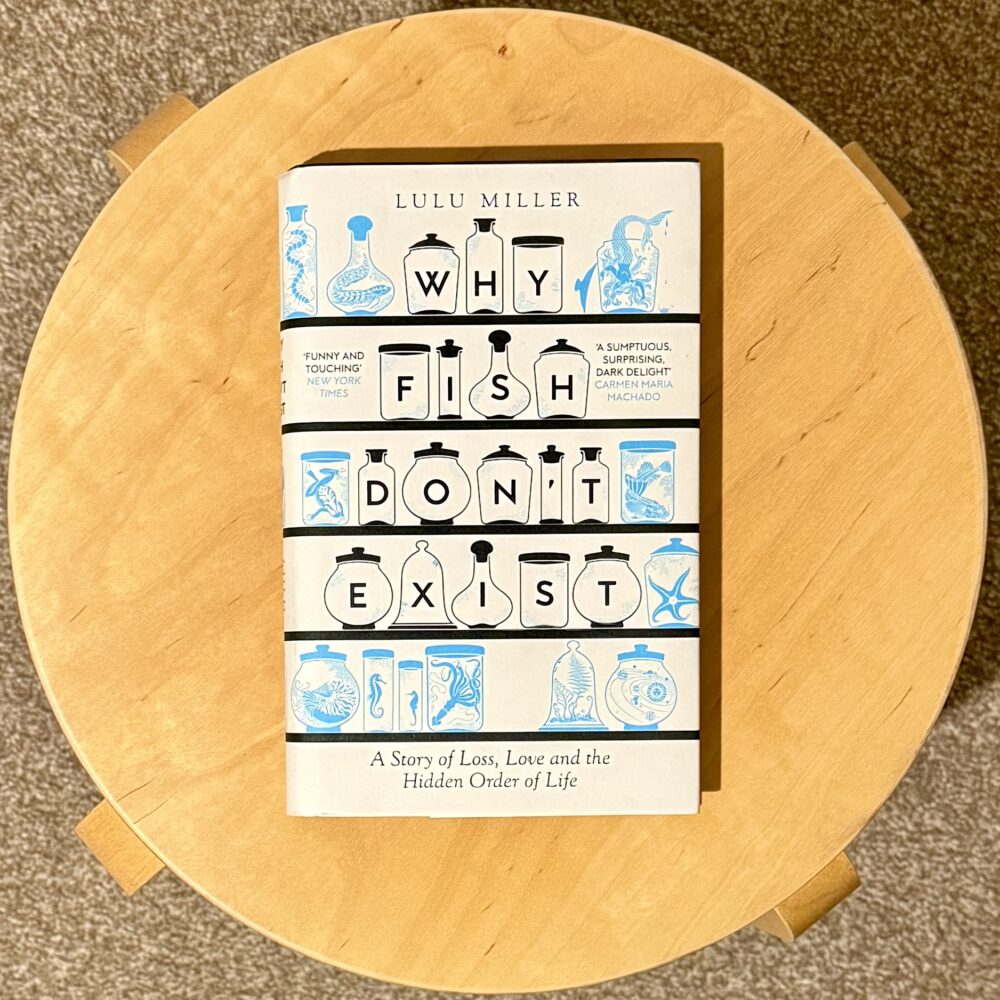

This book was recommended by lots of bookish writers so often that I bought it without really knowing much about it. The blurb gave me a signpost:

David Starr Jordan was a taxonomist, a man possessed with bringing order to the natural world. In time, he would be credited with discovering nearly a fifth of the fish known to humans in his day. But the more of the hidden blueprint of life he uncovered, the harder the universe seemed to try to thwart him. His specimen collections were demolished by lightning, by fire, and eventually by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake—which sent more than a thousand discoveries, housed in fragile glass jars, plummeting to the floor. In an instant, his life’s work was shattered.

Many might have given up, given in to despair. But Jordan? He surveyed the wreckage at his feet, found the first fish that he recognized, and confidently began to rebuild his collection. And this time, he introduced one clever innovation that he believed would at last protect his work against the chaos of the world.

