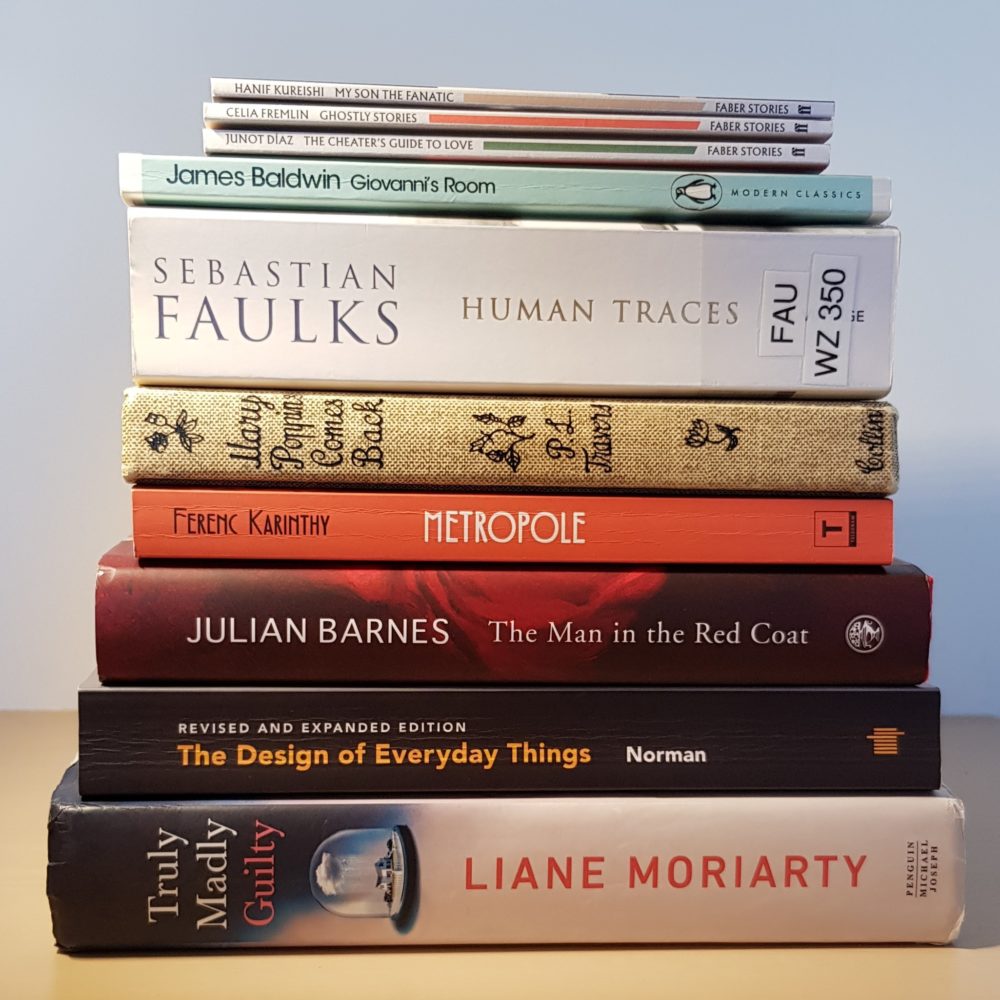

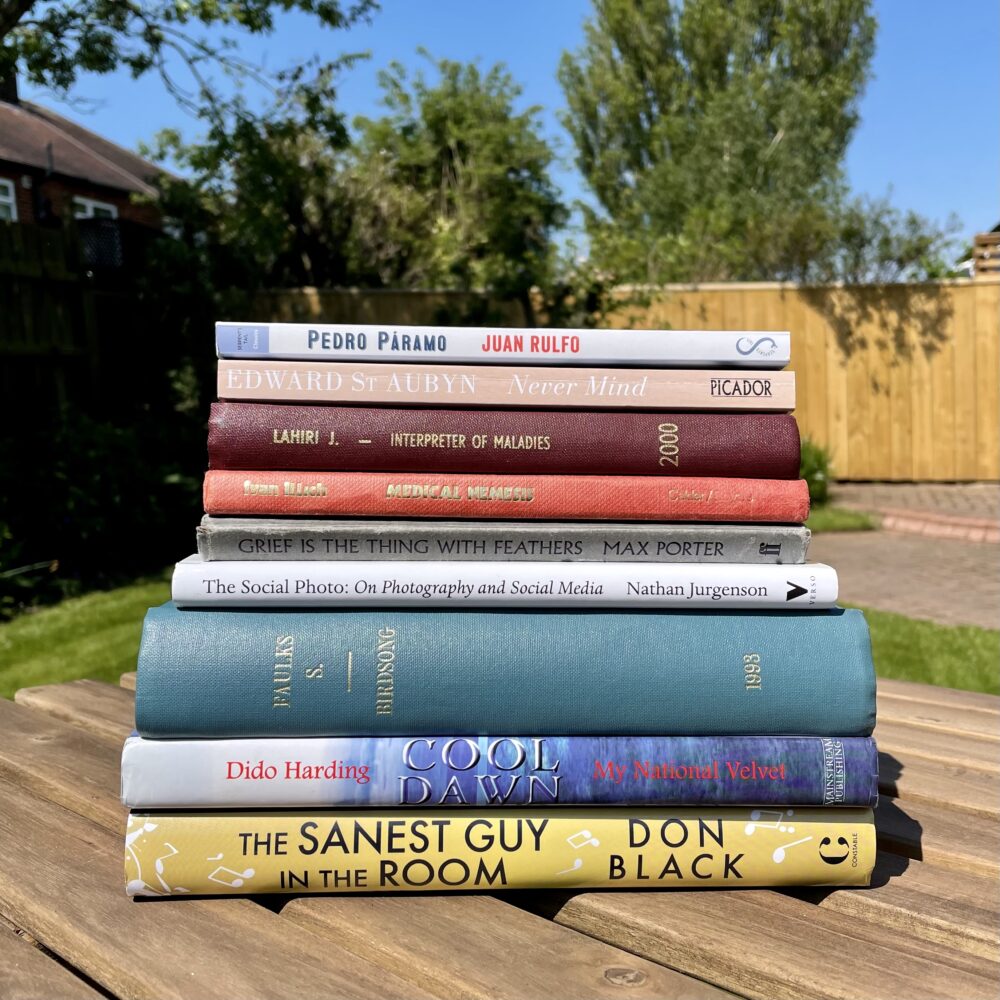

What I’ve been reading this month

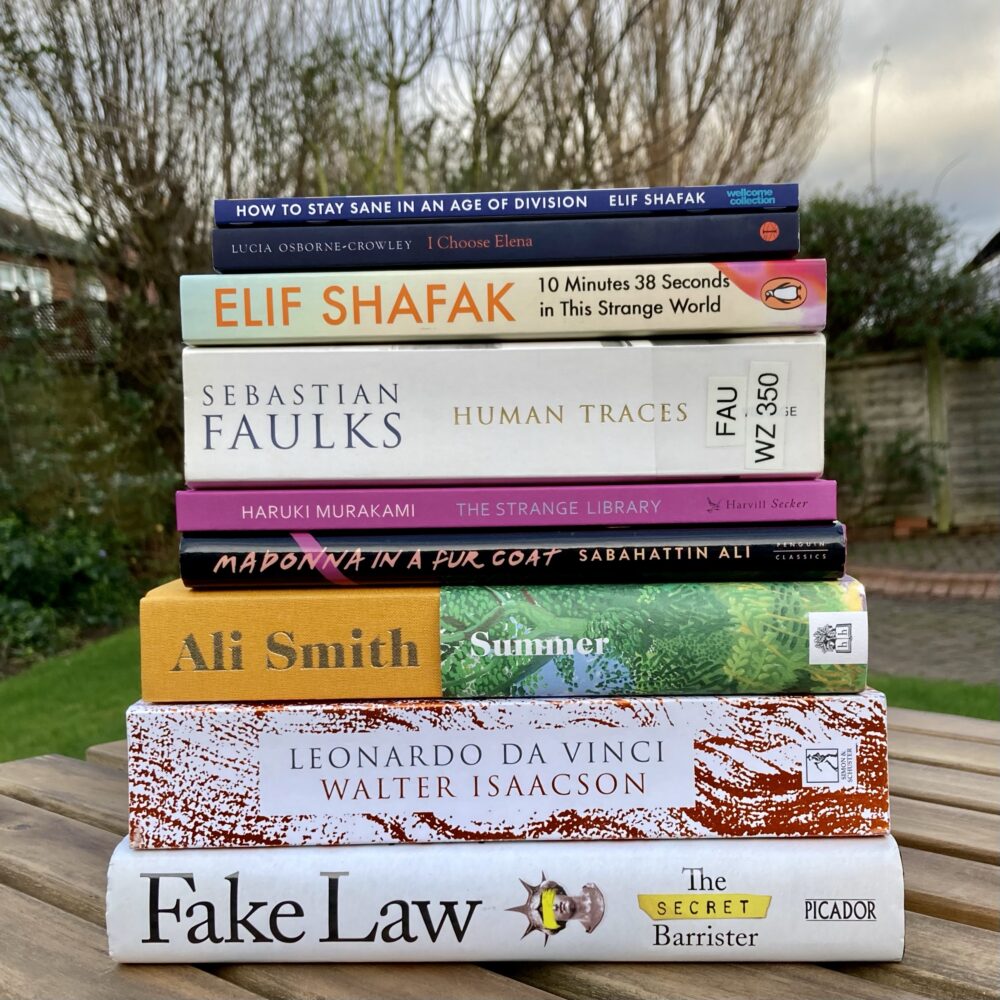

May has been one of those months where it feels like I haven’t read very much at all, until I come to write this post and realise I’ve racked up nine books… of variable quality.

Medical Nemesis by Ivan Illich

I dug this 1976 book out of the library in response to my Goodreads friend Richard Smith re-posting his 2002 piece about it. I’d never heard of it before, but blimey its force of argument blew me away.

Illich’s central argument is that “the medical establishment has become a major threat to health … A vast amount of contemporary clinical care is incidental to the curing of disease, but the damage done by medicine to the health of individuals and populations is very significant.”

Some of the specific arguments and statistics Illich uses show their age, but it is hard to substantially disagree with most of his central points. Illich’s lengthy arguments about the various forms of iatrogenic harm lead him to argue for keeping most of the population away from the medical establishment and instead bolstering the ability of communities to maintain