In 2005, I was just starting to be released onto the wards in the third year of my medical degree. One of the dullest weeks focused on orthopaedic surgery. The operations were life-changing for the patients but struck me as a sterile version of Meccano. The techniques were ingenious, but their application to a conveyor belt of patients felt depressingly repetitious. Give me a knotty, intractable problem to tilt at (and fail to solve) any day.

The specialty wasn’t right for me, and I wasn’t right for the specialty: I have neither the ego nor the bravado to be an orthopaedic surgeon. I sincerely hope things have moved on in the past two decades, but the male orthopaedic surgeons’ changing rooms were Lynx-Africa, Page-3, clothing-on-the-floor hellholes ripped from straight from a sleazy gym. No thanks.

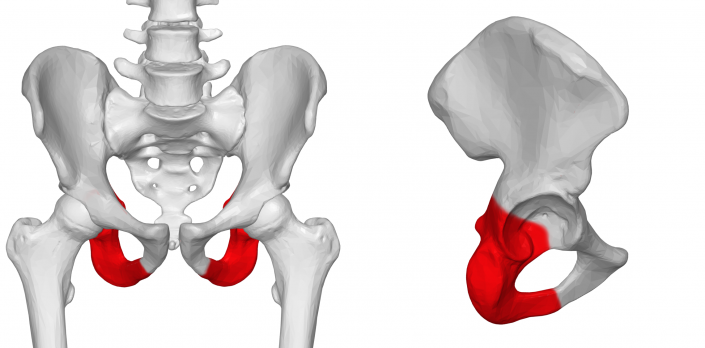

My over-riding memory of that week, though, is not the surgery: it’s a specific patient. She was in her late 80s, she lived alone, and she was fiercely independent. She had never married and was proud of the fact: woe betide anyone who prefixed her surname name with ‘missus’. She had fallen a couple of years previously and broken her hip. She was in hospital because, unfortunately, the nail which was holding her femur together had fractured following another fall.

I met her shortly after her admission, when I was allocated to her to practice my history-taking and examination skills. We fell into a long chat about her fascinating career, an area of work I knew (and know) nothing about.

One thing she was keen to tell me was how ‘miraculous’ the NHS was. She grew up in a poor household. She talked about her experience of TB in her youth, and of being isolated in a charitable sanatorium with no contact with her family for months on end. She talked movingly about one of her younger brothers becoming very unwell when she was a teenager, her parents being unable to afford to call a doctor and having instead to seek help from the church. Her brother died, having never seen a medic.

I remember going with the occupational therapy team to see this lady’s house: a standard part of their practice to see what home aids she might require, or what trip hazards might be lying around. The house was immaculate, not a thing out of place. I could scarcely believe that someone in their late 80s could keep a house so beautifully.

Her surgery turned out to be more complicated than was initially expected. The broken nail proved difficult to remove—by virtue of being broken, it couldn’t just be cleanly pulled out of the hole it had been driven into. Once it had been quite traumatically extracted, the patient required a plate to be screwed in to hold her femur together, with something like a dozen screws. It wasn’t a light undertaking, and this lady ended up spending quite some time in intensive care.

By rights, my story should end there: I moved onto other training weeks. But I kept popping back to see this lady. Every time I saw her, without fail, she talked about the ‘miracle’ of the NHS. She talked about how, when it was first introduced in her twenties, people were terrified to call a doctor as they couldn’t believe there would be no bill. It took a long time and countless leaflets and word-of-mouth until people really trusted that they could use the service. She talked more eloquently than I ever could about how it transformed the life chances of those around her: how gradually, over time, illness came to lose its life-changing significance, and became more of an irritation than a life event. She lamented the loss of her brother.

She talked, too, about her concern for the future of the NHS. She thought that those who hadn’t lived without it didn’t appreciate it. For some reason or other, NHS waiting lists were in the news at the time. She saved a newspaper clipping for me, and when I went to visit, remonstrated with me: why did these people not realise how lucky they were to be on a waiting list for free care? Would they complain if they were on a waiting list to win the lottery? People won’t realise what they’ve got until it’s taken away again.

Over the course of about six weeks, her tenacity and drive—plus support from nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and pain management specialists—resulted in a truly astounding recovery. My last memory of her is of her being wheeled off the ward—backwards, for some reason—with a massive grin on her face, arms waving in the air, thanking everyone she passed (even the other patients). Remarkably, she was going back to her own home, to continue living independently.

Clare Gerada, the president of the Royal College of GPs, once wrote:

One cannot see patients, day in day out for years, without being profoundly affected by this experience and the struggles we witness. Even now, as I write this chapter, I see the faces of my patients and hear their words, some long deceased. I see their ghosts as I walk my dog, shop in the supermarket or walk past their old homes. Many of my patients still live in my mind.

I agree, and today—the 75th anniversary of that day in 1948 that this patient remembered so well—this patient is making her unique presence very well known to me.

Of course, her reflections aren’t really about the NHS as it is currently structured: her point is about the value of care which is free at the point of use, funded through general taxation. Politicians like to politic about the specifics: organisational structures, social insurance models, completely free care versus co-pay models, the level of involvement of the private sector. At it’s founding, NHS hospitals were made into a single organisation. These days, there are countless separate organisations, many operating in competition with one another, mostly on the basis of finance rather than quality of patient care.

But sometimes, and particularly on an anniversary like this, it’s worth taking a step back and realising what we’ve got: the NHS is a miracle. We shouldn’t forget that it wasn’t always like this, and won’t necessarily be like this forever.

The NHS is under extreme pressure at the moment: it feels like it’s falling apart in front of our eyes. But at least we still have an NHS which strives to deliver its founding principles. Sadly, these days, political rhetoric around the NHS has become entirely about patching it up, about making it live within its means—as though those means are not entirely determined by us.

How wonderful would it be if we used the 75th anniversary to invent the same thing for social care? To have the vision to say “the whole of society will take the risk” instead of the individual? To proceed with visionary boldness to meet the need, not balance-sheet-driven timidity. To prioritise compassion over efficiency.

My birthday wish for the NHS is that, perhaps, we’ll have moved in that direction before it reaches its century.

- We don’t have completely free care in England: there are prescription charges, dental charges, optical charges, and so on and so forth.

The image at the top of this post was generated by Midjourney.