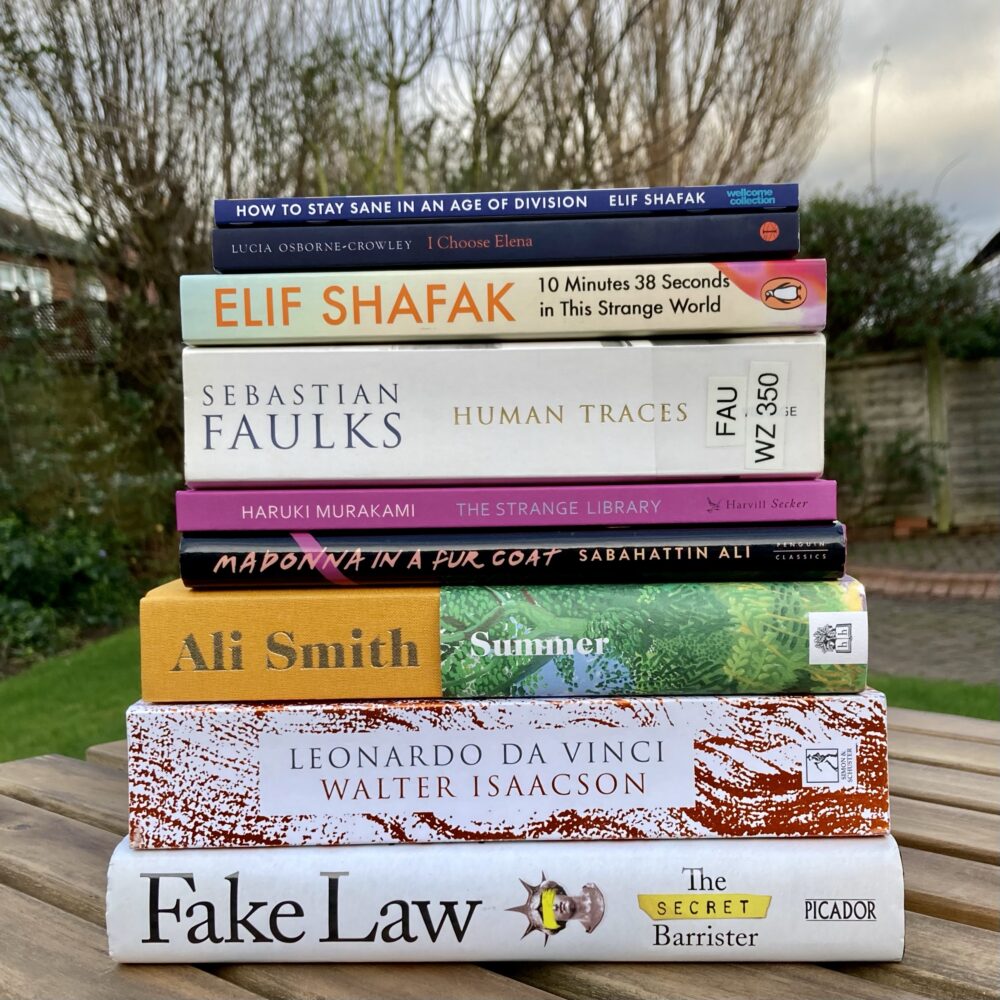

My favourite books of 2020

According to Goodreads, I’ve read 101 books this year, which is three fewer than in 2019. I’ve given ten of those books “five stars” on Goodreads, which seems a reasonable standard by which to deem that they were my favourite of the year.

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson

There are lots of biographies of Leonardo da Vinci; this one, Walter Isaacson’s 2017 book based primarily around Leonardo’s notebooks, is the only one I’ve read.

It was fantastic. Isaacson brought Leonardo to life as a complete, fascinating person. I had little idea how many different disciplines Leonardo held an interest in—I had no real idea of his contributions to the study of anatomy, maths, or engineering. I knew nothing of his personal life. I had no idea that he was so reluctant to finish any project he was given. And yet, by the end of Isaacson’s book, I felt like I knew Leonardo.

There were so many bits of this book which will stick in mind for a long time (including the tongue of the woodpecker!) but I was perhaps most amazed by the description of Leonardo’s work on the mechanism of closure of the aortic valve. Leonardo has this figured out in 1510, but it wasn’t until 1960—the same decade as the first heart transplants—that cardiology rejected the traditional understanding that Leonardo had disproved 450 years earlier.