their health and cope with ill-health. “The level of public health corresponds to the degree to which the means and responsibility for coping with illness are distributed among the total population … A world of optimal and widespread health is obviously a world of minimal and only occasional medical intervention. Healthy people are those who live in healthy homes on a healthy diet in an environment equally fit for birth, growth, work, healing, and dying.”

For me personally, this book has come at the perfect time. I have been worrying about the extent to which the response to the covid-19 pandemic has emphasised a professional / medical model of healthcare to an extent that I have never before seen in my medical career. Even at the ‘slightest symptom’ the population is encouraged to engage with the ‘establishment’ via formal testing. I worry that we will struggle to put the genie back in the bottle.

The age-adjusted mortality rate for the most deprived quintile of the UK is a multiple of that for the least deprived quintile, yet—at least from what we have heard to date—the mainstay of the plan for future pandemics appears to be to beef up the medically driven response (people like me) rather than doing anything meaningful to tackle the underlying social issues.

This book was a timely reminder of the limits of the medical approach to health that articulated much of what I’ve been worrying about. I’m not sure I would go as far as Illich in arguing against medicine, but having a polemic like this certainly stimulates thought.

Interpreter of Maladies by by Jhumpa Lahiri

This is Jhumpa Lahiri’s debut collection of nine short stories of about 20 pages each about experiences resulting from a meeting of Indian and (mostly) American culture. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2000.

I picked it up mostly on a whim because I fancied reading some short stories and this caught my eye, and I’ve ended up very much enjoying it. I liked every one of the nine stories, and found them all engaging and surprisingly powerful. Lhari grounds each of the stories in everyday life, and the power comes from the close observation of common experiences. The prose style feels spare, simple and exact.

I also felt that I gained new insight into what it is like to be a cultural outsider on a day-to-day level, and the internal conflicts and misunderstandings it can create. This element of the book felt relevant and current.

