‘The Great Mughals’

I was reminded recently of a line from The West Wing:

Toby, the total tonnage of what I know that you don’t could stun a team of oxen in its tracks.

This is almost certainly true in the context of this blog, too. You, dear reader, know an awful lot of things that I don’t know.

When I wandered passively into the V&A’s exhibition on The Great Mughals, I couldn’t have told you the first thing about them. And, to be honest, the explanatory text mostly went above my head. It was only roughly half way through that they explained that one of the Mughals was behind the Taj Mahal, and that they used to be referred to in English as Mongols, that I began to get my bearings a little. Even so, it turned out to be one of those encounters with history that leaves me quietly uncertain about what I’ve taken from it.

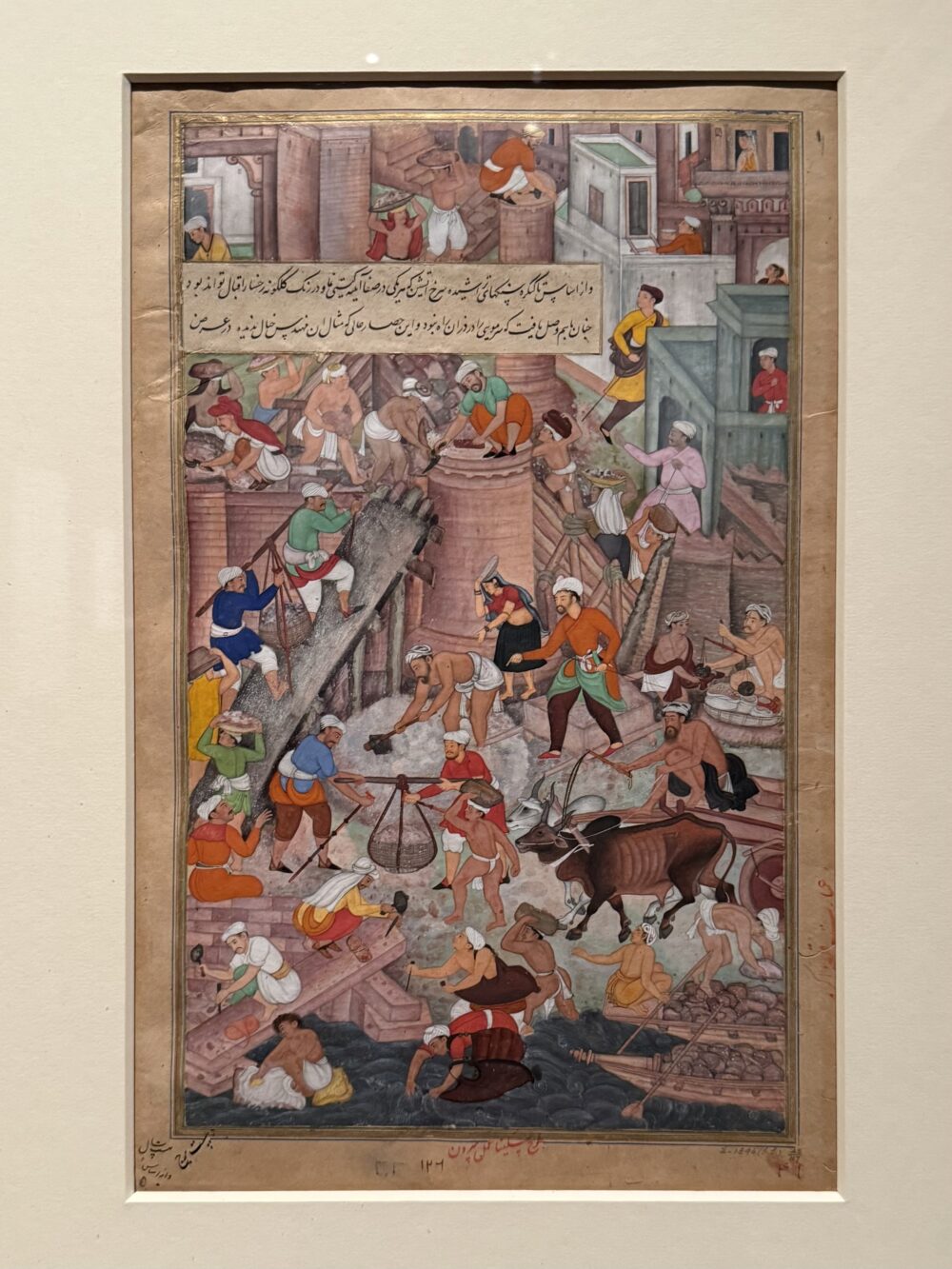

The exhibition is beautiful. It’s hard not to admire the level of craftsmanship in the miniature paintings, the jewellery, the manuscripts. There’s a kind of serene intensity to the objects on display, each one a product of unimaginable labour, precision, and—often—wealth. The story of the Mughal Empire is told largely through the lens of splendour: the grandeur of architecture, the opulence of court life, the flourishing of art and science. It is all, in a word, impressive.

And yet, I found myself struggling to settle into the experience, and not just because of my disorientation. I moved through the exhibition more quickly than I’d intended, glancing rather than lingering, admiring rather than absorbing. I often find it difficult to look at exquisite objects created for emperors and princes without also thinking about the systems that made them possible. Who carved the emeralds? Who was pressed into the service of empire so that an emperor might commission a manuscript in gold leaf? These aren’t questions the exhibition ignores, exactly—but nor do they sit at the centre. The narrative is one of cultural flourishing, not of domination or inequality. That’s understandable, perhaps, but I came away feeling that the absence of discomfort had left me a little uncomfortable.

I don’t mean to sound overly cynical. I’ve ranted at length about the British Museum’s insistence on interpreting stolen artefacts from a British perspective, and literally plastering ‘British’ over display cases containing objects which are anything but. I didn’t feel that here: the focus on design dampened the potential for cultural insensitivity, somehow. The objects on display are extraordinary, and there is joy in seeing them up close.

Yet, I wonder if the framing of exhibitions like this one leans too heavily on admiration—at least for a visitor like me, prone to squinting at power structures. I’m left wondering whether I’ve simply failed to meet the exhibition on its own terms.

Still, I’m glad I went. There’s something quietly humanising in grappling with a past that doesn’t neatly align with contemporary instincts—especially one rendered in so much turquoise and lapis. Even if I didn’t quite connect, the effort of trying to felt worthwhile. And perhaps that’s enough for an afternoon.

The photo shows an image of the construction of the Agra fort from a manuscript illuminated in about 1590. I took it quite furtively, as I wasn’t completely sure whether photography was allowed. Nevertheless, the exhibition continues at the V&A until 5 May.