I also enjoyed Isaacson’s occasional commentary on the complexity of writing a biography, and appreciated his clarity on occasions where his own views of circumstances were different to those of other notable biographers of Leonardo.

This was an absorbing and clear biography of a fascinating man and a true genius.

❦

“Above all, Leonardo’s relentless curiosity and experimentation should remind us of the importance of instilling, in both ourselves and our children, not just received knowledge but a willingness to question it—to be imaginative and, like talented misfits and rebels in any era, to think different.”

❦

“There have been, of course, many other insatiable polymaths, and even the Renaissance produced other Renaissance Men. But none painted the Mona Lisa, much less did so at the same time as producing unsurpassed anatomy drawings based on multiple dissections, coming up with schemes to divert rivers, explaining the reflection of light from the earth to the moon, opening the still-beating heart of a butchered pig to show how ventricles work, designing musical instruments, choreographing pageants, using fossils to dispute the biblical account of the deluge, and then drawing the deluge. Leonardo was a genius, but more: he was the epitome of the universal mind, one who sought to understand all of creation, including how we fit into it.”

❦

“The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril. In addition to digging out grubs from a tree, the long tongue protects the woodpecker’s brain. When the bird smashes its beak repeatedly into tree bark, the force exerted on its head is ten times what would kill a human. But its bizarre tongue and supporting structure act as a cushion, shielding the brain from shock.

“There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. It is information that has no real utility for your life, just as it had none for Leonardo. But I thought maybe, after reading this book, that you, like Leonardo, who one day put ‘Describe the tongue of the woodpecker’ on one of his eclectic and oddly inspiring to-do lists, would want to know. Just out of curiosity.”

“Pure curiosity.”

Summer by Ali Smith

Having now completed the seasonal quartet, I can confirm without hesitation that it is my favourite series of novels. And far from going out with a whimper, Summer was extraordinary.

If one was setting out to publish a novel a year reflecting the times in which we live, one could hardly have picked a better four years to work with than the last four. Smith’s ability to capture and reflect on the age of Brexit, coronavirus and George Floyd with such a publication schedule, while the rest of us are struggling just to keep up with events, is pure genius. This volume revisits some of the characters from the earlier novels, and I slightly worried that I’d struggle to recall them, given the time that has passed since I read the first of the novels—but they all came flooding back.

I feel a bit lost knowing that this series is now complete – it has been the series that I’ve most enjoyed and most anticipated in recent years. I’ll miss it.

❦

“Everybody said: so?

“As in so what? As in shoulder shrug, or what do you expect me to do about it? or I so don’t really give a fuck, or actually I approve of it, it’s fine by me.

“Okay, not everybody said it. I’m speaking colloquially, like in that phrase everybody’s doing it. What I mean is, it was a clear marker, just then, of that particular time; a kind of litmus, this dismissive note. It got fashionable around then to act like you didn’t care. It got fashionable, too, to insist the people who did care, or said they cared, were either hopeless losers or were just showing off.

“It’s like a lifetime ago.

“But it isn’t – it’s literally only a few months since a time when people who’d lived in this country all their lives or most of their lives started to get arrested and threatened with deportation or deported: so?

“And when a government shut down its own parliament because it couldn’t get the result it wanted: so?

“When so many people voted people into power who looked them straight in the eye and lied to them: so?

“When a continent burned and another melted: so?

“When people in power across the world started picking off groups of people by religion, ethnicity, sexuality, intellectual or political dissent: so?

“But no. True. Not everybody said it.

“Not by a country mile.

“Millions of people didn’t say it.

“Millions and millions, all across the country and all across the world, saw the lying, and the mistreatments of people and the planet, and were vocal about it, on marches, in protests, by writing, by voting, by talking, by activism, on the radio, on TV, via social media, tweet after tweet, page after page.

“To which the people who knew the power of saying so? said, on the radio, on TV, via social media, tweet after tweet, page after page: so?

“I mean, I could spend my whole life listing things about, and talking about, and demonstrating with sources and graphs and examples and statistics, what history’s made it clear happens when we’re indifferent, and what the consequences are of the political cultivation of indifference, which whoever wants to disavow will dismiss in an instant with their own punchy little

“so?

“So.”

❦

“Then she’d told Iris—foolishly, her selfish self knows now—about Art and herself going to visit the detainees in the SA4A Immigration Removal Centre and how a clever and thoughtful young virologist being held indefinitely there had taken pains to explain to them, and this was back in early February when nobody much was taking the virus seriously in England, about the dangerous-sounding virus that was beginning to take hold in various countries and had reached England via the airport right next to the Immigration Removal Centre they were sitting in now, from which the planes that took off over their heads made the room they were sitting in literally shake every few minutes, and the virus was apparently now also present in the city just down the road from here where they were about to go and stay for the night.