I’d certainly recommend this one.

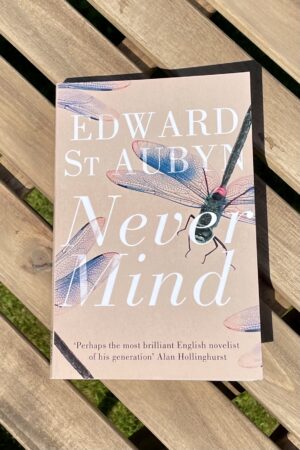

Never Mind by Edward St Aubyn

I’ve read a lot of praise for the Patrick Melrose series recently, so thought I would give it a ago. This first book, published in 1992, introduces Patrick as a five-year-old. Set over a single day in Provence, it follows his parents and their friends as they prepare for a dinner party.

It is a book of layers. It presents with great humour Patrick’s absurd aristocratic cruelty borne of a deeply held sense of entitlement and privilege. At the same time, it shows us the deviating impact of that attitude to life, piercing the idea that eccentric cruelty is harmless and tolerable.

This may have been written decades ago, but it feels highly relevant in the current political context, where we’re perhaps beginning to see a greater awareness of the dangers of allowing those with great privilege to act in ways which aren’t generally acceptable. We perhaps shouldn’t be so forgiving of the ‘bumbling toff’ stereotype which so often masks a local of morality.

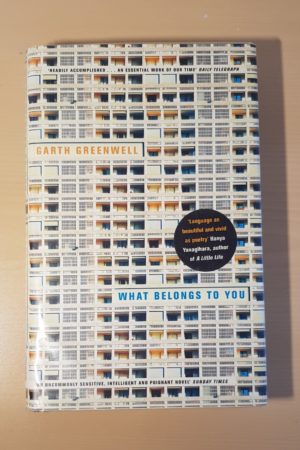

Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks

I’m not usually a fan of war novels, but having loved Human Traces last year, I thought I’d give Faulks’s most famous novel a try.

Birdsong was first published in 1993, and follows two main characters: Stephen, who we first meet in 1910 and later follow through the misery of the front line in the First World War, and his granddaughter Elizabeth, who we meet in 1978 as she tries to research her grandfather’s past. The novel jumps about between these time periods across seven sections.

The main themes of the novel were love (romantic and otherwise) and trauma, and the impossibility of truly understanding a person’s own experience of either of those things from a distance. We can never truly know what another person has experienced, and the distance of time from historical events makes understanding ever more difficult.

I thought this was a brilliant novel, and one with a lot of layers to it. It was a book in which the plot would draw me in, and I’d find myself reflecting on some of the deeper insights hours later: I’m not sure the plot will last as long in my memory as those insights and reflections.

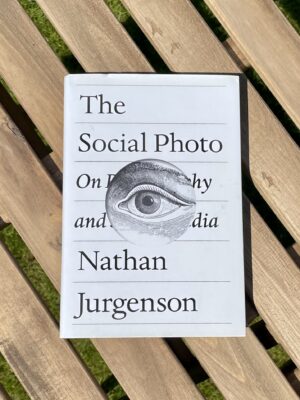

The Social Photo by Nathan Jurgenson

I thoroughly enjoyed this essay by Nathan Jurgenson, published in 2019. It is in two parts.

The first part considers the way in which the nature of photography has changed in recent times, with the vast majority of photos taken today being intended as communications forming a specific part of conversations, rather than as images designed to stand on their own merit. Jurgenson made these point through a lively account of the history of photography, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

The second part was more wide-ranging. While still based primarily around photography, it considered broad questions about the impact of social media on society and our behaviour. As Jurgenson acknowledges, there are a lot of books which cover this ground, often from clear pre-conceived positions (for example, arguing for ‘digital detoxes’). Jurgenson’s treatment is much more balanced and insightful, and makes a good argument that even when we are away from social media, it has altered our social behaviour to such an extent that there really isn’t a hard offline/online border of the type others try to describe. I found this a strong and convincing argument, albeit one that I wasn’t really expect this book to cover.

