Easy peasy

I’m not sure what could possibly have reminded me of it, but I’ve thoroughly enjoyed re-listening to this classic album.

This post was filed under: News and Comment, Politics, Post-a-day 2023.

I’m not sure what could possibly have reminded me of it, but I’ve thoroughly enjoyed re-listening to this classic album.

This post was filed under: News and Comment, Politics, Post-a-day 2023.

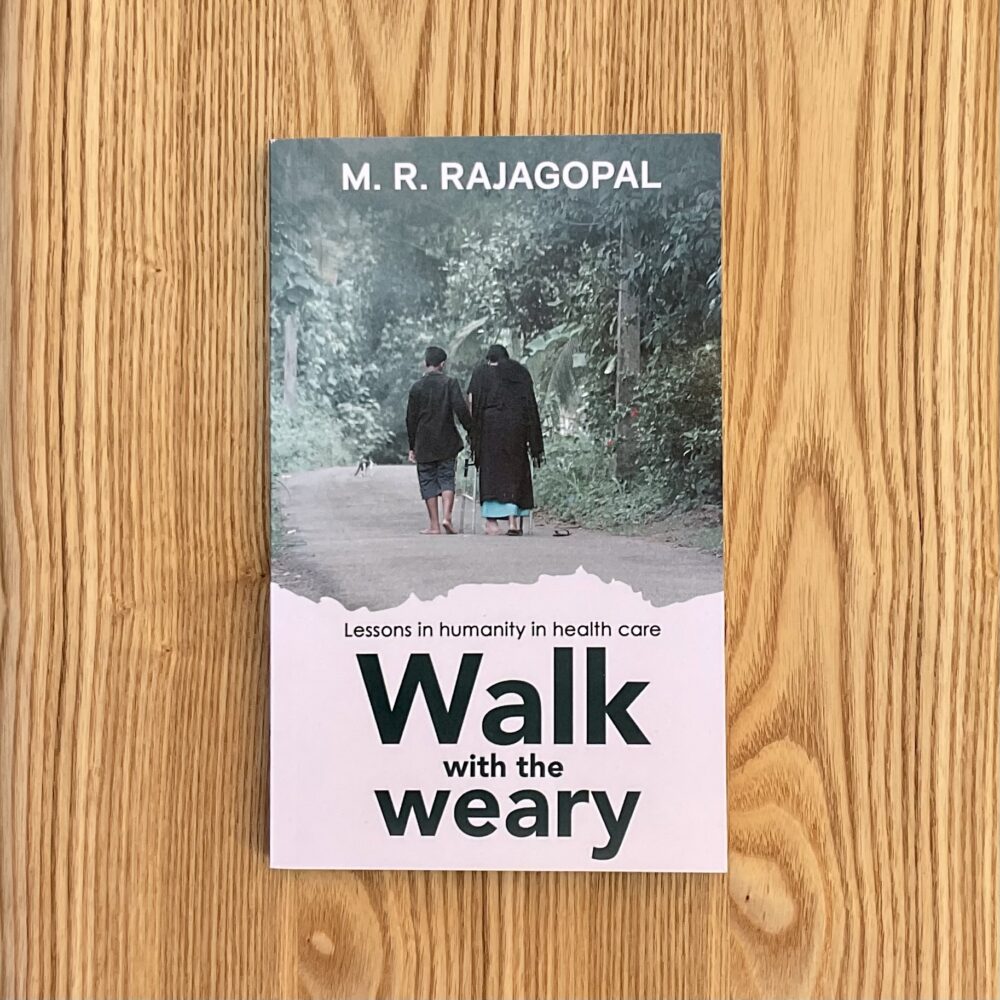

This 2022 book by the noted palliative care physician from Kerala in India was highly praised by my Goodreads friend Richard Smith, and sounded like a book which would be up my street. I found it somewhat hard to get hold of a copy, but eventually tracked on down online.

I very much hope that this book becomes more widely available because Rajagopal gives some clear and important messages. His writing considers the limits of medicine, its potential to do net harm by focusing more on diseases than patients, and the fundamental importance of holistic care. While entirely different in tone, the messages reminded me a little of Ivan Illich’s Limits to Medicine.