“He told them that if the virus happened to get into this centre he was being held in then all the detainees would catch it because the windows are made of a combination of perspex and metal bars, none of them openable to the outside world, the only air in there the recycled old air filtering through the place’s ventilation system.”

❦

“We’re always looking for the full open leaf, the open warmth, the promise that we’ll one day soon surely be able to lie back and have summer done to us; one day soon we’ll be treated well by the world.”

Human Traces by Sebastian Faulks

Goodreads tells me that, on page count, this 2005 novel is the longest book I’ve read this year. It’s also the longest I’ve ever had a library book: nearing twelve months now, as the library from which I borrowed it hasn’t been accepting returns since the start of Lockdown I. The current due date is June 2021.

I borrowed this as it was recommended by my friend and esteemed work colleague Julie, and I loved it. It follows the lives of two doctors in nineteenth century Austria, from their childhoods through their careers as specialists in psychiatry to their old age. They set up a clinic together despite developing contrasting theories as to the causes of and treatments for mental illness, and their intellectual differences both bind them together and drive them apart.

Faulks skilfully weaves together fictional biography with medicine, psychiatry, travel, the thrill of early scientific discovery, moral complexity, interpersonal relationships, love and philosophy – all things I really enjoy reading about. The sometime lengthy exposition of early psychiatric theory in the book is often singled out as a point for criticism, but I found it fascinating. I was completely absorbed into the world Faulks created.

It may have run to 786 pages but it felt far shorter. I’m thrilled to hear that a not-quite-a-sequel is coming in 2021.

❦

“‘So the Bible is not so sad in the end?’

“‘Yes, it is the saddest book in the world. We are asked to believe that God has played an infantile trick on us: he has made himself unobservable, as an eternal test of “faith”. What I read, though, is the story of a species cursed by gifts and delusions that it cannot understand. I read of exile, abandonment and the terrible grief of beings who have lost something real—not of a people being put to a childish test, but of those who have lost their guide and parent, friend and only governing instructor and are left to wander in the silent darkness for all eternity. Imagine. And that is why all religion is about absence. Because once, the gods were there. And that is why all poetry and music strike us with this awful longing for what once was ours – because it begins in regions of the brain where once the gods made themselves heard.’”

❦

“Happiness creeps up on you, does it not? You never see it arrive, but one day you hesitate and you are aware that there is something… additional.”

❦

“Psychosis, ladies and gentlemen, is the price we pay for being what we are. And how unfair, how bitterly unfair it is that the price is not shared around but paid by one man in a hundred for the other ninety-nine.”

I Choose Elena by Lucia Osborne-Crowley

Lucia Osborne-Crowley’s 2019 essay on the lasting effect of trauma in her life, exploring the effect that a rape at knifepoint when she was fifteen years old changed her life.

This is a deeply personal account which I found to be very powerful. Osborne-Crowley reflects on the influence literature had on her recovery, including Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels which the title references.

She also reflects on why her experience had such a profound impact on her life, in a section that knocked me sideways. This will stay with me.

❦

“I have spent ten years wishing I could disappear. I have tried every imaginable way to appraise my life, to outrun myself, to make a sacrifice out myself, always searching for the most profound and permanent act of disappearance. But I cannot, and I will not. Because to be invisible is to give up the only tangible thing I have to offer: this cautionary tale.”

❦

“I intend to survive. It is this line that made me realise the true significance of the term ‘survivors’. It does not refer only to surviving the traumatic incident itself, but the everyday terror that follows. The days and weeks and years of indignity that follow. Some days I think that part came closer to killing me than the man with a knife did. But I intend to survive.”

How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division by Elif Shafak

The Turkish writer Elif Shafak is the only one to appear twice in this list, a fact made more surprising by the fact that one book is fiction and one non-fiction.

This fairly short essay is a passionate and beautifully written plea for pluralism, understanding, thoughtfulness, empathy and kindness. Shafak draws on her personal experiences as well as contemporary events, from covid-19 to the death of George Floyd. Shafak reminds us of the dangers of polarisation and echo chambers and the important of dialogue and understanding.

My enjoyment of this book was, in part, one of those serendipitous times when you pick up the perfect book for the moment. Coming at a time when all of the above seem in short supply in the world, I found myself getting a little emotional reading this.

