30 things I learned in April 2021

1: I’m a bit obsessed with Max Richter’s 2012 recomposition of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons at the moment. Particularly, and unseasonably, Winter 1.

3: The economic generational divide in the UK is something that has played on my mind a lot over the years. It was one of my early pitches for inclusion in the CMO’s annual report, but as the health impacts are mostly in the future, it wasn’t something that was readily visible in surveillance data as yet.

We’re sailing toward an unprecedented crisis, with the burden of paying for the health and social care of the unusually large number of people born from the mid-40s to the early-60s likely to result in an unprecedented liability on those of working age: it’s simple maths.

Yet the same simple maths precludes an easy fix: there isn’t a democratic mandate for rationalising the approach as the median age of voters in the UK is 53.

This Propsect article gives a good overview of recent developments in how this has played out.

During the pandemic, 88 per cent of covid-related job losses affected Britons aged 35 and under, while employment among the more vulnerable over-50s rose.

It takes an average of 19 years to save for the deposit on a first home compared with three years in the 1980s.

“Deaths of despair” (those from suicide and addiction) strike each successive generation at a younger age, and their numbers are increasing. The proportion of young people with diagnosed mental health problems is roughly equivalent to the proportion of over-65s who are millionaires: one in five.

I think it is inevitable that this will lead to social unrest. It is surely impossible to avoid while choices such as triple-locking the basic state pension paid to millionaires while funding cuts mean that student leave university an average of £50,000 in debt. But social unrest only adds to our list of problems.

I have no idea how we can fix any of this. Even if older voters (and politicians) can be persuaded to propose and support politics against their immediate best interests, those very cuts might end up making this generation less healthy and (paradoxically) more costly: four in five aren’t millionaires, and even those who are don’t necessarily have liquid assets.

It’s hard not to imagine that this, along with privacy and climate change, will prove to be one of the dominant long-term societal challenges of the first half of the 21st century.

4: Murder in outer space would be a legally knotty affair.

6: It sometimes feels like we’re in an extremely turbulent political period, but on one measure it is remarkably stable: in my lifetime, there have only been handovers between Prime Ministers from different parties twice (John Major to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown to David Cameron). We haven’t had a similarly stable period in this regard since the 1700s.

9: “I don’t have remorse and won’t acknowledge failure,” said President Macron in March. I don’t think I’ve ever heard a senior politician sound more like a DSM-5 entry.

11: Jonathan Rothwell’s blog post about the London mayoral election has sent me into a bit of a spiral of thought. “It does rub me the wrong way that there appears to be so little choice—and when there is more than just a binary choice between two ancient political parties, neither of whom appear to have your best interests at heart, the machinery of national politics is willing to snatch even that away.”

It makes me worry that I’m part of the problem. I have no desire at all to get involved in politics: I struggle to imagine anything worse than spending my time having to constantly defend my basic interpretation of reality. It makes me think of heart-sink meetings with anti-vaccine councillors. I completely understand the importance of having those conversations and explaining the science to people who are making local policy decisions, but I it isn’t something I’ve ever enjoyed. The idea of a professional life that involves a lot of that is unappealing. Adding a layer of party politics, in which one has to defend positions one personally finds indefensible simply because it is the ‘party line’, just makes the prospect even grimmer.

And yet: does this not make me part of the problem? If I’m not willing to engage, why should anyone else bother? Are people who enjoy party politics really the people we want making decisions on our behalf? Shouldn’t we all engage more for the good of society? Is “I don’t want to” just a selfish whinge? How can things improve if we leave politics only to those who can be bothered? Aren’t decisions made by those who show up?

12: Work has brought a surprising amount of discussion of stevedores recently, which is a delightful crossword word.

