid.”

6: Channel 4 is seizing on US electoral chaos to advertise the availability of The West Wing on their streaming service, and even just seeing the trailers makes me feel a bit warm and fuzzy.

Disastrous data management, and a critically poor understanding of the relationship between population level data and individual clinical care, is one of the as-yet untold stories of the failure of covid-19 control in England. I hope we learn from that, and build upon those lessons to do everything Goldacre and co suggest.

8: Some of the best books of 2020 don’t actually exist.

9: Amazon has only just launched in Sweden. It didn’t go well, with the retail giant encountering problems both serious and trivial. “For reasons known only to Amazon itself, the Argentine rather than the Swedish flag was placed next to the word Sweden on the site’s country picker. Then there were the disastrous automatic translations that saw a cat-themed hairbrush described using the Swedish slang for ‘vagina’ (clearly the result of a direct translation of ‘pussy’), a children’s puzzle featuring yellow rapeseed flowers described as having a ‘sexual assault flower motif’, and football shirts labeled as ‘child sex attack shirt’.”

It all reminded me a little of this (which surely counts as pre-historic in internet terms).

11: Mass testing for covid-19 is now well underway in Liverpool, but questions remain about the effectiveness of the assessment of the pilot. “The Department of Health is being incredibly secretive about how this pilot is going to be evaluated. There’s a National Screening Committee which we’ve had in the UK for 20 years, and they’ve been sidelined from this. There’s a big concern that we’re not going to learn what we should because we don’t know what studies are being done alongside it, and the right scientists haven’t been involved … We still have public health teams who are underfunded to do track and trace, and people have been saying for six months that’s the way to control things on a national scale. There’s a cost effectiveness question here, and it’s not a case of mass testing or nothing. It’s this or some of the other alternatives.”

12: There was a time, not that long ago, when politicians disagreed civilly, and leaders clarified misconceptions about their opponents and worked to raise the tone of public discourse.

13: Paul Flynn’s interview with Sarah Jessica Parker in the latest Happy Reader made me reflect on the differences in our responses to Tony Soprano and Carrie Bradshaw, and contemplate the everyday sexism those responses perhaps reveal. As Parker and Flynn point out, why are Soprano’s murders downplayed and yet Bradshaw’s profligate spending on fashion overplayed in popular notions of those characters?

14: Once upon a time, computer mice with built-in telephones were a thing.

16: Reading about how dismissive rudeness was at least part of the underlying cause of the downfall of Lee Cain and Dominic Cummings. In some ways, it feels like a repeat of the same mistakes Fiona Hill and Nick Timothy were perceived to have made. Civility in seniority is perhaps an under-rated quality among those making the appointments.

17: In an order confirmation email, fashion and homeware retailer Next says “we are working incredibly hard to get your items to you.” They apparently underestimate my credulousness.

18: This book taught me that the Olympic torch relay is an entirely modern creation, a Nazi idea introduced for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

19: I find it hard to disagree that “the pandemic has brutally exposed a centre that has control over the country’s resources but does not know what’s happening on the ground.”

20: The Home Secretary has engaged in “forceful expression, including some occasions of shouting and swearing” which left some Civil Servants upset. The implication of the Prime Minister judging her not to have broken the Ministerial Code is that this was not “intimidating or insulting behaviour that makes an individual feel uncomfortable.” Which either means the Prime Minister doesn’t believe shouting and swearing to be intimidating or insulting, or that he doesn’t believe those who claim to have been upset, or that he doesn’t believe the Home Secretary engaged in the behaviour described. The Government’s statement isn’t clear on which of these is the case.

21: While pondering whether I should send an email at work today, I caught myself reflecting on Marcus Aurelius and Meditations. This is completely ridiculous, embarrassingly knobbish, surprisingly frequent and really quite helpful, all at the same time.

22: Some big wotsits were towed out of the Port of Tyne this afternoon. I assume they were bits of oil rigs, but don’t really know.

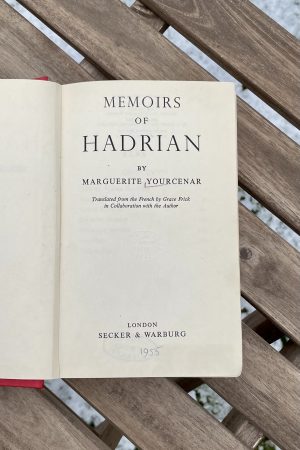

23: This book taught me the depressing word hemoclysm (coined by an American, so no ‘a’ or ‘æ’).

24: For a few years, while I was contributing to some guidelines, NICE used to invite me to their annual conference as a guest. One of the most memorable presentations in the years I attended was one on the extraordinary results of getting GPs to opportunistically remind older people not to sleep with their bedroom windows open: something that was commonly advised decades ago but which led to many older people sleeping in rooms which were unhealthily cold. A simple clarification in this DHSC campaign could have saved lives; I worry that the lack of one may do the opposite.

25: Twenty-six fire have broken out on buses in Rome this year alone. “The most dramatic incident occurred in the early hours of Saturday when an out-of-service bus burst into flames in the Aurelio neighbourhood. As the driver leapt to safety the heat melted the brakes, sending the bus rolling down a shopping street, torching six parked cars and four mopeds as it passed, causing a shop front to disintegrate in the heat and the windows of ground-floor apartments to explode. The bus, which was purchased seven years ago, eventually careered into a line of dustbins, setting them on fire as it slowed to a halt.”

26: I’ve never really thought about what happens to sailors when shipping companies collapse. It turns out it’s complicated and distressing.

27: I’ve never given a lot of thought to the logic of art restoration, but this article made me think about it. “Over a hundred years ago, the United States Army began looking into turning the Statue of Liberty back to her original copper color. ‘As might be expected, when the Statue of Liberty turned green people in positions of authority wondered what to do,’ writes Frazier. ‘In 1906, New York newspapers printed stories saying that the Statue was soon to be painted. The public did not like the idea.’ In the end, nothing was done. Change was accepted, and we let her green skin stay. And like a word moving through years, shifting its meaning, she continues to change, ever so slightly.”

28: It’s the first frost of the season, and the first day I’ve felt the need to don gloves for the walk to work.

29: This is a fantastic review of the human biological impact of space flight. In summary: it’s complicated.

30: Some people feel so strongly that face masks are unsafe that they scrawl messages on walls. I’m not sure what specific harms concern the author(s).

This post was filed under: Posts delayed by 12 months, Things I've learned.