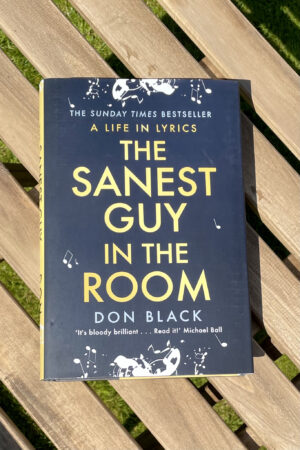

The Sanest Guy in the Room by Don Black

Published last year, this is the autobiography of the lyricist Don Black.

“I have never been a fan of autobiographies,” he says in the very first paragraph, justifying his decision to concentrate on interesting anecdotes spanning both his career and his 60-year marriage. This results in a book that’s quite light in tone, but an awful lot of fun.

There are—as you might expect—a lot of lyrics in the book, which only served to remind me quite how diverse Black’s career in lyrics has been.

Grief is the Thing With Feathers by Max Porter

Grief is the Thing with Feathers is Max Porter’s exceptionally popular 2015 essay, which combines prose and poetry, fantastical allegory and deep reflection, to discuss the process of grieving. The book centres on a family of four who are bereft by the untimely death of the mother, and are helped through their grief by a crow.

Some of Porter’s writing and close observations in this short book are brilliant, but I don’t really rate the totality of the book. It just isn’t really up my streeet: a bit to abstract (and at times confusing) and a bit too fantastical for my taste. But your mileage may vary, as they say.

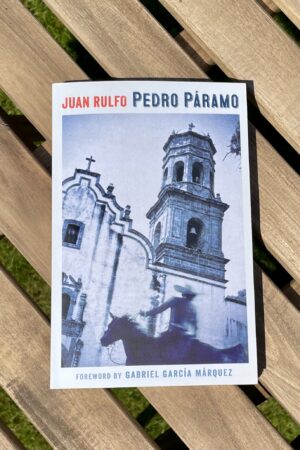

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo

First published in 1955, some consider this to be one of the great works of 20th century literature. I read the 1993 English translation by Margaret Sayers Peden.

The narrative is split across 68 short dream-like fragments in which the title characters searches for his father following the death of his mother. It’s never quite clear what is real and what is hallucination, who is alive and who is dead. I enjoyed this for about the first half of the book, then started to get increasingly frustrated by the structure.

I’ve no doubt this book has a lot to offer, and it is reputed to be quite beautiful in its original Spanish, but I’m not sure it has quite the same amount to offer a casual reader of the English translation.

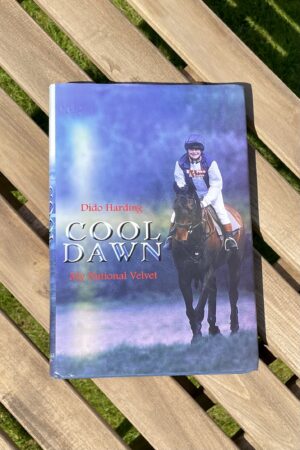

Cool Dawn by Dido Harding

Published in 1999, this is Dido Harding’s book about her favourite horse, Cool Dawn. I am not the target audience for this book: it’s very clearly aimed at the hunting / racing set, and I know very little of either, making this my least favourite book of the year so far by a furlong.

Most of the book is made up of descriptions of horse races, which held little interest for me. The bits in between, about the practicalities of owning a race horse, were more interesting, but felt emotionally flat to me. I struggle to empathise with the apparent emotional turmoil of being on a family skiing holiday in Canada while the horse I own is undergoing intensive physiotherapy for a trapped nerve back in England. Perhaps that’s not surprising given that the very existence of horse physiotherapy was news to me.

Similarly, the lack of reflection on the ethics of horse racing and hunting surprised me, but I think that reflect my naivety more than the book itself. Injuries seem to be considered more from the impact of the racing life / financial impact than concern for the welfare of the animals, which feels callous to me but is presumably the reality of the lifestyle

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Dido Harding, Don Black, Edward St Aubyn, Ivan Illich, Jhumpa Lahiri, Juan Rulfo, Max Porter, Nathan Jurgenson, Sebastian Faulks.