I’ve nine books to tell you about for November, some of which were better than others.

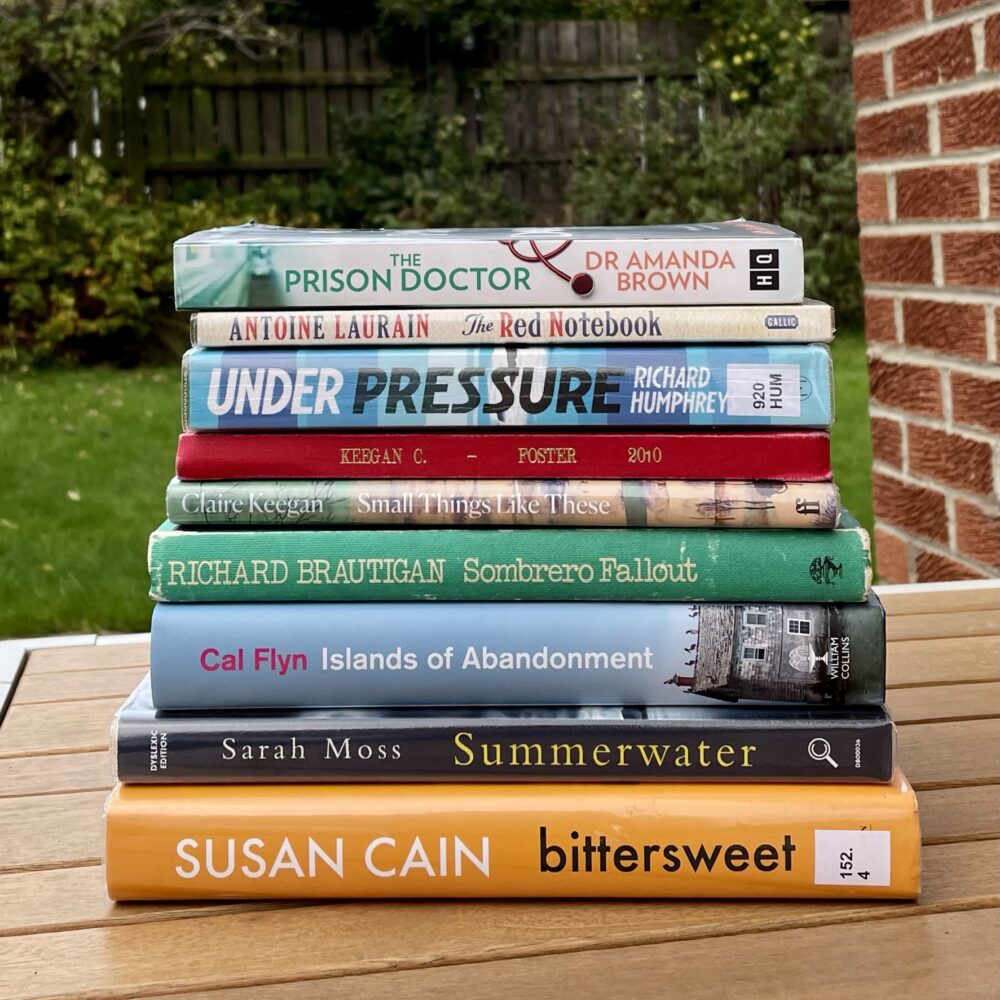

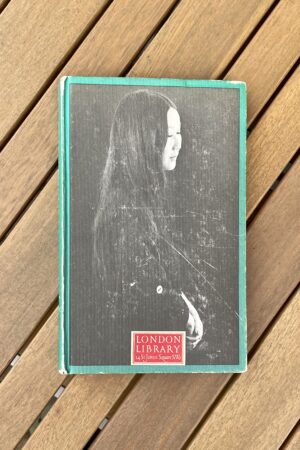

Before picking up this book, I’d never heard of Richard Brautigan, the American author who died the year before I was born. I decided to read this 1976 novel of his after an acquaintance told me that this was the book they used to judge the quality of a bookshop: only shops stocking Sombrero Fallout were worth visiting. I’ve since learned that this is something Jarvis Cocker says in the introduction to the recent Canongate edition, so not quite as quirky and original as I’d imagined.

Yet quirky and original this short novel certainly is, one of the most singular and enjoyable books I’ve read this year. The eccentric plot concerns an American humorist who has recently split up from his Japanese girlfriend. He starts a new absurd story about a sombrero falling from the sky in a small American town, but discards it after a few paragraphs. However, the story takes on an increasingly preposterous life of its own within the waste paper basket. The book interleaves this developing story with chapters about the humorist and chapters about the Japanese girlfriend. The chapters are rarely longer than a couple of pages, and frequently much shorter.

The writing is surreal and very funny. Brautigan makes some quotable and yet delicate observations about the nature of life, love, longing, and loss. The overall effect is utterly beguiling.