Rajagopal was a pioneer of palliative care in India, and that aspect of this book was also fascinating. He tells us his story, from first recognising a substantial lacuna in the care of patients (a lack of proper pain management) to building a coalition of likeminded colleagues to ultimately transforming medical practice. This aspect of the book reminded me of Misbehaving by Richard Thaler, his account of how he transformed the field of economics by integrating human behaviour. In some ways, Walk with the Weary is an account of how Rajagopal transformed the field of medicine, especially in India, by integrating human compassion.

Rajagopal’s view is that palliative care ought not to be restricted to those who are dying, but that it should be there for ‘all illness-related suffering.’ I had never conceived of palliative care in that way before, but found the argument inspiring. It encapsulates something important about how medicine is best practised.

One of my regrets about the way public health is practised in the UK is the siloed nature of the work. I work in health protection and mostly deal with the acute response to cases of significant infectious diseases. Often, the people who are suffering with these diseases have myriad other needs, but there is no overall coordinating ‘sorter of problems’ to tackle that. I found Rajagopal’s account of overcoming broadly similar structural barriers in his work inspiring.

Some notable quotations I took away from this book:

Imagine a researcher, a few centuries from now, going through the history of ‘Modern Medicine.’ What would her verdict be on healthcare in the early twenty-first century? What would she feel about the healthcare system in which, despite all the accumulated medical knowledge, 80% of the world continues not to have access to basic pain relief? Would she not ask herself—how could they be so senseless to invest so much time, energy, and money in research on ‘conquering’ diseases but not focus on channelling that knowledge so as to provide relief to those in suffering?

No therapeutic scan has yet been created that can measure happiness. There is no medical intervention yet that can generate joy, but the love that I give and the love I receive may be able to do that. If I am made physically comfortable within reasonable limits, this love could well be the only thing that matters as death approaches.

The world over, pain seems to be poorly understood and taught. Diseases are given importance; pain or suffering is ignored.

Many people, including many medical and nursing professionals in India, fail to realise the depth and nature of pain. It can be beyond the average person’s imagination. If severe, it affects your personality and changes you from a sociable human being to a selfish being, caring about nothing other than one’s own pain. It fills the mind space, leaving no space for rational decision-making.

This change in behaviour is immediate when a sudden, agonising pain occurs, but generally resolves completely when the pain is relieved. Sadly, and more tragically, long-term pain, such as low back pain, often irrevocably changes a person. The person may manage to put on a normal front to the world at large, but once back in the privacy of his or her own home, the façade crumbles. The irritability surprises, others; and at some point, it wrecks relationships – between spouses, between parents and children, and eventually with colleagues too.

There was a lot of food for thought in this book.

This post was filed under: Health, Post-a-day 2023, What I've Been Reading, MR Rajagopal.

In the great, over-stuffed pantheon of things I know nothing about, football looms large. It’s a subject on which I’m not even casually conversant, I’m less well-informed than your average six-year-old. It’s only two years since I was stunned to learn that Aston Villa wasn’t a London team.

And yet, I know that the Carabao Cup Final is this afternoon.

I couldn’t explain what the Carabao Cup is, nor pick it out of a line-up, nor explain why it’s named after a buffalo, but there’s still no fooling me: a big match is happening today.

I know this because I live in Newcastle, and I know of no other city where the football club and the city are so closely enmeshed. It’s partly to do with the location of the stadium right in the city centre, which means that the cheers after a goal resonate through the streets. But it’s also something that’s deep within the psyche of the city.

And so, I know it’s the Carabao Cup Final because the city is festooned with black-and-white bunting. The team’s flag has replaced the city flag outside the Civic Centre. Estate agents have turfed every property out of their window to dedicate their entire displays to supporting the club. Even a local care home has decorated their garden with black-and-white ribbons and balloons.

The talk in my office—where, incidentally, roughly 90% of the staff are female—has not been about whether anyone is making the trip to Wembley, but about who is making the trip. Jokes about silverware and absent goalkeepers are ten a penny.

