Choice and value

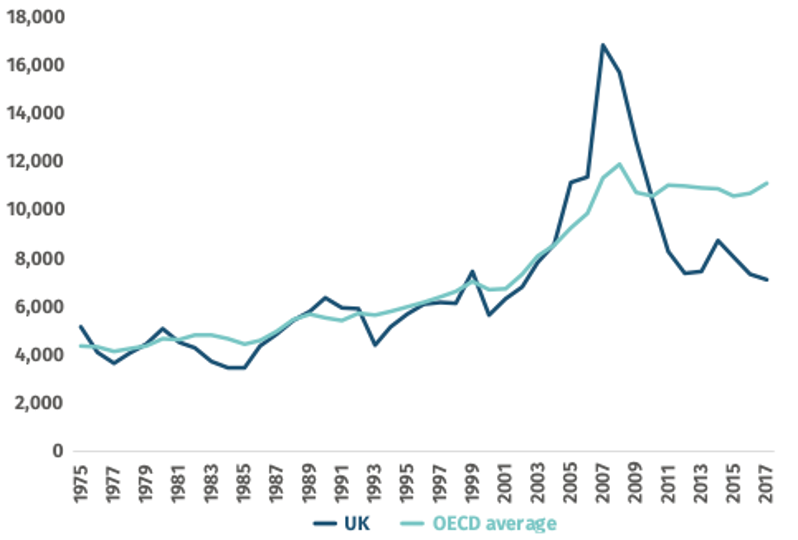

In 2008, about £1 in every £25 spent in a UK supermarket was spent in Lidl or Aldi. Today, it’s closer to £1 in every £5. These discounters have seen enormous growth, driven by a complex web of interacting underlying forces.

What is undeniable is that shoppers have traded choice for value. An average Lidl or Aldi branch carries 7,500 different products compared with 30,000 at your average Tesco or Sainsbury’s. Many people would rather pay less than have more product choice.

The big supermarkets, meanwhile, have tried all sorts of strategies to bridge the gap—attempting to offer full ranges while squeezing costs. It hasn’t really worked, hence their loss of market share.

You can’t have choice and value: they’re mutually exclusive, because choice begets inefficiency and waste.

Gordon Brown has a fascinating plan for the NHS: Increase patient choice, whilst simultaneously driving the cost of healthcare down to deliver better ‘value for money’. The plan is fascinating primarily because its two aims are utterly contradictory.

Yesterday, Wes Streeting told the BBC that he wants to:

make the NHS easier and more convenient to use, to give patients more choice, to get rid of the waste and inefficiency we see in the NHS.

It’s hard to grasp what’s hard to grasp. Choice requires oversupply, which is—by definition—inefficient.

I suspect what Streeting intends to do is allow patients to choose between location and speed, in an effort to spread demand. If you don’t mind travelling a little further, you might get seen quicker. There is a logical efficiency argument to that, and the process already exists in the NHS, but is perhaps under-promoted.

The problem is that it’s bad for the population’s health. Julian Tudor Hart proposed the Inverse Care Law decades ago, describing how the geographical areas of greatest medical need have the poorest supply of medical care. These populations also tend to be the least mobile, and therefore the least able to travel to shortcut the waiting lists.

Therefore, in the name of efficiency, one might well end up filling the available capacity with the most mobile and least needy patients. This might move the needle on the Government’s pledge to cut waiting lists, but it will exacerbate health inequalities.

What I haven’t quite figured out yet is whether this approach is intended to provide political cover for bolder moves to tackle inequalities, or whether this is the only game in town. Either seems plausible. I suppose we’ll have to wait and see.

This post was filed under: Health, News and Comment, Politics, Wes Streeting.