We rage against the dying of the light

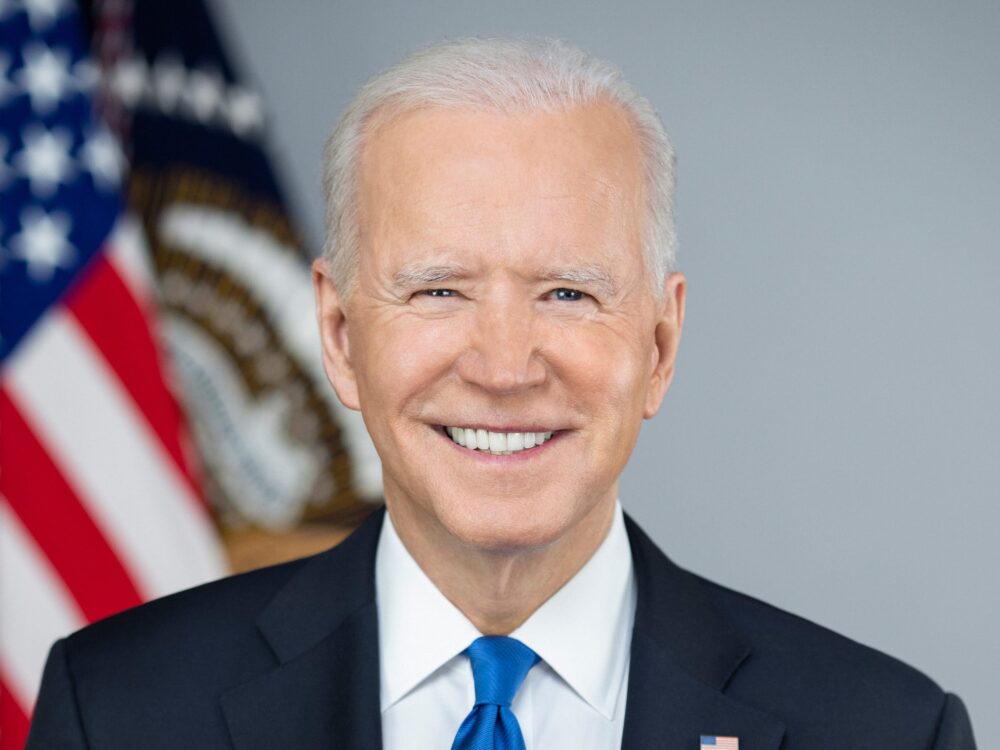

In the final seconds of BBC One’s Weekend News bulletin yesterday, Reeta Chakrabarti squeezed in an extra story in just 25 words:

Just before we go, President Biden has just tweeted that he intends to address the nation later this week, saying that it has been a great privilege to serve. We’ll bring you more at ten.

We know now, of course, that in the judgement of mere seconds, the team had perhaps overlooked the more significant message of Biden’s message: his decision to withdraw from his re-election campaign.

It’s not hard to see why: Biden’s statement refers only to standing down, without complete clarity on what from. It’s a letter that’s hard to parse on a scan-read, with the eyes of a nation watching.

Wendy and I switched over to the news channels, and after minutes of slightly desperate filling, the airwaves were thick with discussion of the political consequences of the decision, with hot takes and commentary on who might replace him and what it may mean for an election that’s still months away.

Nobody seemed keen to take a step back. It’s not hard to imagine the sense of profound grief Biden must feel at this moment. This is surely a moment that marks a painful shift in the way Biden sees himself: judged irreversibly incapable by dint of age of doing something he’s done before.

As Peter Wehner wrote in The Atlantic last night:

Coming to terms with mortality is never easy. We rage against the dying of the light. Many elderly people face the painful moment of letting go, of losing independence and human agency, when they are told by family they have to give up the keys to the car; Biden was told by his party to give up the keys to the presidency.

It must cut deep; I hope he’s okay.

It’s funny, really, how little attention the news pays to the universal aspects of stories like this. How the immediate reaction focuses on predicting what might happen next, rather than on sitting with what’s just happened. How it refuses to dwell on the humanity, those moments of insufficiency most of us have faced and will continue to face in life.

The news runs away from the lessons of others’ experience, the things we might take and apply in our own lives. And that seems like a shame.

This post was filed under: Media, News and Comment, Politics, BBC News, Joe Biden, Peter Wehner, Reeta Chakrabarti, The Atlantic.