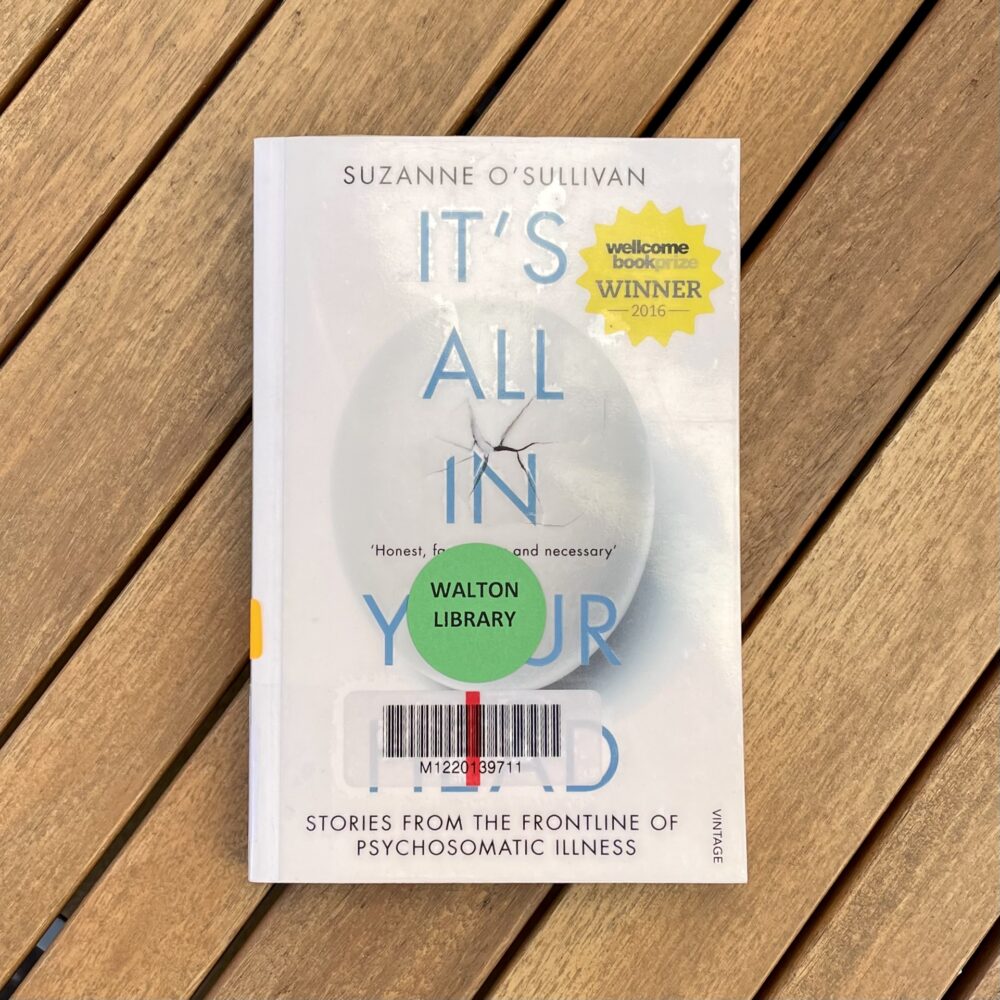

I’ve been reading ‘It’s All in Your Head’ by Suzanne O’Sullivan

Published in 2015, this was Suzanne O’Sullivan’s first book, and it’s the first of her books that I’ve read. I was motivated to seek a copy after seeing excellent reviews of all of her books.

O’Sullivan is a neurologist, and in this book she discusses patients she has seen with psychosomatic neurological presentations, such as seizures, paralysis, and—in one particularly memorable case—blindness. Based on my experience, O’Sullivan is right to say that psychosomatic illness is not discussed in any great length during medical training. I took a lot away from this book as a result. In particular, it is always useful to be reminded that psychosomatic illnesses are no more under the patient’s control than those with organic causes.

The book is beautifully written, and I found O’Sullivan’s deep reflections on her practice and her uncertainties especially valuable.

Some quotes that I particularly liked:

Modern society likes the idea that we can think ourselves better. When we are unwell, we tell ourselves that if we adopt a positive mental attitude, we will have a better chance of recovery. I am sure that is correct. But society has not fully woken up to the frequency with which people do the opposite – unconsciously think themselves ill.

If you take one hundred healthy people and subject them to the exact same injury you will get a hundred different responses. That is why medicine is an art.

Anger has a purpose. It tells others we are not alright. It also has a lot in common with psychosomatic symptoms. It can be misleading because often it is something else in disguise – hurt or fear repackaged. It is easily misinterpreted, both by those who feel the anger and those at the receiving end. And its effect may be detrimental. It is frightening. The person at whom the anger is directed may well be compelled to flee, possibly just when they are most needed. Anger can destroy the relationship between patient and doctor. The doctor escapes or avoids or ends up treating the anger and not the patient.

There is a terribly delicate balance in the investigation of benign-sounding symptoms. One must investigate to rule out a physical cause if it seems necessary, but the line where investigations should be stopped is drawn very faintly. Primum non nocere. First, do no harm. If you investigate and find something incidental, what do you do? And when do you say no more tests?

Laughter is the ultimate psychosomatic symptom. It is such a normal part of the human experience that all its facets are universally accepted. Now all we have to do is take the few short steps to a new realisation. If we can collapse with laughter, is it not just as possible that the body can do even more extraordinary things when faced with even more extraordinary triggers?

I look forward to reading more of O’Sullivan’s books—especially her most recent one, The Sleeping Beauties, about mass hysteria events, as this crosses neatly with my professional interest in public health.

Thanks to Newcastle University Library for lending me a copy.

This post was filed under: Health, Post-a-day 2023, What I've Been Reading, Suzanne O’Sullivan.