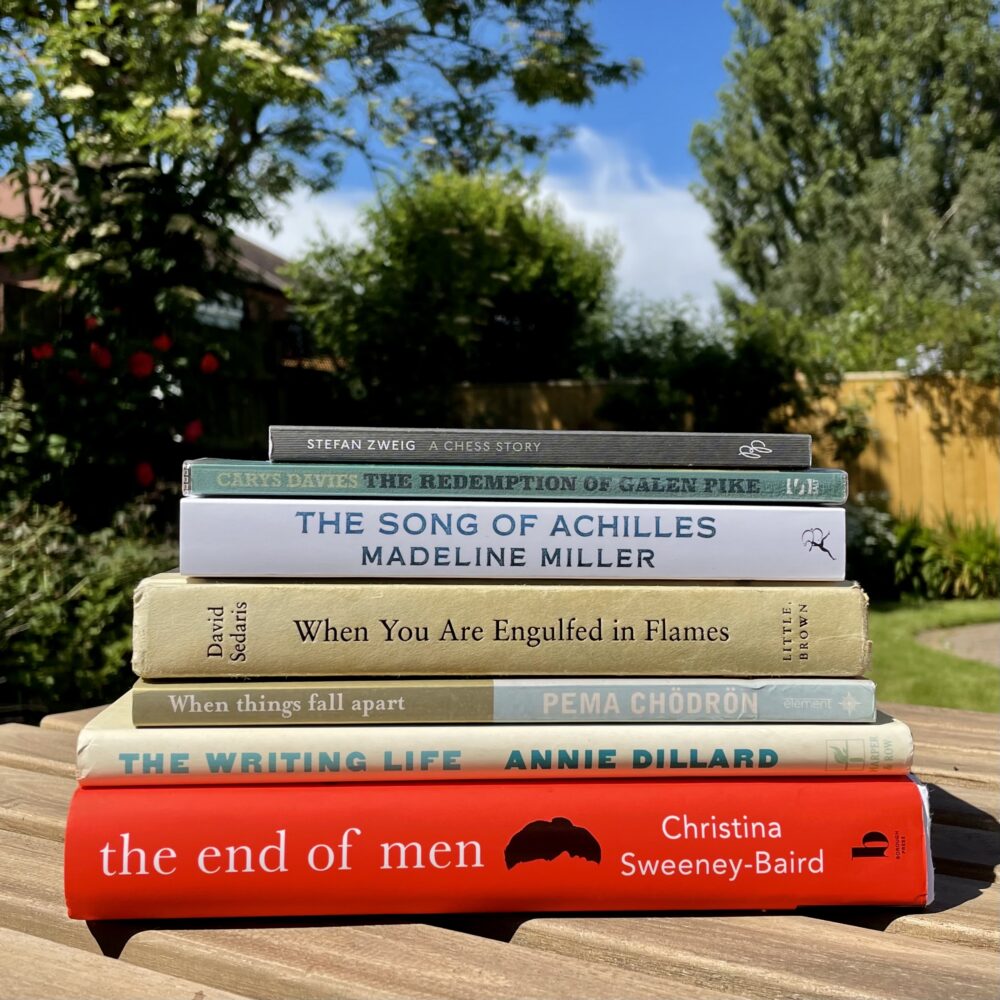

What I’ve been reading this month

This is the sixty-second of these monthly posts about what I’ve been reading, and I’ve got seven books to mention.

A Chess Story by Stefan Zweig

This is Zweig’s 1941 novella, only 80 pages in length, which I read in Alexander Starritt’s 2013 translation. Some translations have been published with the original title The Royal Game, which I think I prefer.

With such a short book, it’s hard to talk much about the plot without giving away key details. The setting is a ship travelling from New York to Buenos Aires. Our narrator discovers that a chess world champion is on board, and a number of matches follow.

Zweig crams more food for thought into 80 pages than most full-length novels. His main theme seems to deal both explicitly and allegorically with Nazism, largely from a psychological perspective. There is a brilliant account of prolonged isolation and it’s psychological effects. And the plot itself moves at a reasonable lick.

This was very easily read in a single sitting, and well worth it.

The End of Men by Christina Sweeney-Baird

My friend Rachael recommended this to me as a book which, despite being very close to home, she’d raced through in a couple of days. Published earlier this year, but written pre-covid, it is a novel set mostly in the UK in the near future concerning a global pandemic. Unlike covid, the pathogen in the book affects only men and has a very high mortality rate.

This was a great recommendation.

The plot and characterisation are, to be honest, a bit bonkers: for example, one of the main characters is an A&E consultant who loves the ‘certainty’ of medicine (is there any specialty that’s less about certainty and more about balancing risk than emergency medicine?) and who changes to a completely different specialty overnight, with no training.

The book has a cast of different narrators, and the vast majority of the narration is by female characters. This is a really inspired creative choice, widening the scope of the novel and focussing on those ‘left behind’, and most of the recurring characters were well fleshed-out. The decision to have the occasional standalone chapters widened the field even further. The gender issue feels like it would have attracted more controversy in reverse, though it’s not like the world is short on books written from a male perspective about the deaths of women.