There is something about Brautigan’s writing in this book that reminds me of Italo Calvino, whose worked I loved. I’ll be seeking more.

With thanks to The London Library for lending me a copy.

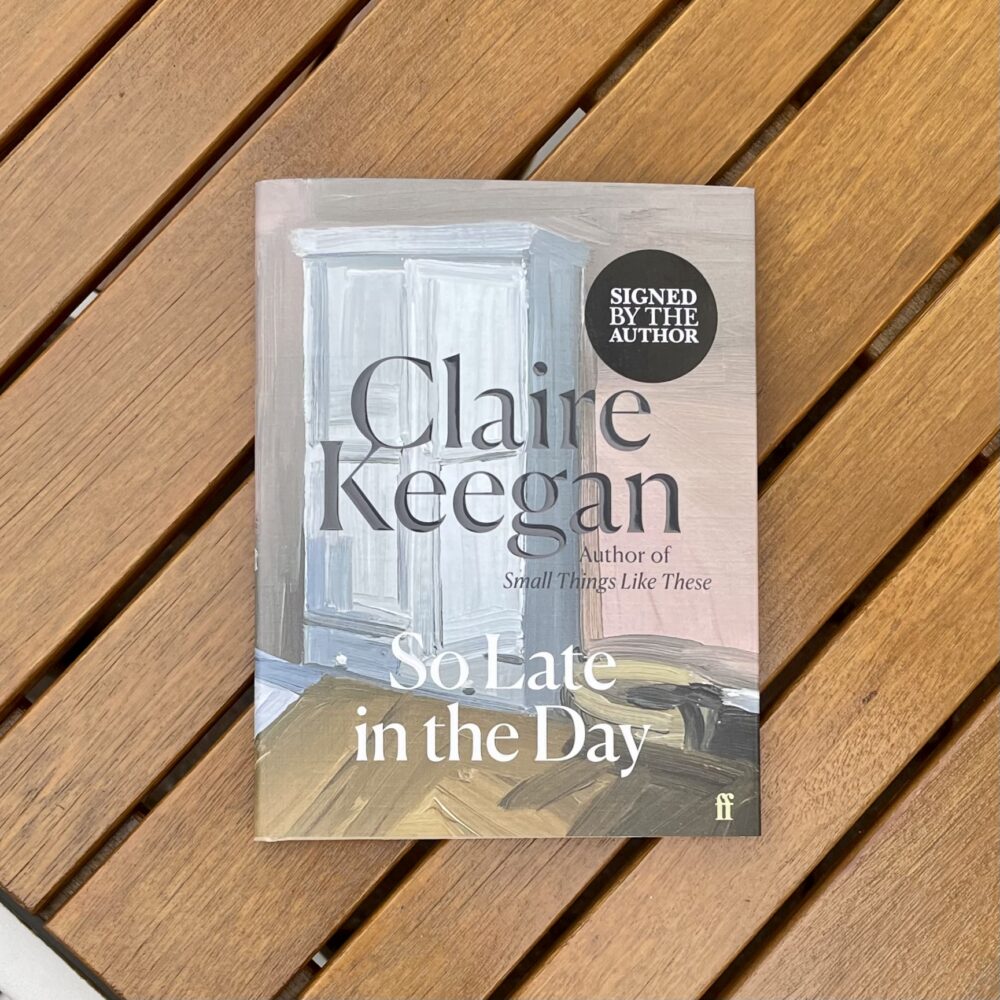

My sole reason for picking this up was the Booker prize long-listing. Being nominated for a Booker doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll enjoy a book. But, with a book as short as this, and one with themes of ‘compassion’ and a ‘stern rebuke of sins committed in the name of religion’—the sort of thing that’s right up my street—it seemed worth giving it a go. I’m glad I did.

This short book was brilliant. It’s about morality, and in particular the contrast between the morality of the ordinary person contrasted with the morality of the Catholic Church. It excoriates the latter for its treatment of unmarried women.

The novel is mostly set at Christmas, in 1986, in Ireland. The central character is a coal merchant with a wife and five daughters. He knows that he could have expected much less as the son of an unmarried servant, especially one whose mother died young. His own experiences and moral attitudes are brought into sharp contrast with those of the local convent and Magdalen laundry after an experience while making a coal delivery.

The style of writing is beautifully concise and precise, and the novel as a whole packs a punch far beyond that which its page-count would suggest.

I will definitely be seeking more of Keegan’s work.

With thanks to Newcastle Libraries for lending me a copy.

This much-recommended book by the Scottish investigative journalist, published in 2021, examines areas of the world which have been abandoned by humans for a wide variety of reasons. From this, she tries to imagine the future of Earth post-humanity (or as Flyn sometimes proposes, after the ‘mammalian era’), and also tries to understand how the end of humanity might arrive.

