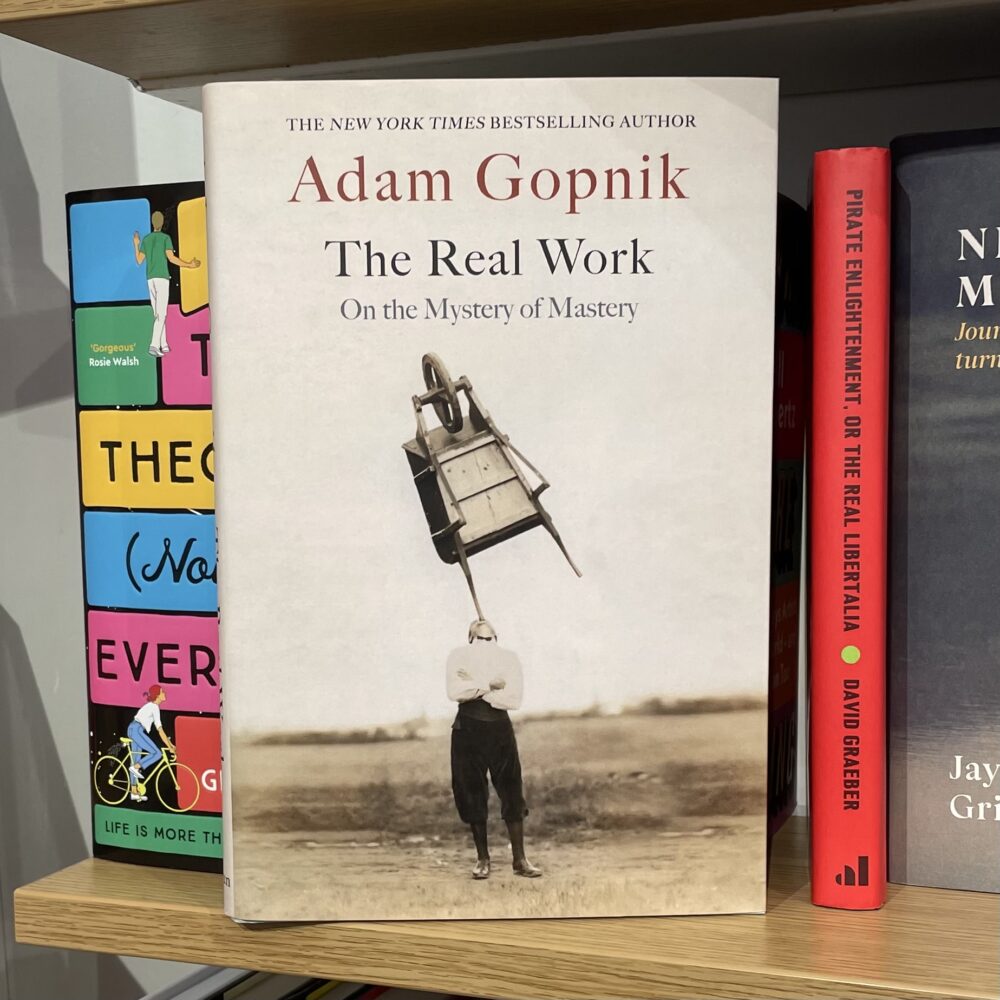

I’ve been reading ‘The Real Work’ by Adam Gopnik

The subtitle, ‘The Mystery of Mastery,’ would have been much the better title for this reflection on mastery, but there isn’t much else that I’d change about this book.

I know of the American writer Adam Gopnik from his many non-fiction essays, his byline being one that always guarantees an interesting read, no matter how esoteric the subject. He has published many books, but this is the first I’ve read. I was inspired to read it after seeing an FT review by Erica Wagner.

Gopnik tries to understand what it takes to master skills in a variety of fields, sometimes by simply spending time with masters, and sometimes by attempting to learn the skill himself: be it magic, dancing, bakery, painting, boxing, urinating (he suffers paruresis) or driving. He reflects philosophically on the similarities in mastery between fields, while keeping the tone light.