The choice to include ‘newspaper articles’ as chapters was weakened by deciding that those articles should be first-person narrated, in the same style as every other chapter. The writing throughout struck me as pretty pedestrian.

But you know what? For all its faults, I raced through this book much as Rachael did. It feels wrong to call a book about the deaths of millions “fun”, but it really was. And perhaps even a little cathartic.

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

Published in 2011, this is Madeline Miller’s much-acclaimed retelling of the story of the Trojan War, focused on the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles. It is narrated from the perspective of Patroclus.

My knowledge of Greek mythology isn’t great, though I think I remember a little bit from school. I was a little nervous of reading this despite all the recommendations because I thought it might be a little too fantastical for me, what with all the gods and centaurs and everything… but at its heart, this is a story about the nature of love and courage, and the context was so well realised by the author (helped, no doubt, by centuries of earlier material for which the author has a clear passion) that I didn’t find it to be a barrier.

This was both a thrilling page-turner and a love story, and I enjoyed both equally.

When You Are Engulfed in Flames by David Sedaris

This is Sedaris’s 2008 collection of humorous autobiographical essays, and I was predisposed to enjoy it given that I’ve enjoyed all of his other similar volumes.

This one had a fantastic essay about time spent in a Medical Examiner’s office (‘The Monster Mash’) which brought back memories of my medical school elective spent in a Medical Examiner’s office in Calgary. One of the essays also had some examples of strange English phrases spotted in Japan (‘The Smoking Section’) which made me choke on a drink on public transport, resulting in coughing fit which has become entirely socially unacceptable in the pandemic era.

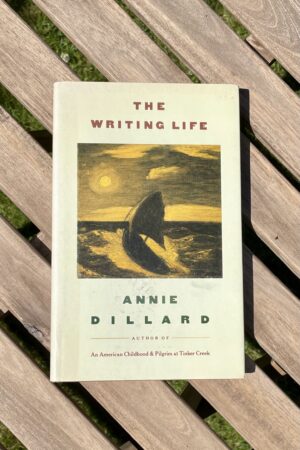

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

This is Annie Dillard’s 1989 collection of short essays on how she writes, and the process of writing in general. I don’t write for a living (obviously), but much of what Dillard says in this book felt familiar from the times when I have done bits of writing here and there, and I enjoyed the deeper insights of such a well-regarded and talented writer.

This was well worth reading considering its short length.

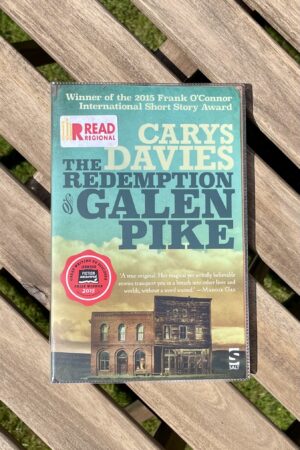

The Redemption of Galen Pike by Carys Davies

Carys Davies’s much-celebrated 2014 collection of seventeen short stories wasn’t really up my street. This isn’t that surprising, and nor should it put you off: I’m not generally a fan of collections of short stories.

The lengths in this collection are highly varied, from a few sentences to thirty or so pages. I didn’t pick up any particular theme running through the collection, though quite a few of the stories contain unexpected twists, and I suppose in retrospect that most of them build up some kind of tension or suspense. I particularly enjoyed the titular story, and also ‘Sybil’, but it was ‘The Quiet’ which was the standout story for me.

However, many of the others in the collection did nothing for me at all, and unfortunately I don’t think that the signal to noise ratio was great enough that I’d want to pick up another of Davies’s collections.

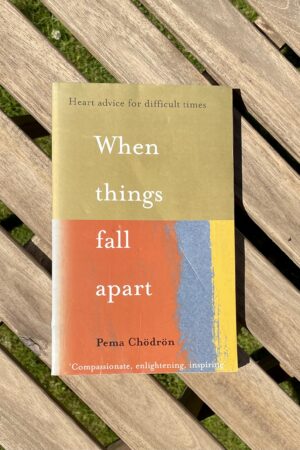

When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön

I picked this book up because I’d heard about it in passing somewhere, and evidently had the wrong end of the stick. I had understood that it was an autobiographical account of personal suffering and challenge and insightful tips on how to cope with life “when things fall apart.” It isn’t really that. First published in 1997, it’s an introduction to several aspects of Buddhist practice, explained in an accessible and relatable way, with lots of personal anecdote thrown in and a warm, caring, personal tone.

While this was interesting and easy to read, I don’t think I would have picked it up had I done my research first, as it’s not really my kind of thing. I won’t be picking up any of Chödrön’s other (many) books—but if this is a topic you want to read about, this book seems like an approachable starting point.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Alexander Starritt, Annie Dillard, Carys Davies, Christina Sweeney-Baird, David Sedaris, Madeline Miller, Pema Chödrön, Stefan Zweig.