A broken nation

On May 31, 2003, on an unusually warm spring day, I arrived in London somewhat by chance. I was living in Thailand at the time, and my partner had found a job in the UK capital. Arriving with no particular preconceptions, I discovered a surprisingly dynamic country, open to the world and happy with its multiculturalism.

At the time, the French were arriving in droves. An organization was set up to welcome young adventurers who arrived on the Eurostar with their rucksacks, helping them find a job and accommodation within a matter of days. At the other end of the social spectrum, graduates of France’s top business and engineering schools were snapping up trading jobs in the City. The fee-paying French Lycée in London could no longer keep up with demand.

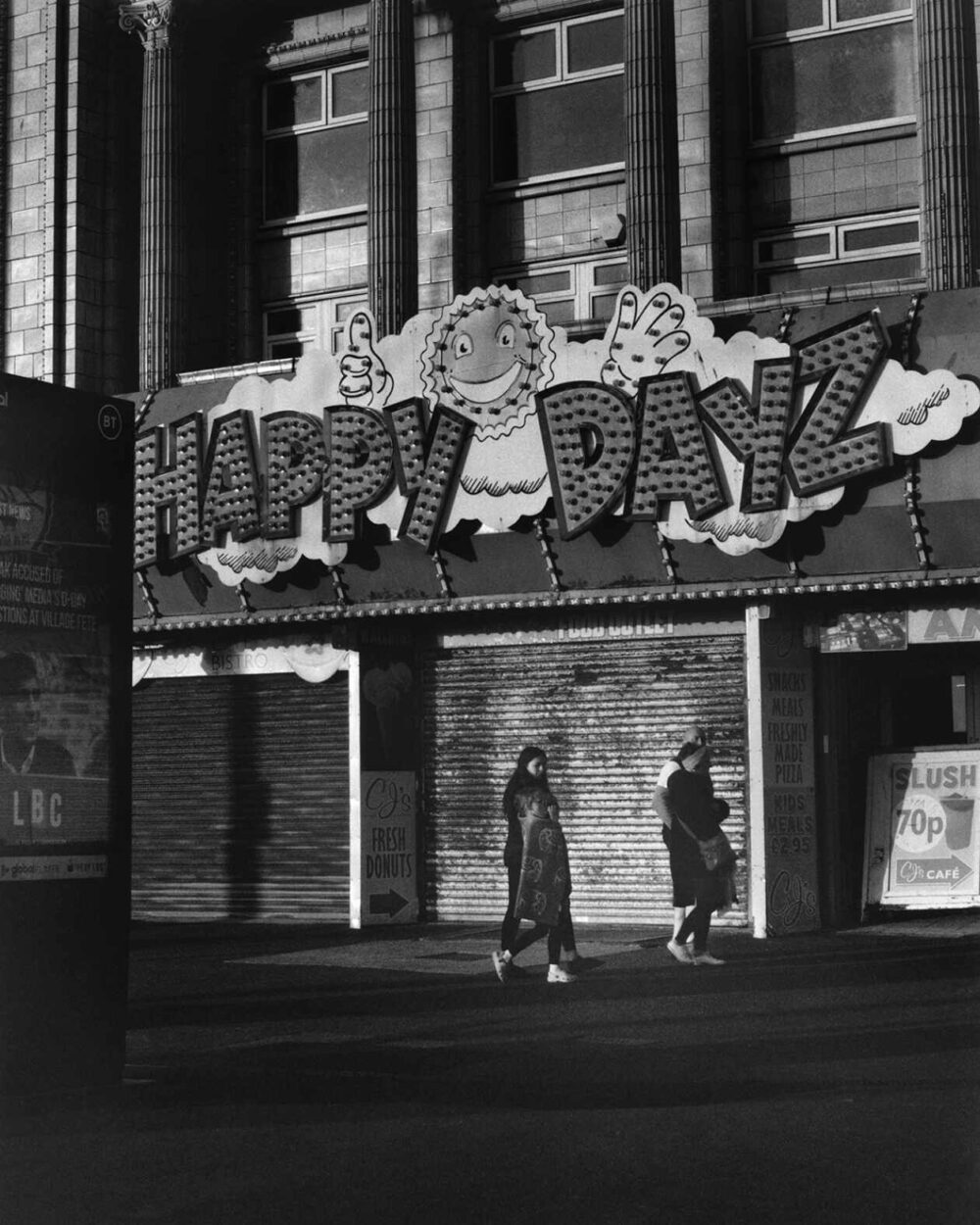

Twenty-one years later, I’m about to return to France for professional reasons. The UK I’m leaving bears no resemblance to the one that welcomed me. The pound has fallen by almost 20%, immigration has become an obsession and the French Lycée has closed its doors, after many families left.

It is well worth reading the whole thing. The distance afforded by both time and an outsider’s perspective brings into sharp relief the sense of decline across the country.

It feels to me like so much of our election coverage in the UK focuses on the political parties rather than the state of the nation. I think Albert’s article offers more insight into the state of the election polls than any number of headlines about senior Tories’ alleged gambling crimes, or any other of the myriad campaign gaffes. The campaign isn’t working because the country isn’t working.

I was particularly struck by Albert’s mention of James Picken, a Hartlepool resident. It feels to me like this sums up so much:

Picken’s story is complicated. The 42-year-old didn’t need the current British decline to fall into poverty. His mother died of a Valium overdose when he was 15. His brother died of a heroin overdose. Having been a welder on gas platforms and worked in Norway, among other places, he then fell into a downward spiral. Alcohol, drugs and prison – the vicious circle began almost two decades ago.

What has been more recent is the harshness of the system, which pushes him back into a rut each time he tries to climb out of it. A few months ago, he missed an appointment at the Jobcentre state employment agency. The penalty was immediate. “Normally, I get £276 in welfare benefits every month. My rent is taken care of, but that has to cover all my bills – electricity, gas and phone – and all my food. After the penalty, I only got £18 for the whole month.”

What was bound to happen happened: Picken stole a stash of chocolate bars (“I was craving sugar”) and some chicken from a store. “When I got caught, I was almost relieved, thinking that at least in prison I’d have two guaranteed meals a day.” This system infuriates Bedding from the Annexe organization. “Who benefits from this situation? We put him in prison for eight weeks, which cost society thousands of pounds, because they wanted to save £200 initially on his welfare benefits. What was the point?”

‘What was the point?’ is, perhaps, a question with wider relevance and resonance.

This post was filed under: News and Comment, Politics, Eric Albert, Le Monde.