When NPR reporter Lulu Miller first heard this anecdote in passing, she took Jordan for a fool—a cautionary tale in hubris, or denial. But as her own life slowly unraveled, she began to wonder about him. Perhaps instead he was a model for how to go on when all seemed lost. What she would unearth about his life would transform her understanding of history, morality, and the world beneath her feet.

From this, I expected a slightly twee inspirational story linking this esoteric moment of scientific discovery to Miller’s own challenges, and to conclude with a sweet reflection on the nature of resilience.

I think it’s best to go into this blind, so I won’t say too much, other than: blimey, I underestimated this. This is quite unlike anything I’ve ever read before: part biography, part memoir, part biology, part philosophy. It is beautifully written, with Miller’s passion and curiosity dripping from every page. She clearly poured her heart into this—and it feels like this is the perfect cultural moment for it.

This was so good that I ended up photographing quotations and sending them to Wendy on WhatsApp as I read—I can’t remember doing that before.

It’s less than 200 pages, and I think it is well worth anyone’s time.

I highlighted lots in this book; here are some good bits that hopefully don’t spoil anything:

Imagine seeing thirty years of your life undone in one instant. Imagine whatever it is you do all day, whatever it is you care about, whatever you foolishly pick and prod at each day, hoping, against all signs that suggest otherwise, that it matters. Imagine finding all the progress you’ve made on that endeavour smashed and eviscerated at your feet.

The “soul-ache … vanishes,” he writes, “with active out-of-door life and the consequent flow of good health.” He claims that salvation lies in the electricity of our bodies. “Happiness comes from doing, helping, working, loving, fighting, conquering,” he writes in a syllabus from around the same time, “from the exercise of functions; from self-activity.” Don’t overthink it, I think, is his point. Enjoy the journey. Savour the small things. The “luscious” taste of a peach, the “lavish” colours of tropical fish, the rush from exercise that allows one to experience “the stern joy which warriors feel.”

To some people a dandelion might look like a weed, but to others that same plant can be so much more. To an herbalist, it’s a medicine—a way of detoxifying the liver, clearing the skin, and strengthening the eyes. To a painter, it’s a pigment; to a hippie, a crown; a child, a wish. To a butterfly, it’s sustenance; to a bee, a mating bed; to an ant, one point in a vast olfactory atlas.

And so it must be with humans, with us. From the perspective of the stars or infinity or some eugenic dream of perfection, sure, one human life might not seem to matter. It might be a speck on a speck, soon gone. But that was just one of infinite perspectives. From the perspective of an apartment in Lynchburg, Virginia, that very same human could be so much more. A stand-in mother. A source of laughter. A way of surviving one’s darkest years.

One day, while riding bikes along the Potomac River, she started racing me, and I couldn’t catch her. I ran five miles most days. And I couldn’t catch her. I liked that feeling. Her mind was faster than mine, too. She could drum up dazzling rants about tentative drivers, about scrambled eggs, about people who sign their emails with only one initial. “Are you that busy?!” she groaned. “Are you that beholden to the cult of overwork that you need to communicate that you do not even have those four milliseconds to spare?” She had a way with words.

The best way of ensuring that you don’t miss them, these gifts, the trick that has helped me squint at the bleakness and see them more clearly, is to admit, with every breath, that you have no idea what you are looking at. To examine each object in the avalanche of Chaos with curiosity, with doubt. Is this storm a bummer? Maybe it’s a chance to get the streets to yourself, to be licked by raindrops, to reset. Is this party as boring as I assume it will be? Maybe there will be a friend waiting, with a cigarette in her mouth, by the back door of the dance floor, who will laugh with you for years to come, who will transmute your shame to belonging.

My wife stirs in bed next to me. She slaps my shoulder. “Pipe down, Flipper,” she mumbles. Referring to the fact that I am flipping, tossing and turning, unable to sleep. She wants me only to join her in peace, in slumber, in the soft cotton waves of our powder-blue sheets. I clutch the brimming warmth of her thigh and think about the fact that even at its most hopeful, my measly brain could have never dreamt up something as infinitely intoxicating as her.