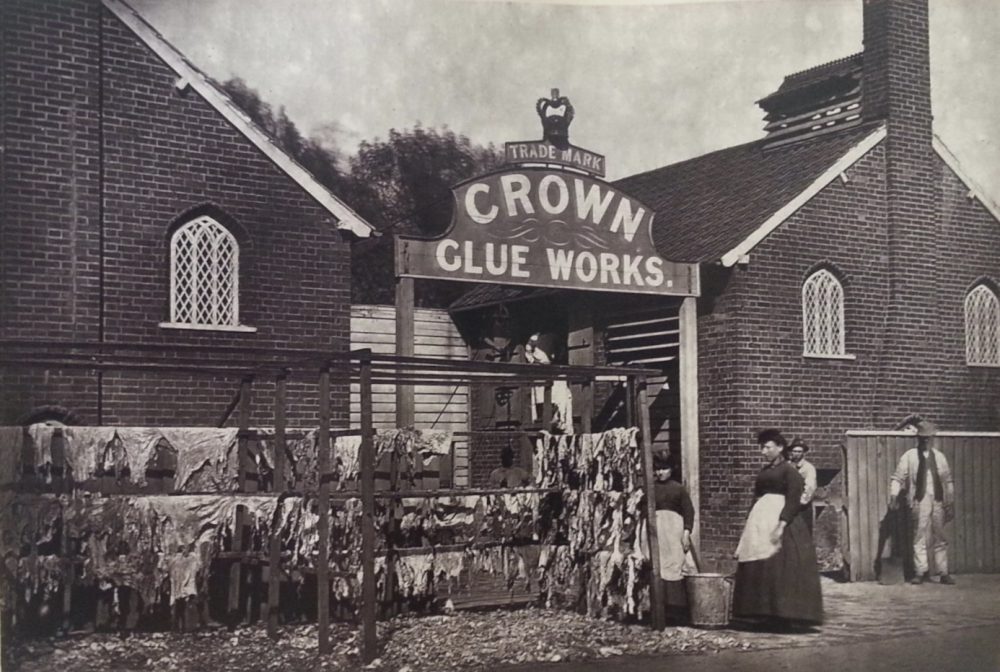

13: It feels like there must be a story behind the placement of this sign.

14: Last week, the MHRA and DCMO used some excellent slides from the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication (David Spiegelhalter’s stomping ground) to illustrate the risk of serious harm associated with receiving the AstraZencia covid vaccine.

This got me thinking: how does the risk of the vaccine itself compare with the risk of participating in the programme as a whole? In particular—given that most people live “within 10 miles” of a vaccination centre—how does it compare with a 20-mile round trip by car?

After much searching through evidence, my boring conclusion is that they’re focusing on absolutely the right bit of the programme, and the risk of serious harm associated with the journey is orders of magnitude smaller and probably negligible, even at this scale of rollout.

I should have known better than to doubt them!

15: The last Routemasters have run in passenger service.

16: From Concretopia, I learned about Cumbernauld town centre, one of Britain’s most hated buildings. I’m amazed I haven’t come across it before.

17: Derwent Reservoir is spectacular in the spring sunshine.

And as though to prove that it’s spring, here are some ducklings.

