‘Adolescence’ isn’t everything

There aren’t many areas of life where I agree with Kemi Badenoch—but, like her, I haven’t seen the Netflix series Adolescence. But I have seen, watched and listened to seemingly endless commentary about the dangers of boys being radicalised online by men with toxic views of masculinity… an issue which is hardly new, but which suddenly has a lot of cultural currency.

The tone has been broadly sympathetic: a chorus of concern, some hand-wringing, even a parliamentary debate. These boys, we’re told, are victims. Vulnerable. Impressionable. It could happen to anyone.

What’s striking is how rarely this is recognised as a familiar story.

Take the case of Shamima Begum. A British girl, groomed online as a teenager, who left the country at 15 to join ISIS. It’s the same story: a child radicalised online who goes on to take unwise actions. Yet her story is not seen as a cautionary tale, but as a scandal. Somehow, not a failure of safeguarding, but of loyalty. She wasn’t failed; she was treacherous. And so, she was stripped of citizenship and left stateless, as though none of this—her age, her vulnerability, the context—were relevant.

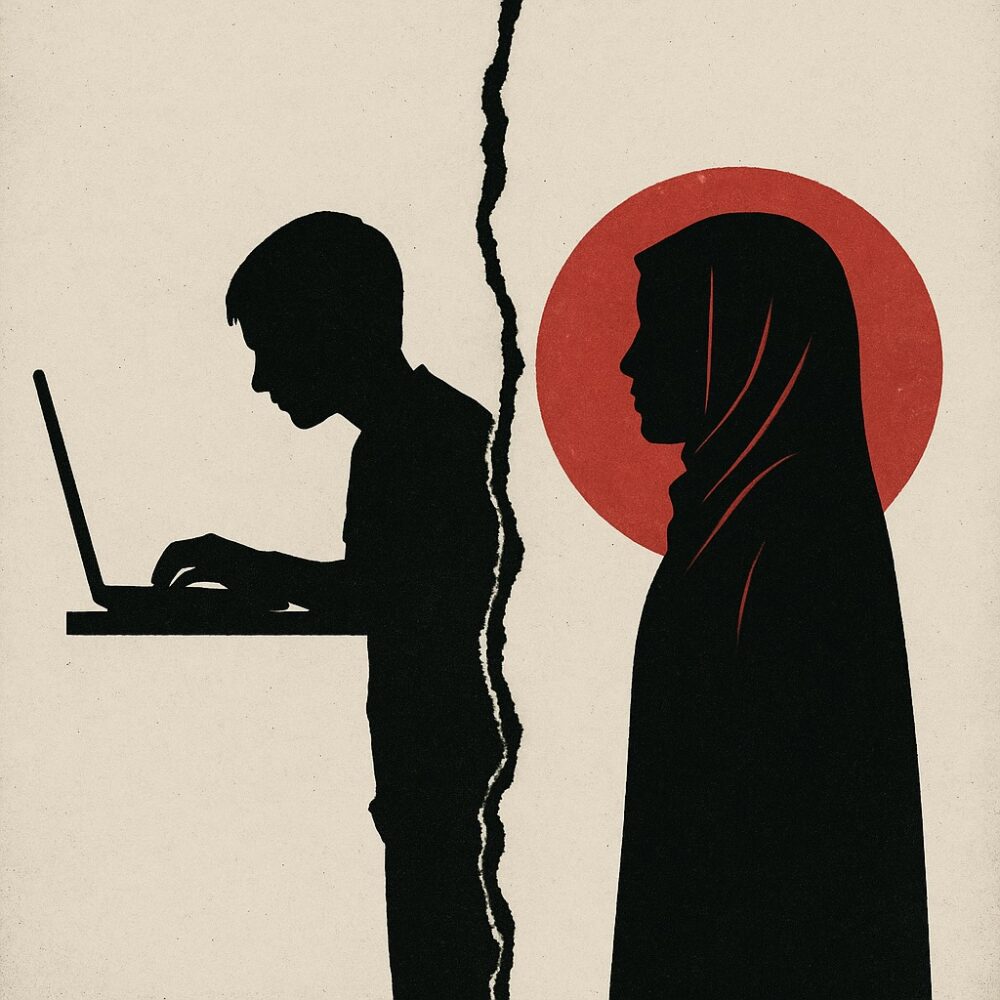

The contrast is hard to miss. When a fictional white boy is radicalised, it sparks a national conversation about prevention and empathy. When a real brown girl is radicalised, it becomes a question of punishment and blame. One is a victim; the other, a threat.

There is, of course, a racism to this. A gendered lens, too. But beyond that, there’s a practical cost to the inconsistency. Because when we fail to see the underlying similarities between different forms of radicalisation, we limit our ability to respond effectively to any of them.

The mechanisms—algorithmic echo chambers, the lure of certainty, the slow drip of ideology dressed up as empowerment—are the same for all forms of online radicalisation. It’s antivaxxers, it’s far-right conspiracists, it’s neighbourhood group chats convinced the local council has ‘gone woke’. It’s your parents claiming a local schoolchild identifies as a cat and is fed milk at school—it must be true, they saw it on Facebook.

The narratives may differ, but the structure is the same: beguiling lies which spread and manipulate people toward specific beliefs and actions.

Yet, our response too often focuses on the content rather than the common architecture. So much of the commentary around Adolescence has been focused myopically on online misogyny, and so many of the proposed solutions have been about building siloed strategies based on tackling that. We fail to see the core, underlying issues—not least because we insist on reducing some people to their ideology while elevating others above it.

In his particularly incisive podcast episode on Adolescence—the topic really is inescapable—Ryan Broderick suggests that the answer to all of this is love. If we’re really going to properly understand and tackle the problem of radicalisation, we need warmth, understanding and empathy, not just for certain groups of people who are affected by online radicalisation, but for all of them. If we can only muster empathy selectively—if we only see a radicalised child when they look like our own—we’ll never truly get to the root of the problem. We’ll just keep reacting to the symptoms that make the headlines, while the underlying conditions go untreated.

It’s not that the response to Adolescence is wrong. It’s that it reveals the limits of who we’re willing to care about. And when empathy is rationed, so is any real hope of solving the problem.

The image at the top was generated using GPT-4o.