Iridescent irises

I recently began reading The Tortoise and the Hare by Elizabeth Jenkins, first published in 1954. Early on, Jenkins describes a character’s dark eyes, and where I would use the word ‘irises’, Jenkins used the word ‘irids’:

Her skin had the warm whiteness of marble in sunlight, her eyes were so dark the irids were indistinguishable from the pupils; the whites were a pale blue.

Why have I never seen or heard the word ‘irids’ before? Where did it come from? Why don’t we use it anymore?

As it turns out, the distinction between the words is not massively clear: as you’d guess, they share an etymology.

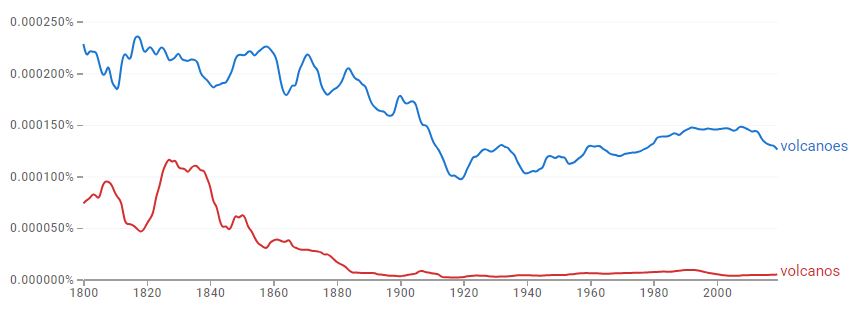

Certainly, ‘iris’ is more common than ‘irid’ these days, though some people prefer ‘irides’—with that extra ‘e’—as a plural form rather than ‘irises’. Indeed, ‘irides’ is listed in the 1900 OED as the preferred plural. There are two iris-related adjectives listed in the OED, both of which prefer a ‘d’ over an ‘s’: ‘iridal’ and ‘iridic’.

Comparing the frequency of usage of ‘irid’ and ‘iris’ is complicated by the fact that ‘irid’ is specific to the structure in the eye and the genus of plants, whereas ‘iris’ can also refer to the Greek goddess, a shape of crystal, and an asteroid—among other things.

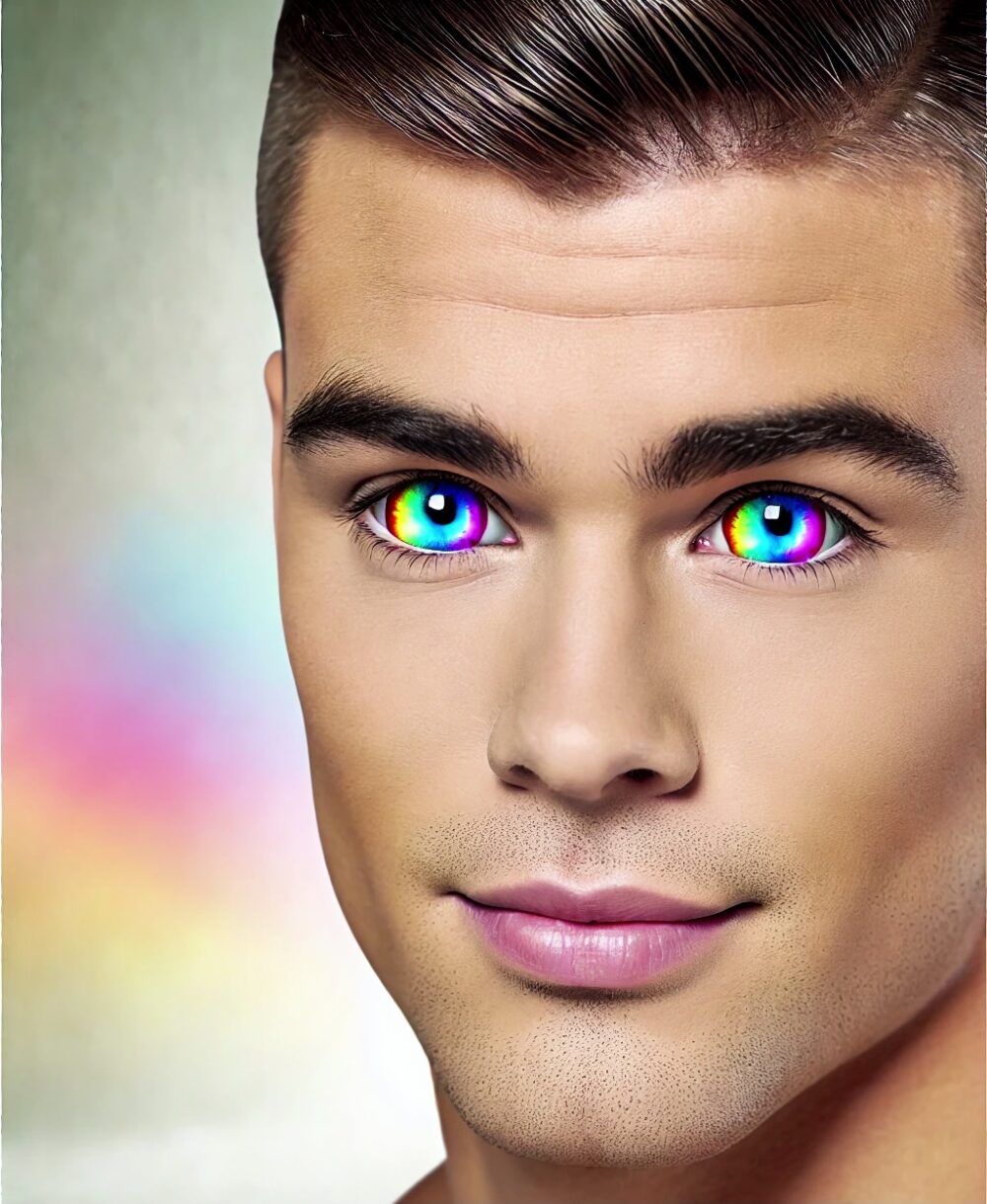

One of the other things that can be described as an ‘iris’ is a rainbow. You might think you’ve never heard of this usage, but you probably have—just with a ‘d’ form of the word. The much more common word ‘iridescent’ is used to describe items that show many different colours when seen from different angles. ‘Iridescent’ is an adjective related to ‘iris’ in its ‘rainbow’ sense.

The preference for ‘iris’ as the anatomical term seems to have followed the standardisation of terms as medical publishing became a thing: Gray’s Anatomy has consistently used ‘iris’ since its first publication in 1858, and most textbooks—and latterly medical journals—followed suit. As medical science advanced rapidly in the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a strong push towards the standardisation of medical terms to ensure clear communication between medical professionals: see also the virtually total replacement of ‘apoplexy’ with ‘stroke’, of ‘consumption’ with ‘tuberculosis’, and of ‘dropsy’ to ‘oedema’.

Curiously, though, ‘irid’ was already pretty uncommon by the time Jenkins’s novel was published: its frequency of usage was similar to today’s. It was, however, much closer to its peak fifty years earlier, when Jenkins would have been growing up—so perhaps it was lodged in her lexis.

Perhaps in a similar way, I sometimes get teased for using certain words in medical notes: ‘don’ and ‘summarily’ are two examples. Both are words whose usage has collapsed since the decade when I was born, but which seem like perfectly ordinary, everyday words to me. As it happens, both were also less common in the 1950s than in the 1980s: the popularity of words can rise as well as fall.

The image at the top of this post was generated by DALL·E 3.

This post was filed under: Miscellaneous, Elizabeth Jenkins, Oxford English Dictionary.