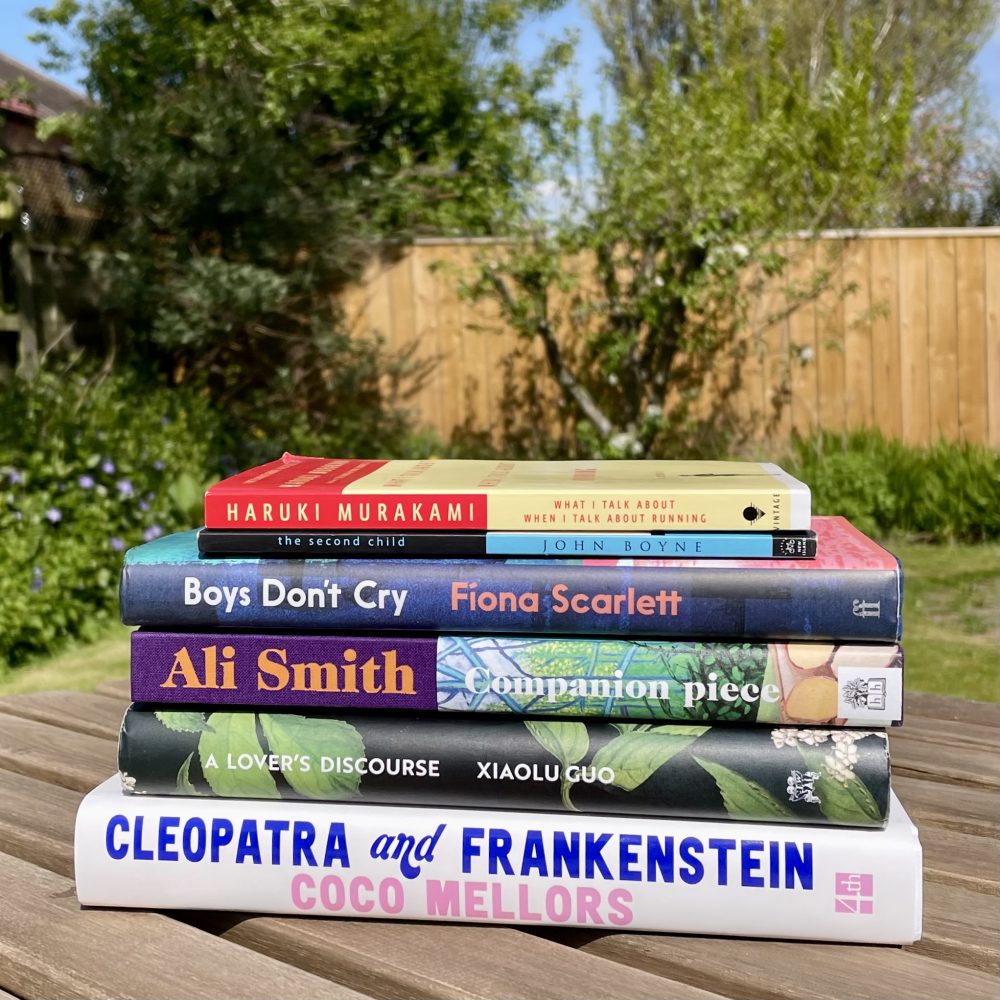

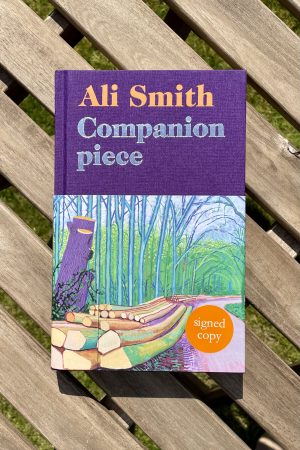

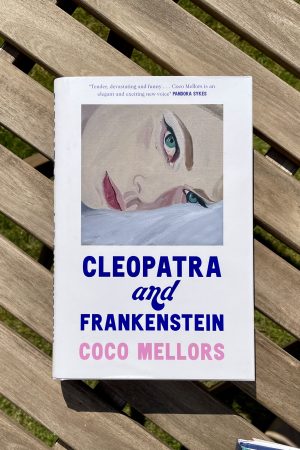

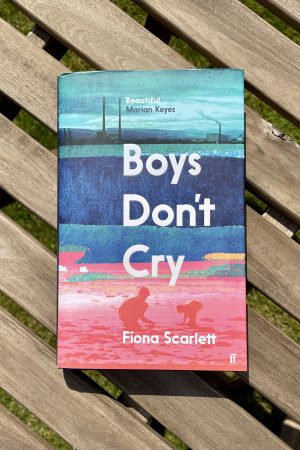

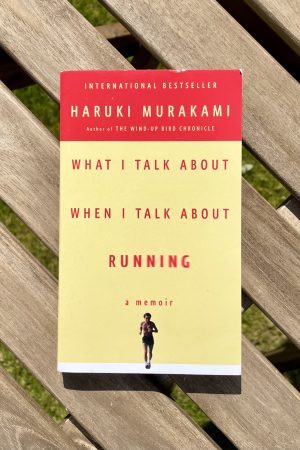

18: People often talk to me about books, because they know I’m interested in reading and they follow me on places like Goodreads. I find these conversations difficult, never quite knowing what to say or how to say it. I had a moment of stunning clarity this week when talking to a colleague about this: their suggestion was that it’s easier to write about books because books themselves are written-word.

I think there’s something in that. I’ve always been useless at dictating because speaking isn’t the same as writing, and they need different parts of my brain. In the days when I did clinics, I was far faster at typing my own clinic letters than dictating for a secretary.

For the same reason, I got more confident at public speaking when I stopped trying to write presentations out and relied on freely talking around the key points instead. And, probably for the same reason, I find it hard when I phone a company and they ask for a security word (or whatever) that I’m used to typing instead.

So why wouldn’t the same apply to talking about books?

This conversation came back to me this morning as I read Courier Weekly: “One of the best parts about reading a book is getting to talk about it with other people.” Mmm, maybe not.

19: Fran Lebowitz says that “your bad habits will kill you, but your good habits won’t save you.” It’s possibly the most accurate public health aphorism I’ve ever heard.

20: The news that some teams want to play in a new football competition is dominating the papers and bulletins to an extraordinary extent—and no matter how much I read about it, I’m continue to struggle to understand what the problem is, mostly because I’m not really familiar with how football competitions work at the moment (and struggle to care).