❦

“The moment we stop listening to diverse opinions is also when we stop learning. Because the truth is we don’t learn much from sameness and monotony. We usually learn from differences.”

❦

“Sometimes, where you genetically or ethnically seem to fit in most is where you least belong. Sometimes you are at your loneliest among people who physically resemble you and seem to speak the same language. There are many citizens across the world today – and their number is growing – who have a hard time recognising their countries, walking like strangers in their own homelands.”

❦

“Do not be afraid of complexity. Be afraid of people who promise an easy shortcut to simplicity. Nor should you be afraid of emotions. Whether it is angst or anger or hurt or sadness or loneliness. As human beings—regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, geography—we are emotional creatures, even those of us who like to pretend not to be, especially them. Analyse, understand and reflect upon where negative emotions come from, embrace them candidly, but also notice if and when they become repetitive, restrictive, ritualistic and destructive.”

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World by Elif Shafak

This is Shafak’s Booker-shortlisted 2019 bestseller. I picked it up on a whim when I saw it in a bookshop and vaguely thought I’d heard good things about it. It turned out to be an extraordinary book.

The book comprises three parts. Part One follows Tequila Leila’s lifetime of reminisces over the few minutes following her death, covering everything from her own birth into a polygamous family to her murder as a sex worker. Each memory focuses on a specific friend and the life of each of them is also explored. Part Two follows these close friends in the day following Leila’s murder. And the brief Part Three follows her soul into the afterlife.

I found this emotionally exhausting. The characterisation and storytelling were so strong that I sometimes forgot this was fiction. Despite the tragedy and emotional weight of the story, it is leavened with moments of laugh-out-loud humour. It felt to me like this book was as much about Istanbul as it was about the human characters. Definitely a favourite.

❦

“The only professed atheist among Leila’s friends, Nalan saw the flesh—and not some abstract concept of the soul—as eternal. Molecules mixed with soil, providing nutrition for plants, those plants were then devoured by animals, and animals by humans, and so, contrary to the assumptions of the majority, the human body was immortal, on a never-ending journey through the cycles of nature. What more could one possibly want from the hereafter?”

❦

“Nalan thought that one of the endless tragedies of human history was that pessimists were better at surviving than optimists, which meant that, logically speaking, humanity carried the genes of people who did not believe in humanity.”

❦

“Until the year 1990, Article 438 of the Turkish Penal Code was used to reduce the sentence given to rapists by one-third if they could prove that their victim was a prostitute. Legislators defended the article with the argument that ‘a prostitute’s mental or physical health could not be negatively affected by rape’. In 1990, in the face of an increasing number of attacks against sex workers, passionate protests were held in different parts of the country. Owing to this strong reaction from civil society, Article 438 was repealed. But there have been few, if any, legal amendments in the country since then towards gender equality, or specifically towards improving the conditions of sex workers.”

Madonna in a Fur Coat by Sabahattin Ali

This is the book on this list that I read most recently. It’s also the third on the list by a Turkish author, which I would never have guessed this time last year!

This is the 1943 Turkish classic by Sabahattin Ali, which has had a huge revival in Turkey, becoming the bestselling book for several consecutive years. I read the Penguin Classics 2016 translation by Maureen Freely and Alexander Dawe in a day (it was only 168 pages) and loved it.

The 1920s plot concerns a young Turkish man moving to Berlin to learn about the perfumed soap trade. He develops an intense longing for a woman he initially saw in a painting, and a powerful and moving—if somewhat unconventional—relationship develops.

This is a book about social changes in the first part of the twentieth century, and particularly morphing gender roles, but it is also full of profound longing. It oozes atmosphere.

Despite the small page count, Ali somehow manages to create complete characters who will live long in the mind, and to completely immerse the reader in a time and place, and to make larger observations about social change. It was great.

❦

“The essence of life is in solitude – wouldn’t you agree? All unions are built on falsehood. People can only get to know each other up to a point.”

❦

“Love is nothing like the simple compassion you describe, and neither is it a passion that comes and goes. It is something altogether different, something that defies analysis. And we are never to know where it comes from, or where it goes on the day it disappears. Whereas friendship is constant and built on understanding. We can see where it started and know why it falls apart. But love gives no reasons.”

❦

“For our lives were governed by trivial details. Indeed, trivial details were what true life was made of.”