Gopnik’s observation that mastery is much more common than we realise is perhaps the one that will stick with me longest from this book. There are people all around us—including ourselves—who are exceptionally skilled in various ways, but that don’t necessarily recognise that description even of themselves.

I was also taken by Gopnik’s observation that mastery of magic has very little to do with the technique of illusion—which is sometimes elementary—and much more with the patter and performance around it. I also enjoyed his reflections on the similarities between ballroom dancing and boxing, which would never have occurred to me until they were pointed out.

Like all good books, though, this is actually about a huge number of other topics, from Gopnik’s relationship with his aging parents, to the nature of life, and to his relationship with his children.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book, and it provided much food for thought.

Some quotations I noted down:

By now, you have heard the rumor: the hummingbird and the whale have the same number of heartbeats in a lifetime, differently expended. In that truth we seek some consolation for the speed of our mortality. Each being has a heart that beats a billion times—one over months, the other over decades. The hummingbird lives a brief and busy life, its heart beating literally a thousand times a minute, and the whale a slow and ponderous existence out in the deep. Yet their inner experience, the heartbeat rhythm of their lives, is foundationally alike. The hummingbird would not trade its place for the whale’s, because the hummingbird’s life is the whale’s, in a decent existential translation.

More than we fear being evil, or even outrageous, what we fear most in life is being embarrassed. It is the great constraint, and the great propellant, of human accomplishment, and of its opposite, human destructiveness. Much of the worst of history is only comprehensible as a tale of embarrassment feared and, at huge lengths, avoided, or trying to be avoided.

The highlights of life are first unbelievably intense and then absurdly commonplace.

Studying snowflakes, we were once told that they were all different, and thus gave some kind of natural metaphoric endorsement to our inherent individuality. Instead, it turns out that snowflakes are all alike, when they begin in clouds, changing in form and appearance only as they drift to earth through the accidents of wind and weather. A better image, that, of how we truly live and differentiate ourselves.

People were fooled because they were looking, as we always seem to do, for the elegant and instant solution to a problem, even when the cynical and ugly and incremental one is right.

If the concert audience is baffled, they are intrigued, even impressed. In show business, if they are baffled, they leave. In our age, the difference between entertainment and art is that in entertainment we expect to do all the work for the audience, while in art we expect the audience to do all the work for us.

My mother continued baking and cooking even as she aged, and though some of it was at her usual level, a habit of habit crept in and then triumphed. She worked, this woman whose ease in the fine art of strudel-rolling was my very first memory in life of mastery, increasingly intently, increasingly angrily—if one can imagine an enraged croissant or a pain au chocolat baked in fury—increasingly made for its own frightened sake. I can still do this. I can. On that much smaller scale, my mother’s baking became, as the years went by and our visits became first more infrequent (it was exhausting to go) and then more frequent (they needed more care), baking for the sake of the bagel. The bagel eaters were left outside the circle of dough.

But, and this is a truth that must be said, over and over: suffering is intrinsic to the human condition, and so we cannot grade it on any kind of absolute scale. What we feel is what we feel, and though it may be true that we cry when we have no shoes until we meet a man with no feet, the larger truth is that having no shoes is our only way of beginning to understand what it must feel like to have no feet. Deprivation, discomfort, unhappiness—these cannot be wished away by pointing to those who have better reason for them than we do. If we could be cured by the truth that someone is suffering more, then human suffering would long ago have been cured.

We have to pack our own parachutes with the silk that we have gathered and tested, probing it for each possible moth hole and tear… but then you have to jump out of the plane.

We must imagine Sisyphus happy. Because while the only kind of action we can attempt may be illusory, a stone rolled up a hill only to roll down again, the happiness it gives us is not. Sisyphus is right to be happy with his work. It’s what he’s got. It’s what we have. In a doomed, fatal, mortal world, we are all Sisyphus rolling stones, but we are also aware of the possibility of contentment as we do, not because the stone won’t roll back (eventually, it will), but because when it does—and this is the secret, hopeful side to the curse that the gods gave Sisyphus—it doesn’t actually crush us. It just gives us the work to do again.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, What I've Been Reading, Adam Gopnik.