31 things I learned in December 2020

1: The national lockdown unlocks tomorrow, so the time feels right for another deeply ill-advised prediction with potential to make me look like an idiot when you read this next year.

Here in Tier 3 country, the “great unlock” means that non-essential retail is to re-open. That is, people are going to be able to take public transport into their nearest city centre or shopping centre, and spend spend spend in poorly ventilated indoor spaces where the main control measures are stickers on floors. Indeed, Councils are planning to string up their regular Christmas lights to really draw in the crowds. This seems to be because it is assumed that the transmission risk associated with retail remains consistent even during winter weather and with Christmas crowds, which seems deeply unlikely to me.

On top of that, the Government is lifting lockdown at a point where the country is still seeing more than 14,000 new covid cases per day, which means we have a large pool of people ready to act as sources of infection: the 14,000 only counts confirmed infection, there will be many additional people each day with undetected infection because they are asymptomatic or choose not to be tested.

It’s hard to see any outcome other than case numbers bouncing up rapidly over the next three weeks: and with case numbers getting towards / as high as / even higher than the numbers immediately before the latest lockdown, it’s hard to see how the planned lifting of restrictions over Christmas can possibly go ahead… but it’s also impossible to see how, politically, this is something on which the Government can reverse ferret.

Even without the lockdown and tiering decisions, the Government boxing themselves into a decision a month ahead of time looks crazy to me: it may have been more prudent to announce conditional principles backed up by work with retailers and the travel sector to guarantee refunds for cancelled travel plans if the relaxation can’t proceed.

Though, perhaps with a larger dose of optimism than realism, Wendy’s Christmas flights to Northern Ireland are already booked.

2: From this book, I learned that it was only in 1938 that an Act of Parliament required every local authority to provide a fire service. If you’d asked me to guess, I’d probably have said it became a requirement after the Great Fire of London, putting me about three centuries out

3: Instagram has had a big impact on the design of luxury watches.

4: One can now take music grade exams, up to grade five, in DJing.

7: The first autopsy in the New World occurred in 1533 “when the Catholic Church ordered an autopsy on the conjoined infant twins Joana and Melchiora, who had died eight days after birth. The goal was to determine if the children shared a soul; the priest baptized them both separately as a matter of precaution as he was not sure whether they represented two bodies and two souls or only one.” The conclusion? Two.

8: The vaccination programme has begun.

10: I never previously realised that octopuses are so interesting. And they have beaks!

11: The Prime Minister who, a year ago, offered the electorate an “absolute guarantee” of securing a trade deal with the European Union by the end of 2020 says it is “very, very likely” that he will break his promise. Even if we ignore the bluster and accept that it’s pretty likely that a deal will be done in the end, it’s hard not to see this posturing as deeply damaging to trust in politics.

12: Dominic Cummings is a joke.

13: How to escape from Titanic.

14: It didn’t have to be this bad.

15: I’ve never before clocked the (obvious) fact that bone china isn’t vegan or vegetarian friendly. I wonder if there’s a vegan crockery alternative to William Edwards for First Class passengers on British Airways?

16: On my rainy walk to work this morning, a group of 12- or 13-year-old boys ran past me with their teachers (or perhaps coaches) riding bikes alongside. As the stragglers slowed to a walk, one of the faster kids aggressively shouted, “Come on you lazy bastards, get moving!” Something about this scene jarred with me, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on what.

I think it may be something to do with rarely hearing this sort of hectoring in everyday life. Had I been one of the stragglers at that age—quite likely, if I hadn’t found an excuse to get out of running in the first place—this would have been the least effective strategy to get me moving faster, and perhaps the most likely to make me roll my eyes and snigger.

It also made me wonder whose behaviour the shouty child was modelling. Perhaps it’s a sports thing. I’ve chaired three outbreak control team meetings for elite sports teams in the past week, and I don’t think I’ve felt as culturally out of my depth since working at the Department of Health around Glyndebourne time.

17: If you asked me to name words that typically follow “agile” then “lighthouse” would not previously have featured among my answers. Yet the phrase “agile lighthouse” has been crowbarred into my vocabulary by people involved in the covid response who seem to speak a different version of English to me, and searching online reveals that it is genuine management speak.

18: It’s hard to disagree with Dominic Cummings’s assessment that “Issues of existential importance are largely ignored and our political systems incentivise politicians to focus more on Twitter and gossip-column stories about their dogs.”

It’s equally hard to ignore the profound pathos of that statement given that less than a year ago, he was hubristically describing the Government as having “a significant majority and little need to worry about short-term unpopularity.”