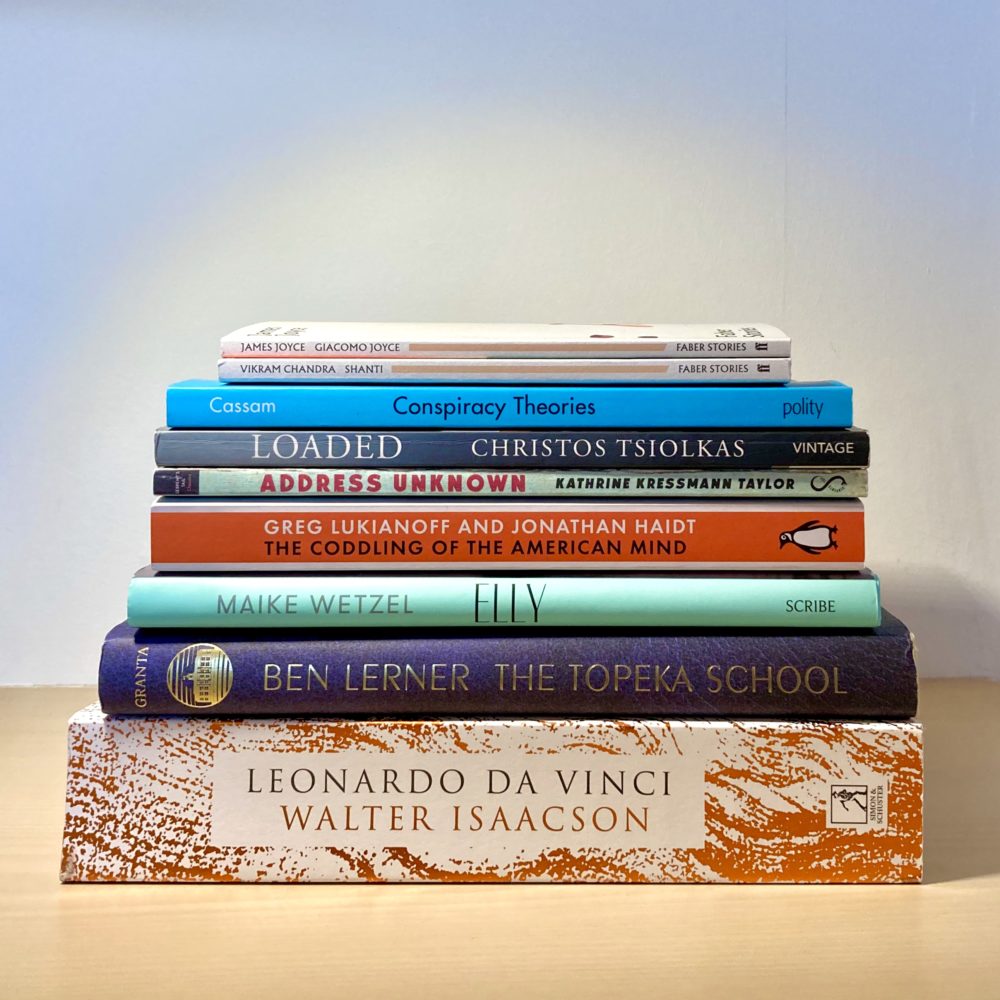

Marcovaldo by Italo Calvino

This isn’t in the photo at the top for the simple reason that I’ve returned it to the library! Like the rest of us, libraries have not had an easy time of 2020; I look forward to the day when we’re all able to browse them once again.

I loved Marcovaldo. First published in 1963, it is a collection of twenty short stories about a poor man who is fond of nature and rural life but lives with his family in a big Italian city. The stories follow a seasonal cycle, so that there a five set in each of spring, summer, autumn and winter.

In each story, Marcovaldo engages with nature or the physical world in some way, and the outcomes are always unexpected. There is a lot of humour in here (I could imagine Marcovaldo being reduced to a comedy character on TV), but there’s an equal amount of philosophy and some melancholy.

The writing was wonderful, simple and yet poetic. I enjoyed this so much that I didn’t want it to end, and tried to give myself time to reflect on each story before reading the next.

❦

“Once you begin rejecting your present state, there is no knowing where you can arrive.”

❦

“He would go out to take a walk downtown, in the morning. The streets opened before him, broad and endless, drained of cars and deserted; the façades of the buildings, a gray fence of lowered iron shutters and the countless slats of the blinds, were sealed, like ramparts. For the whole year Marcovaldo had dreamed of being able to use the streets as streets, that is, walking in the middle of them: now he could do it, and he could also cross on the red light, and jay-walk, and stop in the center of squares. But he realized that the pleasure didn’t come so much from doing these unaccustomed things as from seeing a whole different world: streets like the floors of valleys, or dry river-beds, houses like blocks of steep mountains, or the walls of a cliff.”