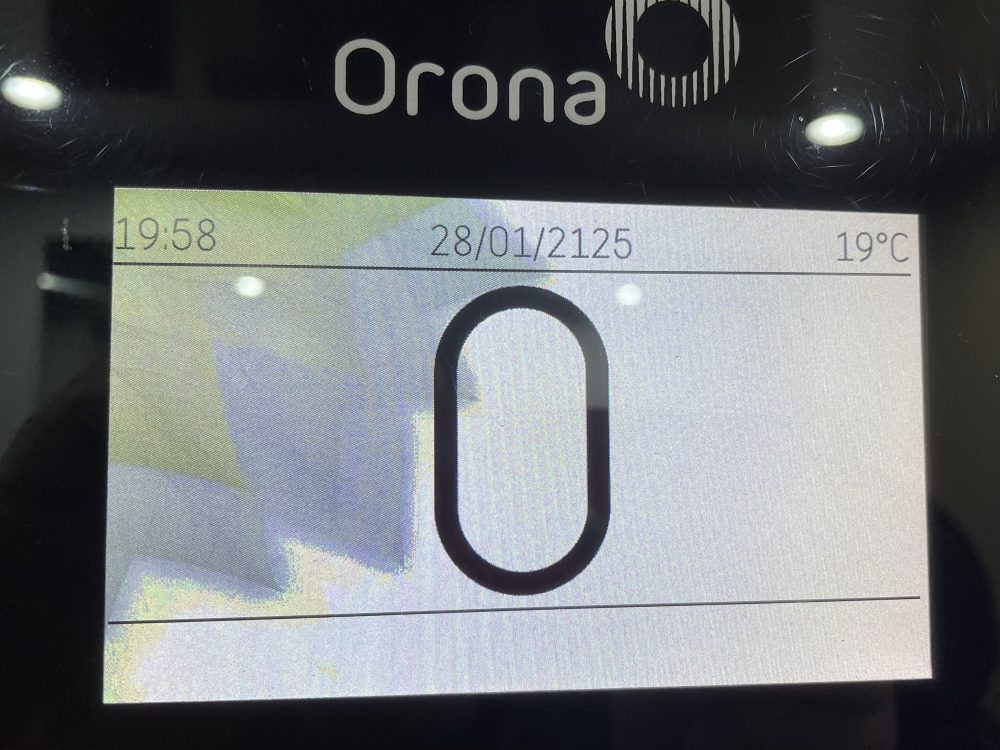

21: I’m still a promising thirty-something.

22: The Government has changed its mind about holding daily televised press briefings, seemingly for reasons which were perfectly obvious from the start. I’m sure that spending 13 times more on refurbish a room for these cancelled briefings than on helping 15,000 displaced Commonwealth citizens affected by a volcanic eruption is entirely justifiable.

24: That Yes Minister bit about who reads which newspaper is older than I realised.

26: One needn’t be a doctor to become one of the US’s Top Doctors.

For all the hand-wringing about President Trump’s destruction of any form of trust in Government communications, it seems no lessons have been applied to the UK government. When the judgement of the UK media is to disbelieve statements from the Prime Minister’s spokesperson and from his own mouth, we’re in a bit of a sorry (if entirely predictable) state. And, just like Trump, the liar remains popular with the public.

28: Starbucks has on the wall of one of its branches the claim that 99% of its coffee is ‘sourced ethically.’ I’ve been slightly reeling ever since I saw it: Who decided that acting unethically 1% of the time was boast-worthy behaviour? It seems like an active admission of guilt, which obviously doesn’t come as a surprise with that chain, but it still seems amazing that some corporate communications team signed it off. I half expect to see a ‘we’re proud to intentionally overcharge just 1 in every 100 customers’ sign in the next branch I venture into, or perhaps ‘99% of our baristas are paid in full.’ Baffling.

29: The Dixons brand of electronics stores is about to disappear for good, a little over fourteen years after I wrote that Dixons was “to stop selling anything. To anyone. Ever.” You heard it here first.

30: I have seen film posters with the line “in virtual cinemas now”—and I’m really not sure what that means. I thought it probably just meant available to stream, but then an ad for Truman & Tennessee said “in virtual cinemas and on demand now – book now” which seemed to rule that out.

This post was filed under: Posts delayed by 12 months, Things I've learned.