Calmness is key

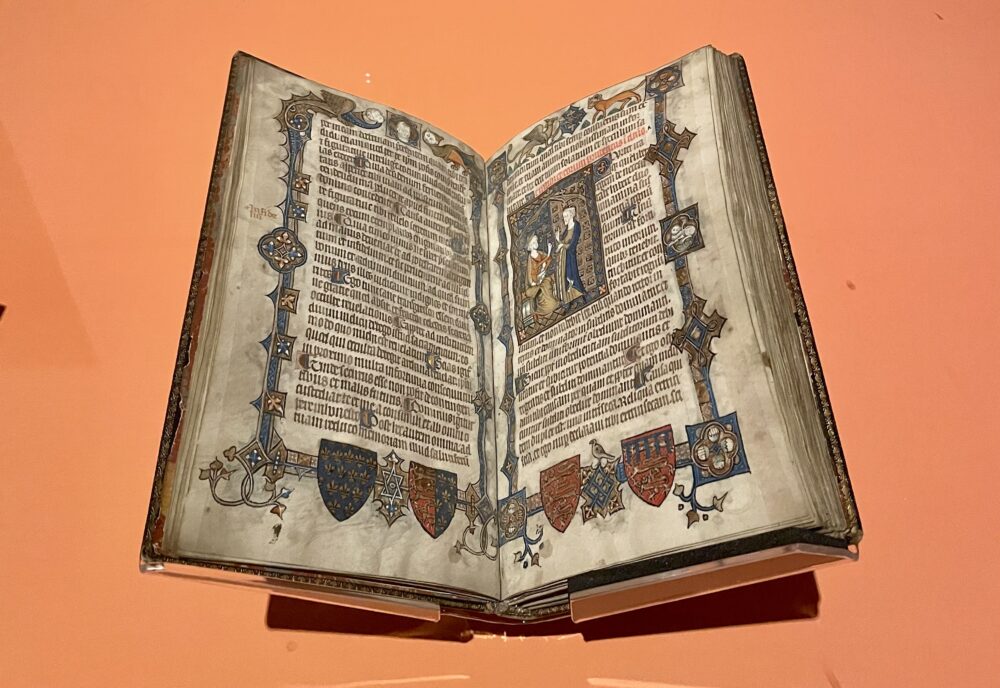

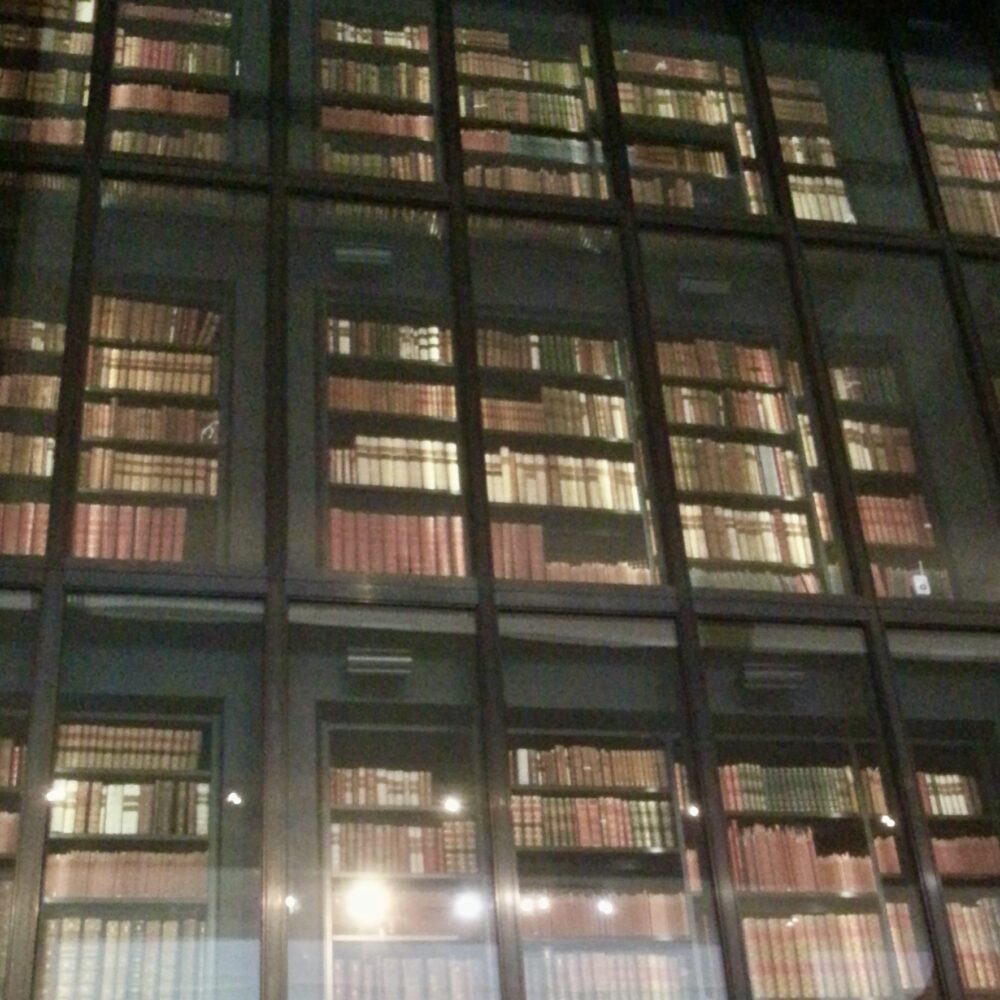

Jonathan Moules recently wrote in the FT about the British Library’s ongoing response to a significant cyber attack. The piece focused on the role of the Chief Executive Officer, Roly Keating.

I have no inside knowledge about what happened at the British Library. It is perfectly plausible that the Library’s public face on the events might not truly reflect the experience of the staff working for the organisation. In addition, the piece is light on accountability for the (assumed) security lapses which led to the attack in the first place. Nevertheless, as a profile of a senior leader responding to an incident, a few things stood out to me.

Firstly, I admired Keating’s calmness. Moules explicitly describes him as ‘calm’ and ‘softly-spoken’, but it was Keating’s declaration that ‘I’m a believer in eight hours’ sleep’ that stood out to me.

When big things happen, it is second nature to panic and rush headlong into responding. The more one panics, the more urgent tasks appear to become. Teams must work ever-increasing hours at an ever-increasing pace until they inevitably burn out. This is a pattern I’ve seen more times in my career than I’d care to count.

The secret to things going well is for the person leading the response to remain calm. This takes considerable training and enormous effort in the moment. It usually requires disappointing people who are panicking: it might mean declining requests for hourly updates from people with every right to ask for them. It often means slowing the response down, acting on the insight that doing the right thing at a medium pace is considerably better than doing the wrong thing quickly. Most of all, it means projecting calmness and control.