This sounds terribly depressing, but this is actually a book rooted in hope and beauty, celebrating the power of nature to rebound and adapt. There’s also a fair about of interesting public health stuff in Flyn’s discussion: I was particularly struck by her understanding that after the Chernobyl disaster,

Overall, poverty-linked ‘lifestyle diseases’ and poor mental health pose a far greater threat to affected communities than radiation exposure.

I also especially liked this line from her conclusion, which crystallised many vague thoughts I’d had while reading:

Faith, in the end, is what environmentalism boils down to. Faith in the possibility of change, the prospect of a better future – for green shoots from the rubble, fresh water in the desert. And our faith is often tested.

This was beautifully written, hopeful, and taught me a lot that I didn’t previously know on a whole gamut of topics, from supervolcanoes to how feral cows behave. It was superb.

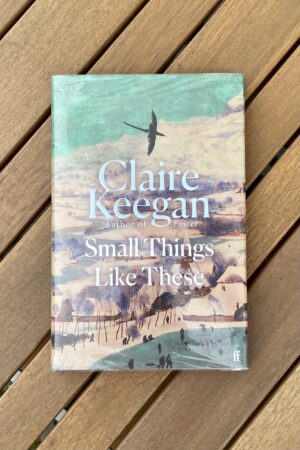

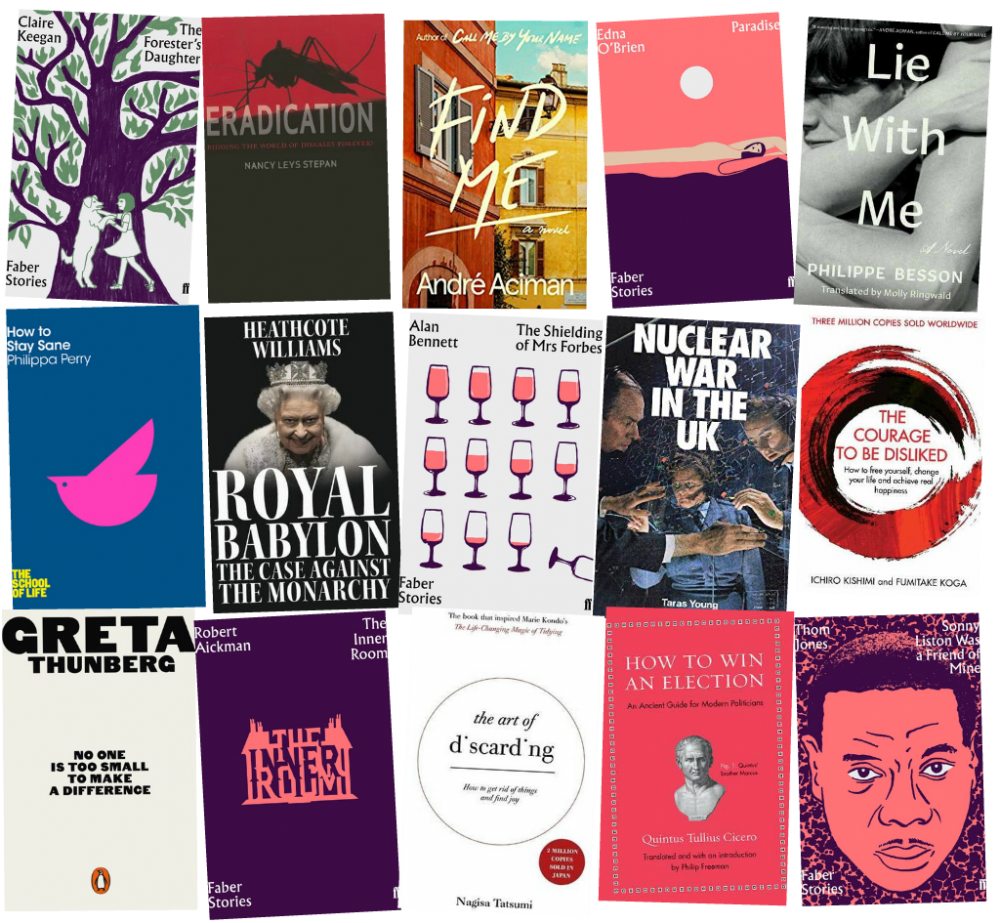

Foster by Claire Keegan

I picked this up as a result of enjoying Small Things Like These by the same author. It’s another very slim, single-sitting novel set in Ireland which explores societal themes. In this case, the main theme is family.

A young girl is sent from her large, struggling family to stay with foster parents for a few months. We see, through the eyes of the child, the differences between the two family settings, and watch as—over the course of a few short months—she grows and matures.