Most shops and businesses in the city are closing early today to release staff to watch the match, as my friendly Caffe Nero barista had the foresight to tell me last Sunday. It’s a citywide bank holiday in all but statute.

And so: I might not be able to name a single Newcastle player and I couldn’t even tell you with certainty who the opposing team is, but I know it’s the Carabao Cup Final today. I hope Newcastle does well.

This post was filed under: News and Comment, Post-a-day 2023, Football, Newcastle upon Tyne.

For the uninitiated, Emily in Paris is a sublimely mindless Netflix comedy series about a young marketing professional who relocates from Chicago to Paris. Its third series was released on Netflix recently. Wendy and I have enjoyed all three series enormously.

There’s much to dislike—offensive cultural stereotypes, casual consequence-less use of tobacco products, the two-dimensional characters. Yet, it is beautifully shot, is filled with absurdly couture fashion worn by characters without a hope of affording or storing it, and the whole series exudes charm and baseless optimism. Wendy sometimes mentions the value of programmes “where nothing bad ever happens,” and I think this fits that bill.

The writing is ropey throughout: by the third series, plots are telegraphed so far in advance that Wendy and I would occasionally forget whether something had happened or was going to happen.

But Emily in Paris is gentle and comforting in the way that only properly mindless TV can be.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, TV, Netflix.

‘Faith and Science’ is a small exhibit which forms part of Sunderland Art Gallery’s permanent collection. It gathers works by contemporary glass artists which represent aspects of, well, faith and science.

I very nearly walked straight past this—it’s positioned very close to the door—but two works caught my eye.

This remarkably prescient 2018 sculptural triptych by Luke Jerram illustrates the electron micrographic appearance of smallpox, HIV and an “untitled future mutation” with a more-than-passing resemblance to COVID-19.

In his statement, Jerram asks, “Has this virus been created in the laboratory or evolved naturally?”

Jerram is perhaps better known for his giant sculptures of the moon and the Earth (the latter currently floating in a dock at Canary Wharf)—who knew that he also basically predicted the pandemic?! He has also since made artworks of both the COVID-19 virus and one of the vaccines.

This 2005 triptych by Katharine Dowson demonstrating mitosis also caught my eye. Interestingly enough, Dowson has also created work inspired by vaccines: in her case, A Window to a Future of an HIV Vaccine.

This post was filed under: Art, Post-a-day 2023, Katharine Dowson, Luke Jerram, Sunderland, Sunderland Art Gallery.