Cummings is possibly the only man in Britain who needed to spend time in Government to appreciate that people who dedicated their lives to winning regular public popularity contests are people who dislike being disliked—and Alexander “Boris” de Pfeffel Johnson dislikes it more than most. It’s hard to conceive a more fundamental misjudgement of character than assuming this Prime Minister to be one who wouldn’t worry about short-term unpopularity in pursuit of more noble goals.

19: With the number of new confirmed covid-19 cases in the UK each day now similar to that at the introduction of the November lockdown, the planned lifting of restrictions over Christmas is cancelled. But, please guv’, it’s nothing to do with the Government’s decision-making, it’s all to do with a new variant of the virus.

20: In quite possibly the most bizarre bit of Government messaging to date, the Secretary of State for Health is urging everyone to “act like they have the virus” while imploring them to continue attending school, workplaces (if they can’t work remotely), take outdoor exercise in public spaces, visit essential retailers, and more besides—all of which are not allowed nor remotely sensible for people who have covid. Marr really ought to have asked, “Would you be sitting here in my studio if you had the virus?”

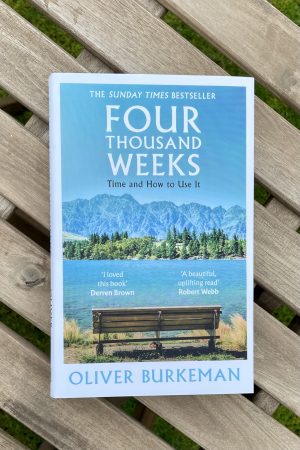

21: Napoleon, it is claimed, “directed Bourrienne to leave all letters unopened for three weeks, and then observed with satisfaction how large a part of the correspondence had thus disposed of itself and no longer required an answer.”

22: “The government has consistently throughout this year been ahead of the curve in terms of proactive measures with regards to coronavirus.” I’m not sure to which curve the Home Secretary refers; presumably not the curve which, to date, shows that more than twice as many UK residents have died of or with covid-19 than voted for her at the last election.

23: There are seven kinds of gift… or maybe more.

24: “In the 1960s, NASA went to huge expense to contain possible pathogens from the Moon” but the measures were so disastrously poor that the effort would have had little effect. This is a great story: particular highlights are the choice to base control measures on spread of Yersinia pestis and that “NASA’s plans stipulated that quarantine at the LRL could be broken in the event of a medical emergency. Ironically, if a lunar microbe made an astronaut really sick, that astronaut would be removed from quarantine.”

25: “Even on the darkest nights there is hope in the new dawn.”

26: I’m currently really enjoying The Heart’s Invisible Furies. The novel (at least as far as I’ve read) has vignettes from Cyril Avery’s life aged 7, 14, 21 and so on, every seven years. This has made Wendy and me reflect on how this structure would reflect our own lives: both of us have collected five vignettes so far; each vignette would see us living in a different house, each at a different school or workplace. We’d both have few recurring characters outside family—though we’ve been together for the most recent three vignettes of each other’s stories.

27: “If you tell Facebook not to collect location information from your iPhone, then it doesn’t, right? Wrong.” The fact that Facebook collects oodles of data on users is hardly news, but now and again, something like this pops up and it feels so egregious that it almost lends credibility to the conspiracy theorists.

28: There’s a direct line of succession from the Acorn processor in the BBC Micro which sat in the corner at school to the ARM (Acorn RISC Machine) processor in the iPhone I’m typing this on.

29: The iOS Reminders app has got much more fully featured since I last used it (around iOS 5).

30: A Government which claims to be keen on parliamentary sovereignty is ramming legislation through without time for proper parliamentary scrutiny and then shutting the doors on the House of Commons for an extra week. Her Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition is supporting the Government in implementing legislation it disagrees with, because it is unable to figure out a better approach. And in the world of 2020, all of this feels like par for the (lamentable) course.

31: At the stroke of 11pm, the Government’s actions stripped me of more freedoms and opportunities than at any other moment in my life so far.

Instead of having free pick of the job market across 28 countries, I’m limited to one. Instead of having the automatic right to live in any of 28 countries, I’m limited to one. No longer can I travel at will or whim across Europe; and no longer will I be guaranteed a lack of roaming charges.

Brexit is regrettable for much bigger reasons than those that affect me directly—not least friends born in other EU countries who have dedicated their lives to the NHS now being made to feel like second-class citizens (if even ‘citizens’ at all)—but when Government rhetoric is all about victory and celebration, it feels like tonight’s a night for self-indulgent melancholy.

This post was filed under: Posts delayed by 12 months, Things I've learned.