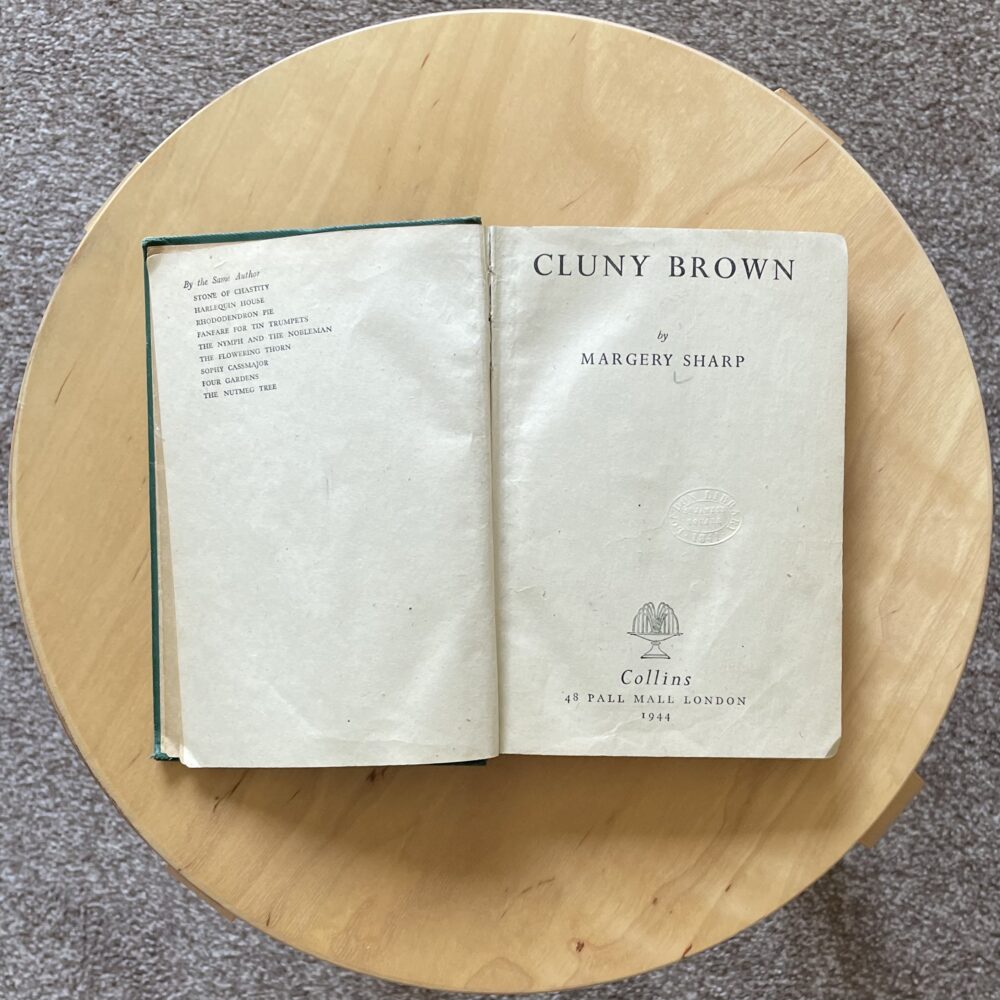

‘Cluny Brown’ by Margery Sharp

I borrowed this 1944 novel from the library after seeing it featured in the New York Times newsletter Read Like The Wind. I found it to be a funny and gently comforting read.

The book is set in England in the late 1930s, and the titular character is an orphan in her twenties whose self-confident temperament does not fit the social mores of the time. Uninterested in what is ‘right’ and ‘proper’ for a young lady, she ploughs her own furrow with innocent charm.

In an attempt to get her to conform to her social standing, her uncle sends her into ‘service’ as a parlourmaid in a large country house, with amusing consequences. On the surface, this novel is a traditional farce, but scarcely beneath the surface, Sharp uses that comedy to skewer pretty much all contemporary societal norms. The looming war doesn’t escape judgement either.

Sometimes, I read historical novels and find them a bit of an effort, even if that effort is rewarded by what I take away from them. Not so this book: the pages flew by, and the humour was right up my street. It didn’t feel like I was reading something that was eighty years old.

Some highlights:

She had got to the Ritz. She had got as far as Chelsea—put her nose, so to speak, to a couple of doors—and each time been pulled back by Uncle Arn, or Aunt Addie, people who knew what was best for her, only their idea of the best was being shut up in a box—in a series of smaller and smaller boxes until you were safe at last in the smallest box of all, with a nice tombstone on top.

“She likes to see a young lady who doesn’t put stuff on her face,” said Mr. Wilson. “If I may say so, so do I.”

“Well, it wouldn’t do any good,” said Cluny frankly. “I’ve tried it, but I look worse.”

“They all look worse,” said the chemist. “Only they haven’t the sense to know it.”

The bluntness of a friend in pain is never hurtful.

“Please can you lend me a good book?” he asked politely.

Before answering Betty switched on a second light, which thoroughly illumined the whole room. The conjunction of a highly desirable appearance with a great deal of sense had inevitably taught her much that young girls were not commonly supposed to know: for instance, that a strong light is almost as good as a chaperone.

“Darling,” said Andrew, as they finished their coffee, “would you like to marry me next month?”

“No, thank you,” said Betty. “What a fool idea, darling.”

I have so often thought how in all English art the place of women is taken by landscape. Your poetry is full of it, you are a nation of landscape painters. In other countries a man spends his fortune on a mistress; here you marry a fortune to save your estates.

If you had a smattering of education you would realize that perfection of form can give validity to any sentiment, however preposterous.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Margery Sharp, The New York Times.