What I’ve been reading this month

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

This was a novel charting the course of a marriage between a middle class African American man and woman in the contemporary United States. In particular, it covers the strain placed on that marriage after the man is wrongfully imprisoned. It is told in sections from the points of view of multiple characters.

The main themes were the gap between hopes and reality, the effect of incarceration on people’s lives and families, and the clash between traditional gender roles and those in modern society. The characters were well developed, believable, and entirely as irrational and frustrating as real people can often seem.

This was a slow and closely observed novel on a domestic scale. I found it absorbing and moving.

Stop Reading the News by Rolf Dobelli

This was book about the negative effects of engaging with the news, arguing that we should essentially disengage from daily consumption. I enjoyed this book and found the argument convincing, partly because I’ve been on a similar journey of late.

I would have preferred Dobelli to make the distinction between ‘news’ and ‘journalism’ a little earlier in the book, because I occasionally found myself arguing with his positions until I understood better that he was treating these as distinct entities. But, nonetheless, I found his perspectives throughout worthy of consideration.

Definitely a book I’d recommend, particularly in current times.

My Face for the World to See by Alfred Hayes

Originally published in 1958, this short novel was narrated by a troubled Hollywood screenwriter. In the novel’s opening, the screenwriter intervened to rescue an actress from the sea at a party, following what might have been an accident or might have been a suicide attempt.

The two almost accidentally fell into a relationship (an extramarital affair for the screenwriter) which took on a progressively darker air as their damaged selves came to the fore.

I found this intense and gripping. It had the concise and precise language of the classic American novels which worked well to heighten the tension.

Car Park Life by Gareth E Rees

This was a personal study of some of the hidden parts the UK’s retail car parks—not a topic that obviously required its own book, but a topic that turned out to be well worth reading about nevertheless.

Car Park Life was great, with exactly the right mix of wit, satire and underlying earnest. Rees mixed a beguiling and flowing combination of humour, psychology, sociology, autobiography and history around this unassuming topic.

This book has definitely changed my perspective on car parks!

A Study in Scarlet by Arthur Conan Doyle

I thought I’d read all of Sherlock Holmes as a teenager, and decided to re-read it in 2020. Having read this, though, I’m now pretty sure this is my first reading: I don’t remember any of the mormon-themed second part of this book.

Either way, I thoroughly enjoyed this first in the Sherlock Holmes series. There seems little point saying much more: you know what you’re getting into.

My Twentieth Century Evening and Other Small Breakthroughs by Kazuo Ishiguro

You can watch or read Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nobel lecture for free online, but I didn’t. I bought a small paperback copy which I read over a bowl of soup one lunchtime in Caffé Nero. That is possibly the most planetary resource intensive approach, and I should probably be ashamed… but I enjoyed it.

Ishiguro’s lecture described his lifelong development as a writer, underlined the importance of literature and made a plea for greater intellectual diversity in writing and the arts. I really like Ishiguro’s writing, so was predisposed to like this lecture. I suppose I probably wouldn’t have found it interesting if I didn’t find him interesting, so your mileage may vary!

Fleabag by Phoebe Waller-Bridge

I picked this up out of interest having enjoyed the TV series: this is the text of the original one-woman play.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading the play and also reflecting on the creative differences between the original text and the TV series. I also enjoyed the text on its own terms: Waller-Bridge has created a memorable and distinctive character.

On the other hand, much of the rest of the stuff in this volume felt like filler to me.

Reasons to Stay Alive by Matt Haig

This was a moving, eloquent and personal description of Matt Haig’s experiences with depression which I think helped me to better understand the subjective experience of mental illness.

There were some parts that felt less successful to me, though perhaps others appreciated them—I wasn’t particularly interested in others’ Twitter posts quoted in the book, for example—but I’m glad I picked this up nevertheless.

A Lover’s Discourse by Roland Barthes

Barthes built up a picture of the subjective experience of love through a series of “fragments”, descriptions of individual aspects of the experience drawn from literature or philosophy.

This was an astounding analytical work, in as much as it put into words emotions I’ve felt but never even considered classifying or really dwelt upon, but which certainly form part of being in love. Some of the ‘fragments’ felt like truly revelatory insights into my own life experiences.