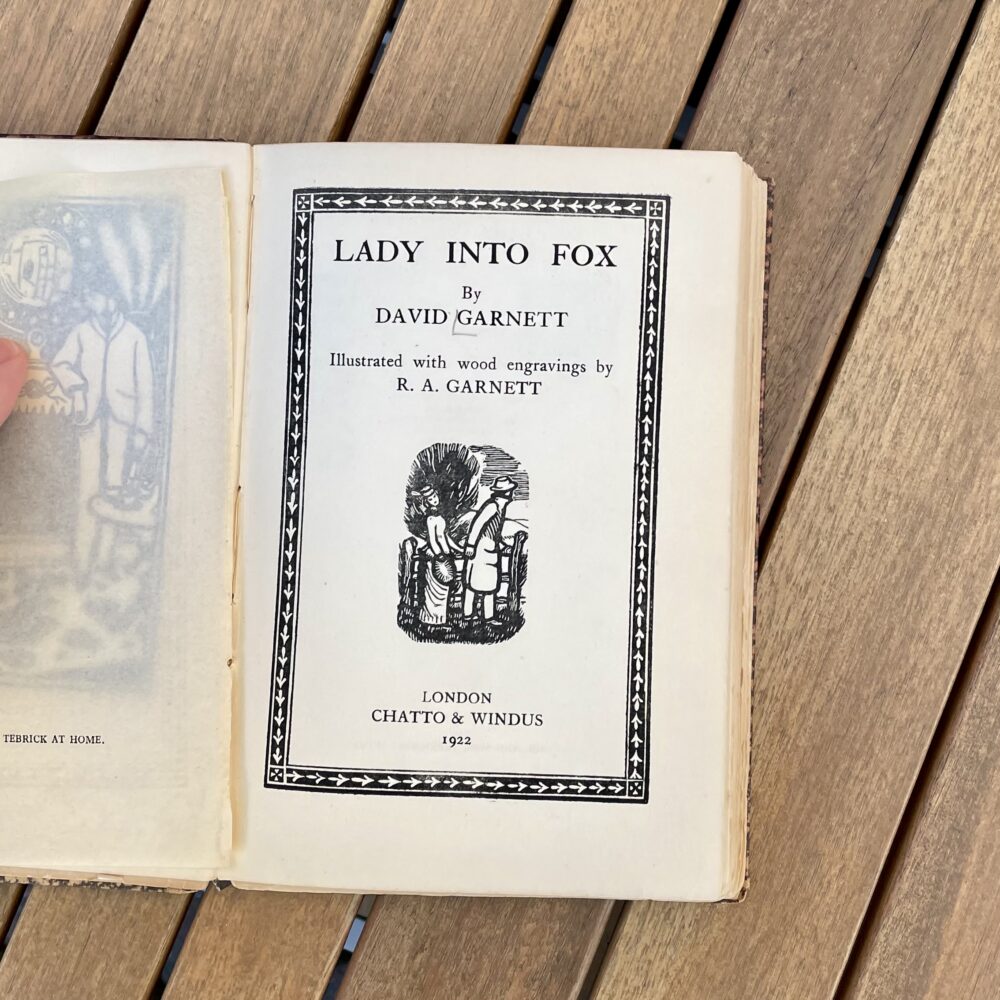

This is an odd little 1922 novella in which the central character’s wife is mysteriously transformed into a fox. They initially continue almost as if nothing has happened, the vixen wearing clothes and sitting at the table to eat.

Over time, her vulpine nature overtakes her human tendencies. The couple drift apart as she moves into a den, though maintain a close affection.

I enjoyed this mostly as a brief curiosity.

A couple of quotations:

Wonderful or supernatural events are not so uncommon, rather they are irregular in their incidence. Thus there may be not one marvel to speak of in a century, and then often enough comes a plentiful crop of them; monsters of all sorts swarm suddenly upon the earth, comets blaze in the sky, eclipses frighten nature, meteors fall in rain, while mermaids and sirens beguile, and sea-serpents engulf every passing ship, and terrible cataclysms beset humanity.

This story was made up by his neighbours not because they were fanciful or wanted to deceive, but like most tittle-tattle to fill a gap, as few like to confess ignorance, and if people are asked about such or such a man they must have something to say, or they suffer in everybody’s opinion, are set down as dull or “out of the swim.”

My thanks to the London Library for lending me a beautiful 1922 edition of this book with the original woodcuts by Garnett’s then wife—even though the book is dedicated to Duncan Grant, with whom he’d had an affair. Life was complicated among the Bloomsbury set.

Some people speculate that the novel is about the affair with Grant; others that it’s about the relationship with his wife. Both strike me as perfectly plausible, but then so does virtually every other interpretation, including the idea that it’s just a fantasy story with no allegorical meaning whatsoever.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, What I've Been Reading, David Garnett.

The gradual shift towards springtime, which means I’m walking to work in the early light rather than the pitch dark, is richly welcome.

This post was filed under: Photos, Post-a-day 2023, Newcastle upon Tyne.

‘Black Britain’ was originally—in much rougher form—a blog created by Jhanee Wilkins, a photographer from the West Midland. It’s now an exhibition at the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art.

The exhibition has a simple, repeating structure. Each series begins with an A4 page of text in which a black person introduces themselves and their experience of racism while growing up and living in Britain. This is followed by a photograph of them looking directly at the camera, one of them looking elsewhere, and a third of an object from their lives.

There is something deeply affecting about staring directly into the eyes of a person immediately after reading about their experience of racism. I was moved by the experience of Kae, born in Wolverhampton, who says,

I do not feel represented in this country, I do not feel welcome even after 42 years.

