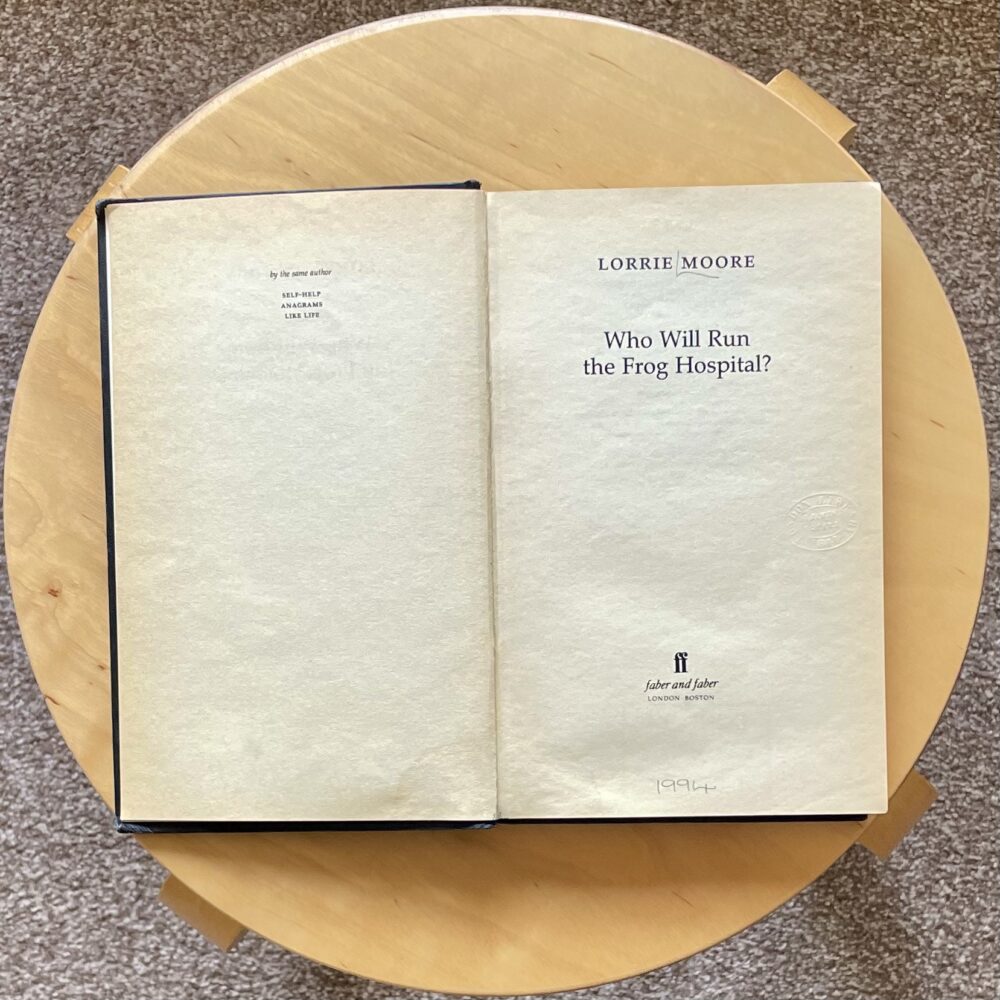

‘Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?’ by Lorrie Moore

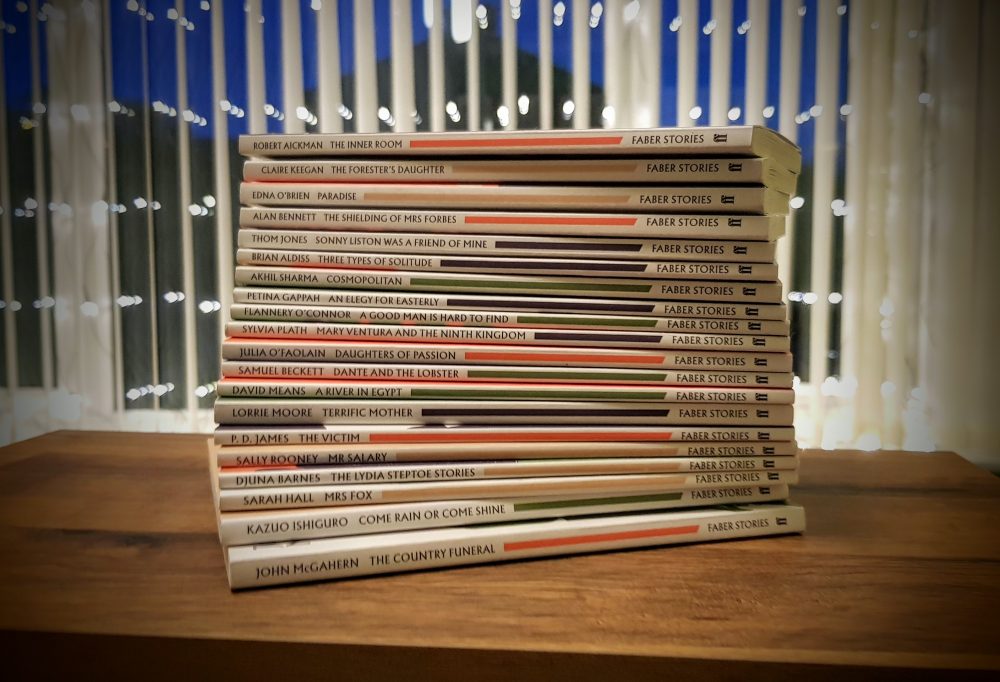

This short 1994 novel has been on my ‘to read’ list for a very long time. I think the ‘quirky’ title slightly put me off; I perhaps expected something consciously ‘different’ and ‘off beat’ that I was never quite in the mood for. I’m not sure why I made that assumption, especially given that I previously enjoyed Lorrie Moore’s Terrific Mother.

This is a much quieter, simpler and brilliant story than I had imagined. This is a novel, like many novels, about how memory is a complicated thing and how we change throughout the course of our lives. It also has some interesting observations on life in small town America, where the narrator grew up, and city life, which particularly comes across in a section featuring a school reunion.

The narrator of this book is a grown woman, Berie, looking back on her teenage childhood and, in particular, her relationship with her best friend Sils. The majority of the novel is set in childhood in the early 1970s, but there are some sections in the narrator’s present day.

Berie and Sils both have part time jobs at a local amusement park, which provides the backdrop to a good portion of the novel. Without spoiling too much of the plot, both the adult narrator, and the child of her recollection, seem a little lost—as though they are searching for meaning and purpose. There’s a sardonic humour throughout which reminded me of My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh.

The blurb says that this ‘is a poignant and evocative novel that will transport readers back to the carefree summers of their own girlhood.’ I obviously don’t have a girlhood to be transported back to, but I’m not sure that nostalgia for childhood is really a gendered issue. I very much enjoyed this beautifully written novel, and think that there’s a lot to like here, regardless of the gender identity of the reader.

Some passages I highlighted:

In his iconic way our father remained very much ours. And in the long shadows of his neglect, we fashioned our own selves, quietly improvised our own rules, as kids did in America, in the fatherless fifties and sixties. Which was probably why children of that time, when they grew up, turned out to be such a shock to their parents.

I remember thinking that once there had been a time when women died of brain fevers caught from the prick of their hat pins, and that still, after all this time, it was hard being a girl, lugging around these bodies that were never right – wounds that needed fixing, heads that needed hats, corrections, corrections.

