Animals are often reluctant to show their bellies as they are a soft, vulnerable point for predators to attack. This debut novel by Dinan, aptly titled Bellies, is about people who become close enough to be vulnerable with one another, to show each other their metaphorical ‘bellies’. It’s about the emotional vulnerability the characters allow themselves to experience in their relationships.

The novel centres on Tom and Ming, who take turns to narrate. Tom is a slightly awkward, newly out gay student. Ming is a charismatic young gay playwright from Kuala Lumpur. The two fall in love and move to London together. Things become complicated when Ming decides to transition to living as a woman.

Having just finished reading Jan Morris’s Conundrum, a renowned book on transsexuality, I thought it couldn’t be a coincidence that a couple in the book are called Janice and Morris: it must surely be a reference.

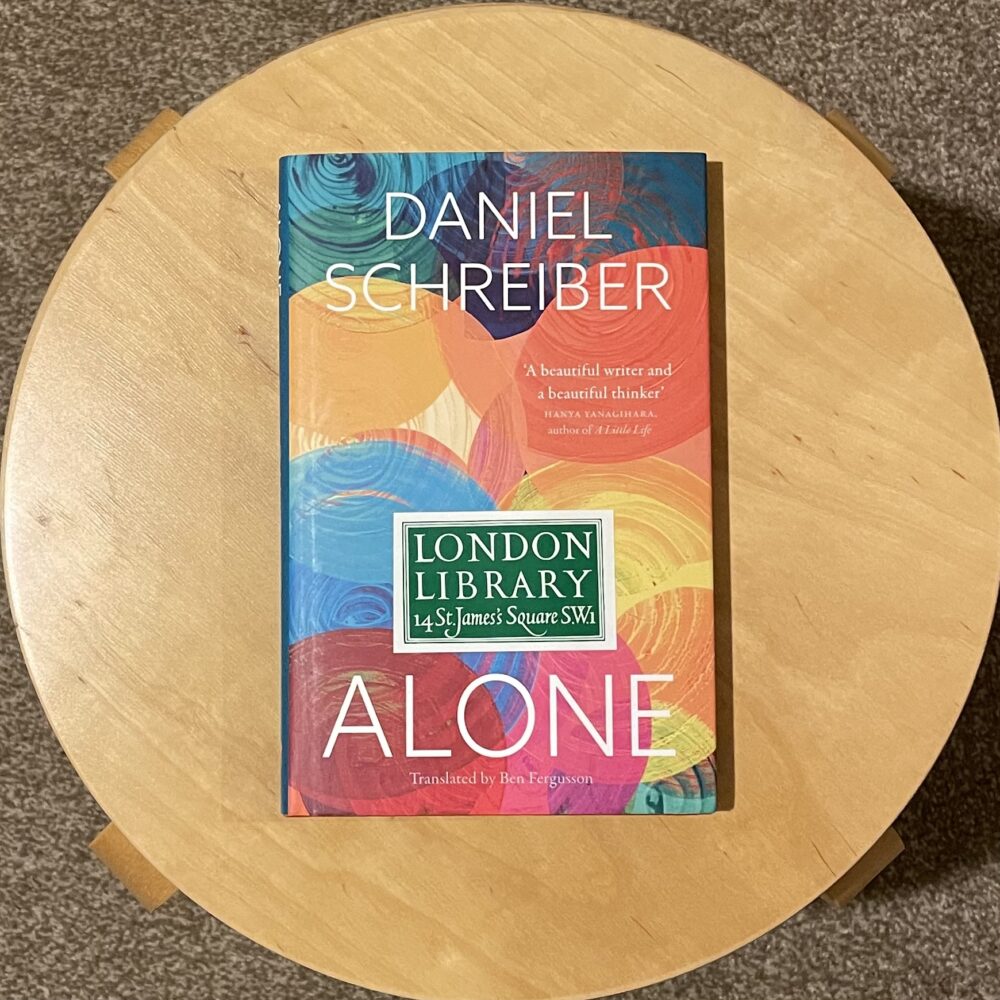

But really, the book is about so much more than the central relationship and certainly about more than transsexuality. It’s a novel about a group of young friends, and it reflects how their relationships and dynamics change as they grow up and take sometimes divergent and sometimes convergent paths through life. In that sense, it reminded me of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, though covering a slightly shorter timespan and with a little less bleakness.

The characters, even the supporting cast, felt real to me, with true human irrationality and unlikability at times. The book is suffused with both humour and tenderness. There is a speech at a funeral in this book, which conjures an image that I think might stay with me for the rest of my life.

Overall, this was a brilliant novel, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. It might be the first I’ve reviewed this year, but I’m sure it will be one of my favourites of 2024. I’m already thinking of people to recommend it to.

Here are some passages I highlighted. There are quite a few: I really liked Dinan’s turn of phrase and ability to capture a mood or idea in just a few words. She’s an incredible writer.

I’ve censored the first one so it doesn’t become a spoiler.

I’ve been thinking about how the trunks of trees bend and curve when they grow next to each other. Their leaves twist to accommodate each other. Their closeness reads on the shape of them, and you can infer the shape of one from the shape of another. When you know someone and you grow together, your shape and form become theirs. And so even though X is gone, and there’ll never be another X, another friend I’ve know as well or as closely, the impression their life left on me will always be there, and in that sense we haven’t lost them at all.

I shouldn’t use the word crazy, but I feel like I can. In the same way I can call myself a faggot. Sometimes the shoe fits if you put it on yourself.

Amateur pottery always looked shit, fermentation was just a lot of waiting around, and marathons were for people who had something to run away from.

We walk upstairs together towards my room. I look at my messy, unaccommodating desk. Tom hates how my belongings splat over any surface like jam.

Next to Ming’s, my own mind felt flat, a city highway and not a winding road with sharp loops and swerves. Ming’s thoughts seemed an exciting place to be, a lucky thing to experience.

Everyone laughs. The joke’s not even funny, but there is a collective yearning to shift the mood. The shakes in our ribs are enough to connect the empty spaces between the chairs and across the table. The conversation turns light.

‘Do you want to be a woman?’ I asked.

‘I don’t even know sometimes. I think so. But then I ask myself what does living as a man or woman even mean?’ He shook his head. ‘And I tell myself it’s all sexism, but at the same time it’s a sexist world, and those things still mean something, you know.’

I’m not being funny, but I don’t really know what I like or care about any more.

Maybe that’s what people are supposed to do, sponge out the bad, wring out the suffering as much as we can, even if it stains our hearts and hands.