❦

“If your cart is empty and the others are full, you can only hold out so long: then you’re overwhelmed by envy, heartbreak, and you can’t stand it.”

The Strange Library by Haruki Murakami

This is one of four short books on this list. Given that a couple of years ago I would have said I didn’t like short stories, I would have been amazed to know that in 2020 I’d have four short books on my list of favourites, plus a collection of short stories in Marcovaldo.

First published in 1983, and translated into English by Ted Goossen in 2014, The Strange Library is a beguilingly strange short novel, perfect for reading in a single sitting. It’s a reflection of the book’s weirdness that there seems to be no popular agreement on whether this book is aimed at adults or children. It defies classification.

The plot concerns a young boy who visited his local City Library only to be kidnapped in the basement by an old man who wants to eat his brain. Had I known of that synopsis before I opened the book, I’d have passed on it: it sounds ridiculous and not at all like the sort of book I’d enjoy. And yet, Murakami’s writing combined with the beautiful production of the hardback lends the tale a hypnotic quality. It starts to feel like allegory—but for what?—while also being pure fantasy told in language which is entirely grounded in reality, but also somehow poetic.

This was a very short read, taking less than an hour, but was nevertheless memorable (and deserves a place on this list) for being unlike anything I’ve ever read before.

❦

“Why do I act like this, agreeing when I really disagree, letting people force me to do things I don’t want to do?”

❦

“‘Okay, kid. Then I’ll give it to you straight. The top of your head’ll be sawed off and all your brains’ll get slurped right up.’

“I was too shocked for words.

“‘You mean,’ I said, when I had recovered, ‘you mean that old man’s going to eat my brains?’

“‘Yep, I’m really sorry, but that’s the way it has to be,” the sheep man said, reluctantly.’”

❦

“At the same time, my anxiety had turned into an anxiety quite lacking in anxiousness. And any anxiety that is not especially anxious is, in the end, an anxiety hardly worth mentioning.”

Fake Law by The Secret Barrister

I enjoyed this so much that I ended up buying another copy for my dad.

One of the four books on this list to have been published this year, this is the second volume from the Secret Barrister. It concentrates on the gap between political discourse and the reality of legislation, and the gap between media coverage of court cases and the arguments and principles actually under consideration.

I am one of those strange individuals who occasionally downloads court judgements in high profile cases, particularly those that pertain to healthcare. I enjoy diving into the gritty detail and reveling in the clarity of expression in the writing of most judgements from higher courts.

This book was right up my street. Each chapter opens with the arguments concerning a case or piece of legislation as made out by Ministers or the media. The Secret Barrister then set out the legal reality of the situation, broadened the discussion with other exemplar cases, and rounded off with a summary of the fundamental principles underlying the relevant area of law.

The book was engaging and easy to read. The Secret Barrister was very witty and persuasive in their arguments. This book definitely earns its place rounding off this list.

❦

“At the heart of the concept of the rule of law is the idea that society is governed by law. Parliament exists primarily in order to make laws for society in this country. Democratic procedures exist primarily in order to ensure that the Parliament which makes those laws includes Members of Parliament who are chosen by the people of this country and are accountable to them. Courts exist in order to ensure that the laws made by Parliament, and the common law created by the courts themselves, are applied and enforced. That role includes ensuring that the executive branch of government carries out its functions in accordance with the law. In order for the courts to perform that role, people must in principle have unimpeded access to them. Without such access, laws are liable to become a dead letter, the work done by Parliament may be rendered nugatory, and the democratic election of Members of Parliament may become a meaningless charade. That is why the courts do not merely provide a public service like any other.”

❦

“Until it bites us, until we hear about our friend being abused by her co-workers for wearing a hijab, or see our ashen-faced husband come home, laid off without notice and with no idea where to turn, or learn that our teenage daughter is being paid below minimum wage and denied holiday pay by her leering, groping pub landlord, we can dismiss the true meaning of the protections we’ve spent decades constructing.”

❦

“If we are being misled, or misinformed, or even directly lied to, to what end is this being done? Whose interests are really being served?”

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Ali Smith, Elif Shafak, Haruki Murakami, Leonardo da Vinci, Lucia Osborne-Crowley, Sabahattin Ali, Sebastian Faulks, The Secret Barrister, Walter Isaacson.