There were three cellos in the house; one had belonged to my grandfather. The other two belonged to my grandmother, who often gave lessons in town, and whenever we visited she got out one of the cellos and played a piece for us, while we sat on one of the davenports, squirming and pinching each other when she couldn’t see. Later, when I was older, I realized how beautifully she played. But when I was little most of the interest such an event held for me was in watching such a formal woman – ‘a true Victorian lady,’ as my father worshipfully described her – place this large woman-shaped object between her legs and hold it there with her knees, her finger vibrating along the neck in an insectlike movement up and down, the bow in a slow saw across the strings, angling this way or that, gently, to find the note. My grandmother always gazed down upon her cello, like the Holy Mother upon the Holy Child, or perhaps like one woman beholding another at her knees.

For a while I was still telling my flat-chested jokes. But as my own breasts grew larger, so did the disjunction between my body and my jokes, and when I would tell them to people they would look at me funny. I was in a time warp. My breasts had become larger – they were large! – and I was still referring to them as mosquito bites. For a semester, an embarrassing, amphibious semester when I didn’t know who I was, what I looked like, what jokes to tell, moving from water to land, I tried to stop telling any jokes at all. I waited until I’d accumulated enough amusing lines about having big breasts, armed myself with enough invented descriptions, amassed enough self-deprecating remarks about top-heaviness – knockers, blimps, hooters, bazooms – to get me through a party, and then I told those. Getting stuck in elevators, toppling forward, not being able to see the forest for the cleavage.

Now, returning to Horsehearts, I realized, I no longer knew what sweetness was. By comparison to what I found there, I had become sour, mean, sophisticated. I no longer knew niceness, was no longer on a daily basis with it. I no longer met nice people, I met witty, hard, capable, successful, dramatic. Some vulnerable. Some insecure. But not nice, the way Sils was nice. She was nice the way I had long imagined I still was, but then on seeing her again – strangely shy before me but illumined and grinning, as ever, her voice in gentle girlish tones I never heard anymore – instantly knew I was no longer.

We sat in lawn chairs, drying in the sun, and smoked quietly, with Randi, who seemed just the same as always except that, recovered from her Mary Kay days, she had changed her named to Travis, which she’d written on her name tag, with Randi in parentheses underneath. (Could one do that? Could one put one’s whole past, the fact of its boring turbulence, in parentheses like that?)

To go from turmoil to tranquility is excellent for music. To go from an iniquitous den to a practice room is a respite given to us by God.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Lorrie Moore.