On the other hand, if I’m being honest, most of this book was a bit of a slog to get through: it was a bit like reading a reference work of discrete entries. I read it piece by piece over several months because I couldn’t take it all in one go.

It was astounding and hard work to read at the same time.

Christmas with Dull People by Saki

It would probably have made more sense to read this in December, but it didn’t make its way to the top of the pile until this month.

Christmas with Dull People was a 48-page collection of four short, sharp stories satirising Edwardian social norms around Christmas. I don’t think I’ve read any Saki before and enjoyed his cutting wit. I enjoyed the last story, which concerned the writing of thank you letters, the most.

Motherland: Tortoise Quarterly, 2ed

Tortoise Quarterly is more magazine than book—it features thematic collections of longer articles from the Tortoise website.

In this edition, I particularly enjoyed Martin Samuel’s profile of Gary Linekar (who I previously knew almost nothing about), Zelda Perkins’s account of producing a musical with and for David Bowie, Susie Walker’s story of life as a female stand up comedian, and Simon Barnes’s deep dive into the causes of flooding in the UK.

Indistractable by Nir Eyal

It’s important context to know that Eyal is the author of another book on how to make technology addictive. He believes, and frequently argues, that such technologies should not be regulated because we can control our own usage of them.

In Indistractable, Eyal argued that one can maintaining focus despite potential distractions such as—but not limited to—addictive technology. He set out a few commonly described methods by which it is possible to maintain focus (such as planning to complete given tasks at given times). He also set out a few techniques commonly described techniques for reducing technology distractions (such as switching off notifications). He then set out a few commonly described tips on parenting in the age of modern technology (such as making sure children can use devices competently before allowing them unsupervised access). None of the ideas seemed original to me, and none added up to the thesis that these technologies should not be regulated.

Irritatingly, Eyal had a habit of presenting banal information as stunning insights. The most glaring of these was his repeated insistence that “total time spent on email = number of emails × average time spent on each email”. That is not an insight into anything, it is simply basic mathematics.

There was also a depressing assumption of affluence in Eyal’s writing. He suggested that we might encourage ourselves to go to the gym by bargaining with ourselves that if we failed to do so we’d burn a $100 bill. And he assumed an awful lot about availability of cash and time for parenting. All of which serves to undermine the thesis about regulation, which—after all—serves to protect the most vulnerable in society.

All in all, I found this pretty infuriating.