I can only begin to imagine, and certainly can’t fully appreciate, how fundamentally destabilising it must be to feel unwelcome in the country where you were born and have lived your whole life.

I was struck in a complete different way by Anne Marie’s story:

I think mainly, in the workplace that’s where I find that it is awkward for me to completely be myself. If I would like to bring my own food into work to heat up in the staff room, there’s a whole load of questions about what I’m heating up or the smell of it.

This reminded me of how privileged I am to not have to live with self-consciousness about this sort of thing, and to be able to go through life barely giving it a second thought.

‘Black Britain’ continues at the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art until 16 April.

This post was filed under: Art, Post-a-day 2023, Travel, Jhanee Wilkins, Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sunderland.

When I was seven years old, I distinctly remember believing that talc was the hardest substance on Earth. I obviously knew that talcum powder felt soft, but convinced myself that the individual bits of talc must be really, really hard.

I reached this conclusion after reading that talc was ‘number one’ on the Mohs hardness scale. Because this was referenced essentially in isolation, I understood ‘number one’ on a ‘hardness scale’ to mean ‘hardest.’ Obviously, I now know that it’s the softest mineral on a 10-point scale.

I’ve been ruminating on this over the past few days: my problem was essentially misinterpreting language as a result of not understanding the wider context. This is also a danger with language prediction models like ChatGPT: they too have ingested a load of text and are—in essence—quoting it back at people, while making basic statistical inferences along the way.

What these models try to do is simply predict the next word, based on statistical analysis of lots of prior text. They are a better-trained cousin of predictive text on your phone; they are not HAL 9000. They don’t have any understanding or general intelligence.

Exposing ChatGPT’s lack of understanding is trivial. For example, from my own messing about:

Which is taller: a 100cm giraffe or a 1m mouse?

A 100cm giraffe is taller than a 1m mouse. Giraffes are known for their long necks and are among the tallest mammals in the world, with adult males growing to an average height of about 5.5 to 6 meters (18 to 20 feet). In comparison, the average height of a mouse is much smaller, usually around 10 to 20 cm (4 to 8 inches).

So, a 100cm giraffe would certainly be taller than a 1m mouse!

And also this:

Would it cost more to buy 6 £1 eggs from Waitrose or Aldi?

As of my knowledge cut off in 2021, the cost of eggs can vary between different stores.

However, Aldi is known for offering lower prices on a wide range of products, including groceries, compared to more premium stores like Waitrose.

So, it is likely that it would cost less to buy 6 £1 eggs from Aldi than from Waitrose.

And also this:

What is hotter: a drawing of an ice cube, which is kept in the freezer, or a drawing of the sun, which is baking in an oven?

Even though both the drawing of an ice cube and the drawing of the sun are subjected to different environmental conditions, such as being kept in a freezer or being baked in an oven, they still cannot be described as hot or cold as they are just illustrations and do not have physical temperatures.

And also like this:

How many times does ‘times’ appear in this question?

The word ‘times’ appears only once in the question you just asked.

People like asking ChatGPT to write emails and speeches, and are impressed with results that are—at heart—just tweaked combined quotes from a wealth of written material. That’s fine, and those responses might well be impressively useful: ChatGPT has read many more Best Man speeches than any of us ever will, so has a better idea of what word ought to come next.

However, people can easily be fooled by these responses into assigning ChatGPT human-like intelligence. This might lead them to ask models like this to undertake real-world high-risk tasks without appropriate supervision. My background means that I automatically worry about their use in medicine. Some of these uses are obvious, like providing basic medical advice, and ChatGPT in particular has some safeguards around this.

Others are not obvious: people asking these models to summarise long medical documents, or to distil patient histories into problem lists. These are problematic because they lie on the border between ‘text analysis’—at which these models excel—and ‘real-world interpretation,’ at which they comprehensively suck, but can have a sheen of competence.

