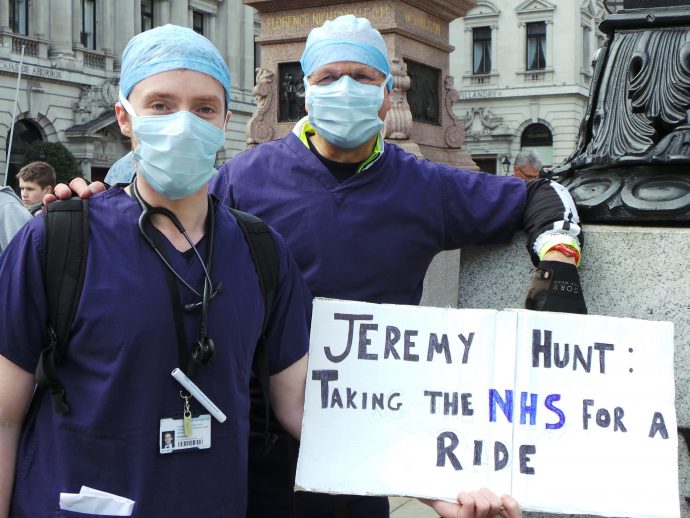

A number of politicians have recently made absurd statements about the role of the market and profit in healthcare, and specifically in the NHS. In political terms, the two worst culprits are the Labour Party and the National Health Action Party.

When the Labour Party left office in 2010, data1 showed that roughly 5% of NHS procedures were carried out in the private sector. Under the current Government, as of the most recent set of statistics, this is roughly 6%. It’s just worth bearing those proportions in mind whenever you hear Labour pontificate on the role of the private sector in the NHS. But I digress.

In his Party Conference speech, Andy Burnham asked:

And for how much longer, in this the century of the ageing society, will we allow a care system in England to be run as a race to the bottom, making profits off the backs of our most vulnerable?

I’ll answer that question in a moment. But to illustrate that Burnham is not alone, let us turn to the National Health Action Party.

You may not have heard of the National Health Action Party: it is a well-meaning but misguided Party whose platform—to defend and improve the NHS—is as vague as it is logically flawed. Dr Richard Taylor, co-leader of the party, was previously an MP; he signed an Early Day Motion in support of homeopathy, and praised the use of acupuncture and reflexology in cancer treatment. To date, the party has contested and lost nine elections2 with their best result being a 9.9% share of the vote for a single council seat in Liverpool. Again, I digress.

In The BMJ, in reaction to the news that Circle Health plans to withdraw from its contract to run the Hitchingbrooke Hospital in Cambridgeshire, a National Health Action Party representative said:

This perfectly illustrates the difference between the private sector, which seeks profits, and public NHS Trusts … This shows exactly why the market has no place in healthcare.

So, you ask me, what’s wrong with those quotes? They seem like perfectly sensible sentiments to me!

Both of these quotes are simply nonsense. Neither the Labour Party nor the National Health Action Party are campaigning for the removal of profits and the market from the NHS—and nor is anyone else.

Any modern business, be it a hospital or fishmonger, is reliant on suppliers who will draw a profit. The NHS doesn’t manufacture its own light bulbs and baths, nor generate it’s own electricity,3 so people will draw profit from supplying them.

Alright, you might be saying, but that’s not really medicine, is it?

But of course, profits are made on medicine too. Sure, the NHS could manufacture all the medicines it needs—it already manufactures some.4 But many medications are under patent. Are NHS patients to be prevented from accessing patented drugs? Of course not: so companies will draw a profit. And the more sick people there are, the bigger the profit there is to draw.

OK, you say, but medicines are a special case.

Except they’re not. Almost every product used to deliver healthcare—from syringes to catheters to implants to surgical tools—will generate a profit, as it is almost all bought in from commercial manufacturers.

Come now, you say, supplies are a red herring. I’m interested in healthcare—a human caring for another human. There’s no profit to be made there!

Oh, but there is. Management of human resources is a tricky business. Often, Trusts will hire in external experts to help with training, planning or management, many of whom will work for consultancies which make a tidy profit.

Everyone knows human resources officers aren’t human, you intone—though I couldn’t possibly comment, I’m talking about a nurse looking after a patient at the bedside. Where’s the profit in that?

The scenario you describe is just dripping with profit—from the agency that recruited the nurse, to the profit on the manufacture of his uniform, to the cut of his pay which goes to the nursing agency he’s working for, to the cut of his car parking fee which is given to the private company managing the facility.

Ugh. You do go on a bit. What’s your point?

Suggesting that the NHS be removed from the commercial market and freed from the pursuit of profit is nonsense. Of course, the internal market in which NHS providers compete with one another could be reformed or removed, but the NHS is involved in a wider external market which is here to stay. The NHS is one of the country’s biggest purchases of goods and services, and each supplier will be doing the best they can to—effectively—profit from the sick.

Even if, for the sake of a thought experiment, we say that the NHS could be isolated totally from the battle for private profit, the end result in terms of the health service alone might not be that different: there would be continual pressure to reduce costs to the taxpayer, which is effectively the same financial pressure as increasing profits to shareholders.

The true argument is about the extent of involvement of the private sector.

Consider privately-employed doctors. Would we trust doctors to the same extent if we knew their interests balanced our interests with profit potential? This isn’t something we have to treat as a thought experiment: most GPs are small businesses and work on exactly this principal with little discernable effect on levels of trust. But, again, it feels icky.

Consider private sector management of whole NHS hospitals. This might look like a step too far: it takes a layer of previously publicly-funded management, who perhaps tried to balance the drive for profits with the best interests of patients, and moves them to the profit-hungry private sector. Yet, the management would always be accountable to commissioners, who would be looking out for the patients: so does it really matter? Perhaps not from the conceptual standpoint—but I’ll admit that it makes me more than a bit uncomfortable. And while a sample size of 1 makes for a poor trial, the fact that the first hospital so-run has become the first hospital to be rated as “inadequate” on patient care does not feel reassuring.

Consider public health campaigns teaming up with well-known brands. Is it okay if public healthcare money inflates Aardman Animations’s bottom line, if using Aardman characters is a good way to get health messages to children? I’m not sure: evidence about cost-effectiveness could sway me one way or the other.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could have a debate on these issues that’s based in the real world, rather than the five-word soundbite world? Wouldn’t it be great if politicians would describe the extent of private involvement in the NHS that they believe to be appropriate, and we could then vote for the Party whose ideas most closely align with our own? Wouldn’t it be peachy if our politicians would stop patronising us all and treat us like adults?

As I said in my last post, the current model of delivery for the NHS is unsustainable. This is a problem that needs statesmanship, cross-party exploration, and—most importantly—tackling by adults.