Keating says, ‘This was a situation we had thought about, we had rehearsed.’

You can almost hear those words as the opening to the initial ’emergency meeting’ that Keating chaired. It’s easy to understand how they would imbue a sense of calm among those attending. It’s reassurance that, while this situation is unprecedented, it isn’t unexpected. It’s just time to follow the plan.

And that’s the second thing that stood out to me: they had a plan, and more importantly, the person leading the response knew they had a plan, had confidence in it, and followed it. This shouldn’t be surprising, yet it is frighteningly common to find people trying to lead incidents who are either unaware of the plan or disregard it.

Of course, having rehearsed the plan is a great help in enabling a sense of calm, so this is self-reinforcing. Yet, it’s not uncommon to hear of senior leaders who fail to prioritise preparation for unlikely contingencies, thereby shooting themselves in the foot.

The final thing—and it’s hard to know how much of this is down to Moules’s writing—is the clarity of thought in the response. Keating uses plain English in describing ‘an emergency meeting with library executives and the security team’, not some opaque jargon like ‘establishing an incident response cell.’ Moules talks about ‘articulating choices’, not ‘developing an options appraisal’.

It was an article that gave me a little bit of hope.

This post was filed under: News and Comment, British Library, Financial Times, Jonathan Moules, Roly Keating.