Much of the overhyped discussion about ChatGPT seems to be confusing this language model for something approach artificial general intelligence. To me, it feels a lot like the advent of Siri and Alexa, with wild predictions that PCs would disappear and voice assistants would be everywhere. People really thought that their voice assistants understood their requests and had personalities—but the novelty has long-since worn off. I fear we’ve got a lot more not-very-funny ‘I asked ChatGPT…’ anecdotes still to live through, though, just as we endured ‘I asked Alexa…’ anecdotes long after they stopped being funny or insightful.

Like voice assistants, language modes are useful and will no doubt find a place in everyday use. And like voice assistants, that place won’t be nearly as central to our everyday experience as the early hype suggests, and nor will it be quite where we currently expect it to be.

And research towards artificial general intelligence will proceed apace—but honestly, I think it’s a stretch to say even that ChatGPT is a significant staging post on that journey.

The picture at the top of this post is an AI-generated image for the prompt ‘digital art of a robot in a bathroom applying talcum powder’ created by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, Technology, ChatGPT.

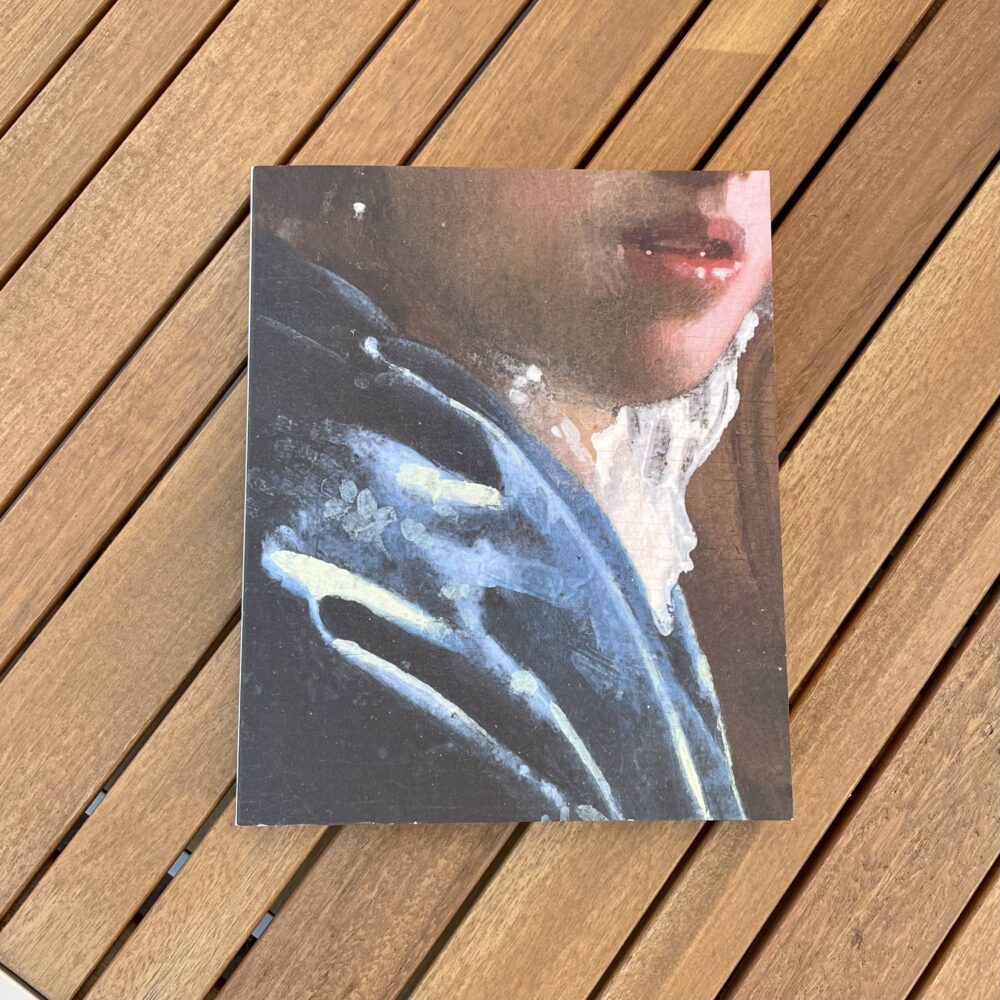

There are 37 paintings by Johannes Vermeer in this world, and the Rijksmuseum—for the first, and very possibly last, time in history—has gathered 28 of them in a single exhibition.1 I was lucky enough to go for a gander. And I mean lucky, because with over 200,000 tickets sold, this exhibition is sold out for months.