Like the other novel, this is beautifully written with precise language, the author clearly having weighed every word. The plot here is simple and unremarkable, but Keegan’s eye for detail and realism turn it into something extraordinary.

I think I enjoyed Small Things Like These a dash more, but perhaps that’s only because I read it first and so Keegan’s remarkable style was new to me. Foster is definitely to be recommended, too.

With thanks to The London Library for lending me a copy.

This 2019 memoir of serving onboard a Polaris nuclear submarine has been on my ‘to read’ list since it was published. It was pure prejudice that meant that it languished on the list: I imagined it was going to be an interesting account of an unusual occupation, but probably written from the exhausting point of view of a navy-lifer with a proselytising view of military service. I was wrong.

Humphreys’s account of his training and subsequent service was illuminating and insightful. His reflections on his mental health, and that of fellow servicemen, particularly in the context of unacceptable bullying and humiliating behaviour from those higher up the chain of command are arresting.

Humphreys also writes elegantly about the philosophical aspects of serving on a nuclear submarine, and the duty to carry out actions which would almost certainly lead to the end of humanity. These are fascinating debates in the abstract, but Humphreys personal experience offers a unique, novel perspective.

I never imagined I’d race through any memoir of military service, but this had me hooked.

With thanks to Newcastle Libraries for lending me a copy.

I chose to read this short novel, published in 2020, because I previously enjoyed Moss’s Ghost Wall. Summerwater is a similarly atmospheric novel, and I think perhaps I enjoyed it slightly more.

The novel is set on a single rainy day on a Scottish caravan park, near a loch. Each chapter follows a different character staying on the park. While each narrative occasionally mentions the other characters and groups, the whole ‘population’ doesn’t come together until the final section. Between each of the chapters is a short section of writing about the surrounding natural world.

Moss’s crisp writing evokes a claustrophobic, oppressive, tense atmosphere, that somehow also felt entirely relatable.

I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that the final five words, as ordinary as they are, sent chills down my spine and will stay with me for a long time.

With thanks to Newcastle Libraries for lending me a copy.

This memoir of a GP’s decision to leave her village surgery and pursue a career in prison medicine has been on my ‘to read’ list since it was published. I put off reading it for a few years because too much of my health protection day job had come to involve prison outbreaks, so I thought it might be too close to home. Two sequels have been published in the meantime, which gives some idea of the book’s commercial success.

The book has three parts: the first covers Brown’s decision to leave general practice, and—in some ways—I found this the most interesting section. Although the change was different, the process and feelings Brown described reminded me of my experiences of moving from hospital medicine into public health. The second section discusses Brown’s early prison career in young offender institutes and men’s prisons, including clinical stories of some prisoners alongside her training and career development. The last section concentrates on her time working in a women’s prison, and concentrates almost exclusively on the clinical vignettes.

I was left with mixed feelings. The book had a certain ‘fictive sheen’, with events and stories feeling neatly contained and complete in a way that’s rarely true in medicine. I’m convinced this is a consequence of changing details to anonymise cases and perhaps creating compound characters, but it just felt a little false. The dialogue also felt awkwardly written, without any ring of authenticity.

On the other hand, this neatness of story and writing made this an effortless read, and Brown and Kelly still gave interesting illustrated insights into the lives of prison medics and their patients… so maybe the slightly ‘glossy’ writing is worth it.

This 2014 French novel was translated by Emily Boyce and Jane Aitken, two of the three translators of Laurain’s The President’s Hat, which I previously enjoyed.

This novel is in the long tradition of blind love stories. A woman is mugged and left in a coma. A man finds her discarded handbag and, using its contents, tracks her down and falls in love with her, without ever having met her.

I found this a bit inauthentic and twee. It has the warm tome of The President’s Hat, but is a little too humdrum and unimaginative to have the same charm. The plot was too predictable to be truly engaging, and the behaviour of the central character seemed to me to cross the line into being creepy rather than romantic.

With thanks to Newcastle Libraries for lending me a copy.

I have long had a theory that melancholy is under-appreciated in modern British society. I feel especially strongly about this in connection with Christmas. I think Christmas is naturally a time which combines happiness and melancholy, but increasingly, the infantilisation of British society sees it treated exclusively with childlike chirpiness.

All of this led me to believe that I’d find much to enjoy in Bittersweet, Susan Cain’s recent book on the place of sorrow and longing in society, especially as I’d enjoyed her previous book, Quiet.

However, I was a bit disappointed. This felt too focused specifically on American cultural norms for me as a British reader, and it felt focused on a particularly narrow slice even of that society. It felt like there was a certain credulity in the author’s quoting of messages shared on retreats and at narrowly focused conferences.

Bittersweet felt like a memoir of a personal journey into understanding various broadly New Age concepts, presented as popular science—and as a result, it just wasn’t up my street.

With thanks to Newcastle Libraries for lending me a copy.