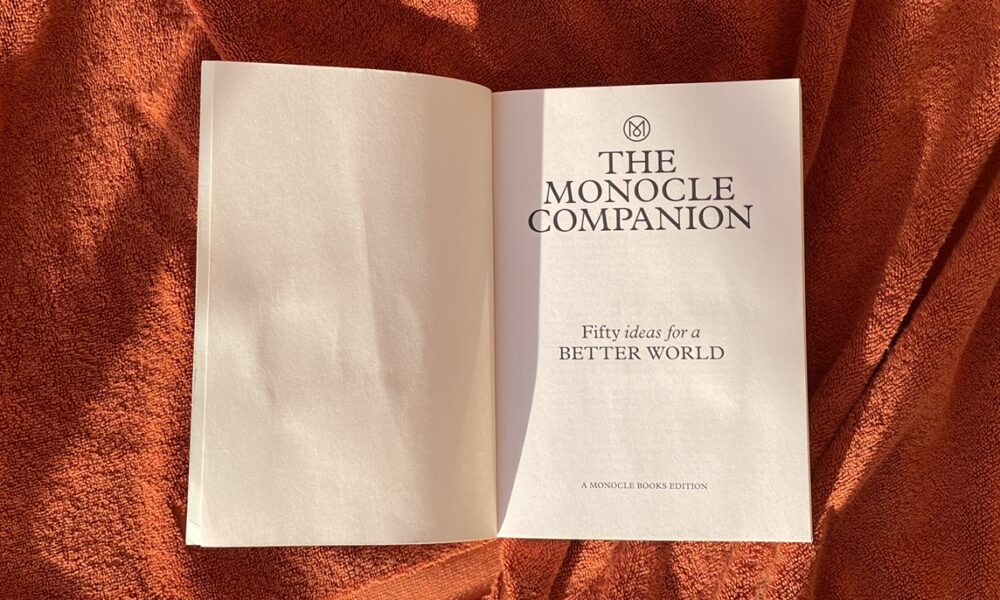

Yesterday, I promised to share some more from the latest Monocle Companion, so here are some thoughts on a grab-bag of essays.

An article on sleep by Claudia Jacob has some admirably straightforward advice:

So how can we simplify our sleep? The science tells us that the signs are abundant and free to see. Do you depend on an alarm to wake you? Do you need naps during the day and crave caffeine? Have you fallen asleep while hearing about a colleague’s weekend plans? If so, it’s probably time to get an early night to replenish your reserves. While the science of sleep is galloping ahead, you don’t need an app to understand it.

If only all journalistic health advice was so clear-minded.

In her essay on blame, Sally O’Sullivan says

Prince Harry’s memoir, Spare, sets up the mistaken idea that there is one right story, one truth. I’m sorry to say that this is never the case.

Every family member will see a situation differently and this multiplicity of truths is invariably complex. But no family is immune from these tussles. Indeed, the closer the relationship, the more likely it is that we will revert to blame.

This made me feel sorry for the Prince. I’ve seen so much vitriol directed at him for the phrase “my truth” often—wrongly, in my view—being taken to suggest that multiple truths are possible, rather than one singular truth. Here, he’s being criticised for exactly the opposite, based on exactly the same text.

The capacity of commentators to find fault may be infinite… this blogger included.

In an essay on reforming the modern approach to business, Josh Fehnert writes:

To conduct your business in good faith, in a way that’s transparent, rigorous and fairly managed, is a job in itself and everyone makes mistakes sometimes. Remember that it is OK to forgive people. That said, distant targets, such as decarbonising by 2050 or improving the gender balance of your board within a decade, ring hollow. Isn’t it better to get going right away, even if that means making a few missteps, and reach your goal rather than kicking the can down the road?

Bravo. I’ve been involved in too many tedious arguments about long-term plans for organisations, which everyone knows no-one will stick to. This sometimes boils down to confusing strategy with implementation. It’s good to have a long-term strategy which guides an organisation’s approach. It’s also essential to have a separate plan for implementation with a much shorter time horizon and tangible staging posts. The vicissitudes of life will necessitate changes in implementations, which the strategy ought to float above.

I recently read a ten-year strategy for an organisation which—for sound reasons—no-one reasonably expects to exist ten years hence. So, apart from hubris, what was the point in giving the strategy a decade?

In an essay on the recycling symbol, Richard Spencer Powell suggests adding

a visible green circle on the front of all recyclable packaging. That means no ifs, buts, or claims of being “partially recyclable”; it either is or isn’t.

Alternatively, if your plastic packaging isn’t recyclable (or doing so involves very specific efforts from the consumer) then brands should be obliged to put a red dot on it.

I appreciate the problem Powell is trying to solve: I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had to fish crisp packets out of recycling bins, a problem excavated by claims on the packaging that it is recyclable… but only via a specific scheme.

But it’s evidence that Powell underestimates the challenge: even within the UK alone, the items which are recyclable in local council bins vary enormously, as do the conditions in which the recycling must be presented. It’s clearly not feasible to have regional packaging dots.

But quite apart from that, the byline makes clear that Powell oversaw the design of this very edition of Monocle Companion. The book not only omits any recycling guidance, but also is perhaps the only one I’ve read this year containing no information on the sustainability of its paper source.

Perhaps he ought to start closer to home?

Albert Read writes:

I believe that imagination is something you can work at. If we’re attentive to ours, we can find all sorts of potential within ourselves. We should pay attention to our imaginative health in the same way that we look after our physical health and emotional wellbeing. All the studies show that being imaginative and creative makes us happier and more fulfilled. It’s the root of being alive.

I’m not keen on the ‘medicalisation’ of the topic, and I’m turned-off by the phrase ‘all the studies show’. But I completely concur with the wider point. Imagination and creativity are undervalued assets in life.

I’m not sure what made me relate this essay to work—I’m starting to see a bit of a theme in this post. Yet, I think that a little less adherence to change theory or management models in some health organisations, and a little more deep creative thought and engagement, would go a long way.

In a fantastic essay on friendship, David Sax says, in the context of the workplace:

Humans remain a social species and trust is the only currency that matters.

I reflected a lot on this. It’s obviously true: if I have a tricky professional decision to make, I run it past people I trust, not necessarily people with particular titles. Similarly, my close colleagues will often ask, ‘Who’s a sensible person to ask about X?’—which is really a question about whom I would trust.

I think I’m often critical of others for trying to use hierarchy in place of trust. But this made me reflect that perhaps I have become a bit slack in fostering trust too. It’s easy to get frustrated with being asked to explain principles repeatedly to different people, but perhaps I don’t spend enough time considering that it’s only the first time I’m explaining it to the latest person. Using it as an opportunity to patiently foster trust is probably a better approach than getting frustrated.

In an essay on commuting, Lilian Fawcett writes:

It’s a liminal time between commitments that gives our minds space to wander.

I know I’m not alone in finding solace in liminal spaces: sitting on a train, in an airport departure lounge, in a hotel lobby. I find it uniquely relaxing to be anywhere where I have a right and necessity to be, but where there is no expectation on me.

I also thoroughly enjoy my walks into work, but I hadn’t really connected these two preferences until I read Fawcett’s essay. Now I see that they are essentially the same thing… albeit walking is a little more active.