You’ll probably gather from the photos that I went into this exhibition with a slight sneer: here was an opportunity to see some pictures that are already familiar while peering over people’s shoulders and through their mobile phone screens. I’m not a fan of the sort of literal representative art that makes up Vermeer’s oeuvre. I was going as much to say I’d been as to actually see anything.

I’ve been lucky enough in my life to see any number of fantastically famous artworks, from the Mona Lisa to the Sistine Chapel. And every single time, it has looked just about exactly as I already knew it looked, and I felt no different for having seen it than I did beforehand. I wondered why I bothered.2

Vermeer was different. I don’t have the knowledge or language to properly explain why, but the experience of seeing these paintings in real life is remarkably different to seeing pictures of them. I think it’s something to do with their vibrancy: there isn’t a hint of dullness in the way there is in many historical paintings. They look, in some ineffable way, as though they are alive, or as though the paint is barely dry.

The exhibition was exceptionally well put together. The curators have avoided any muddying of the experience: there are no paintings by contemporaries for comparison, no works inspired by Vermeer to show his continued legacy, no blown-up reproductions to demonstrate his techniques. This is just the 28 Vermeers, spread across no fewer than ten galleries, giving each room to breathe.

Some paintings are on their own. It is objectively absurd to give The Milkmaid, a painting probably smaller than A3 size, an entire gallery to itself. And yet, it commands the space far more than Rembrandt’s huge Night Watch upstairs.

And nowhere in this exhibition does the visitor need to be hindered by bullet-proof glass, ‘which really gives the impression of being very close to the painting.’ Instead, a simple balustrade prevents crowding, but allows leaning over to get a closer look.

But obviously, it’s the paintings that are the star here. That unexpected, indescribable presence, the astounding attention to detail, the lifelike quality. They really are utterly unbelievable, completely astonishing.

I was so unexpectedly bowled over by the exhibition that I did something I’ve never done before with any exhibition: I went back the next day. I was so surprised by the strength of my own reaction that I couldn’t quite believe it, and wondered if I’d just been tired or overawed at being back at the beautiful Rijksmuseum. But no: the paintings really are spectacular, unlike anything I’ve ever seen before.

On my second viewing, I decided that the effect was a combination of the fine detail and the light: a lot of Vermeer’s paintings have a clear light source, often a window, and most of the light falls exactly as it would in reality. But there are exceptions: figures within the paintings seem to be lit more brightly than they probably should be. I think it’s this that gives the paintings such an arresting quality, and it most likely works best ‘in person’ because the light sources probably ‘read’ most correctly when the painting is on a wall. I know virtually nothing about painting, so this may well be a load of rubbish–but the fact that I’m spouting it demonstrates how much the Vermeers got inside my head.

Another illustration of how much the paintings struck me is that on my second visit, I bought the catalogue (I never buy the catalogue). And I know this is reaching a whole new standard of weirdness even for me, but the catalogue smells divine–a very intense new book scent. Oh, and the close-ups in it helped to deepen still further my appreciation of Vermeer’s eye for detail.

This exhibition wasn’t at all what I expected when I followed the blue line through the Rijksmuseum to find it: I’m very glad I went to it.

Vermeer continues at the Rijksmuseum until 4 June.

This post was filed under: Art, Post-a-day 2023, Travel, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Vermeer.

The content of this site is copyright protected by a Creative Commons License, with some rights reserved. All trademarks, images and logos remain the property of their respective owners. The accuracy of information on this site is in no way guaranteed. Opinions expressed are solely those of the author. No responsibility can be accepted for any loss or damage caused by reliance on the information provided by this site. Information about cookies and the handling of emails submitted for the 'new posts by email' service can be found in the privacy policy. This site uses affiliate links: if you buy something via a link on this site, I might get a small percentage in commission. Here's hoping.