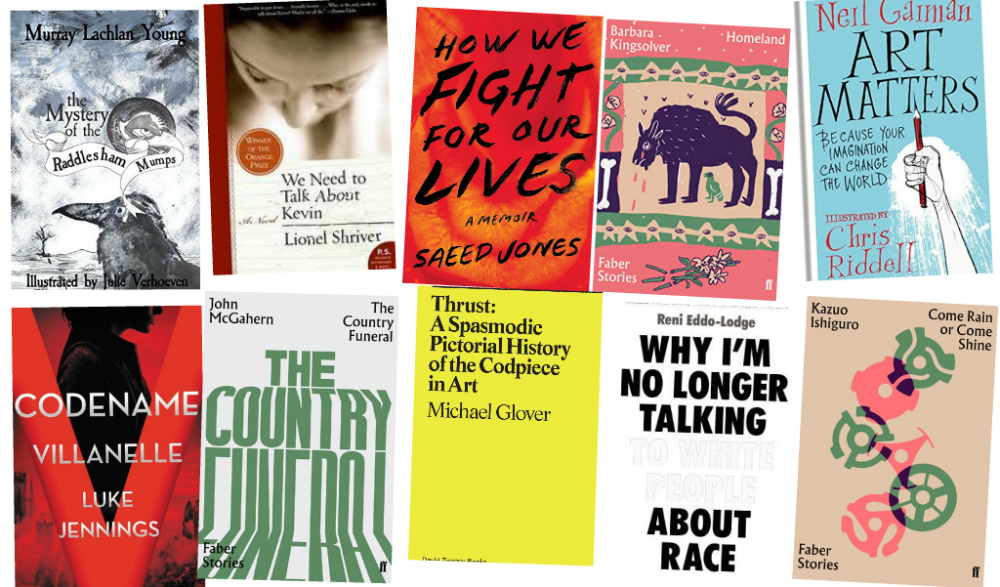

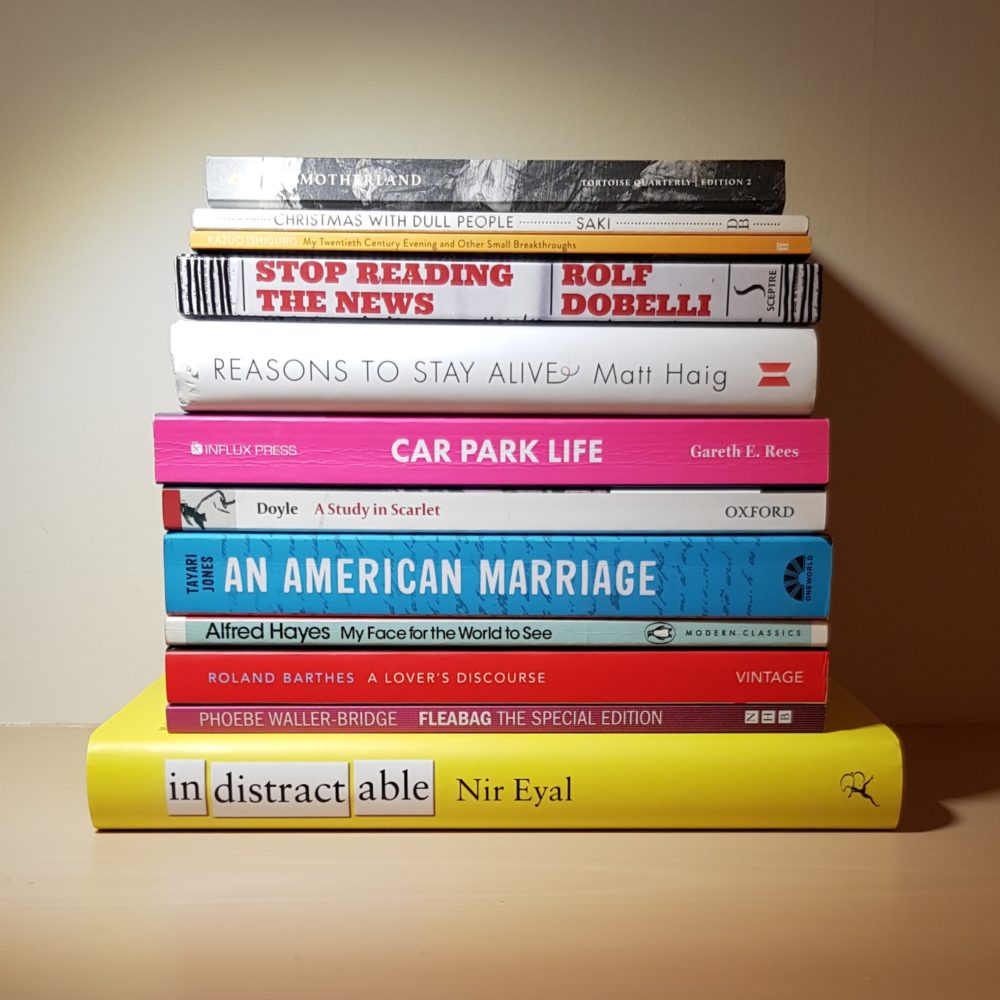

You might have noticed that this looks a little different to usual.

This is the 45th of these posts: they’ve appeared monthly since May 2016 and the formatting has been essentially unchanged since June 2016. This month, I’m playing with a new photography-heavy layout for 2020. I’m also experimenting with going back to publishing these towards the end of each month rather than at the start of a new month.

Both of these changes might be one-offs or might be permanent, largely depending on my whims this time next month.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Alfred Hayes, Arthur Conan Doyle, Books, David Bowie, Gareth E Rees, Gary Linekar, Kazuo Ishiguro, Martin Samuel, Matt Haig, Nir Eyal, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Roland Barthes, Rolf Dobelli, Saki, Sherlock Holmes, Simon Barnes, Susie Walker, Tayari Jones, Tortoise, Zelda Perkins.