When people accuse politicians of lying, I generally roll my eyes. Almost a decade ago, I laid into my local MP for sending me an inaccurate letter. Guido Fawkes picked it up and called the poor guy a moronic liar. The episode was a whiny hurling of personal insults that achieved nothing of value. I still slightly regret it.

And these days, too often people choose to quote politicians out of context, wilfully misunderstand their position, or turn slips of the tongue into conspiracy theories. I have no interest in any of that.

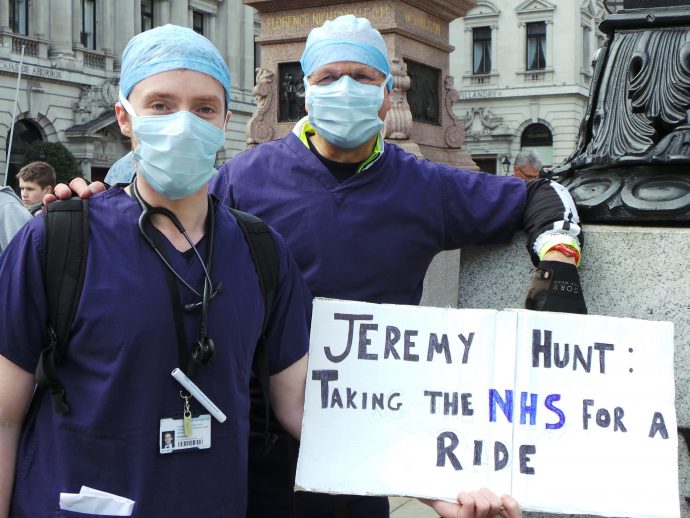

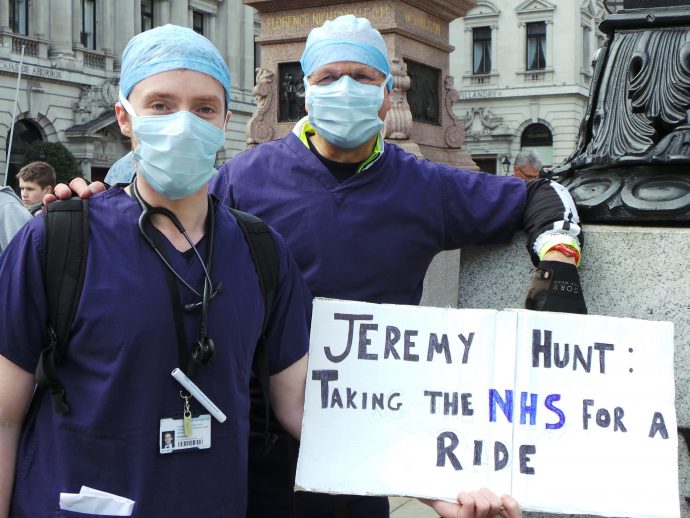

And yet. And yet. And yet, I have noticed a lot of inconsistency in Government statements on the Junior Doctors’ Contract dispute. I’m not accusing anyone of lying. I’m not even accusing anyone of being deliberately misleading. I’m just highlighting statements which, as far as I can see, don’t match one another.

Look through the list yourself. Check out the sources. Draw your own conclusions.

There will be no imposition.

Source: Government statement in response to petition, 21 March 2016

There has been no change whatsoever in the Government’s position since my statement to the House in February … We are imposing a new contract, and we are doing it with the greatest of regret.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 18 April 2016

Is it really the Government’s position that “no imposition” and “we are imposing a contract” mean the same thing?

No trainee working within contracted hours will have their pay cut.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 11 February 2016

No one will see a fall in their income if they are working the legal hours.

Source: Ben Gummer (Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Health), speaking in Commons debate, 21 March 2016

Is it the Government’s position that “contracted hours” and “legal hours” mean the same thing? Or did Gummer choose to to undersell the Government’s own guarantee on 21 March?

It will actually cost us more. If you’re going to ask more doctors to work at weekends, you’re going to have to pay more.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, on The Andrew Marr Show, 7 February 2016

[We have agreed] the cost neutrality of the contract

Source: Jeremy Hunt, in letter to Professor Dame Sue Bailey, 5 May 2016

Does the government consider “cost neutrality” and “it will actually cost us more” to have the same meaning?

What we do need to change are the excessive overtime rates that are paid at weekends. They give hospitals a disincentive to roster as many doctors as they need at weekends.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 13 October 2015

What we’re actually doing is giving more rewards to people who work the nights and the more frequent weekends.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, on The Andrew Marr Show, 7 February 2016

Was the Secretary of State mis-speaking when he said that the contract reduced excessive overtime rates at weekends, or when he said that the new contract increased them?

Certain features of the new contract will adversely impact on those who work part-time, and a greater proportion of women than men work part-time; women, but not men, take maternity leave and some aspects of the new contract have certain adverse impacts regarding maternity; certain features of the new contract will potentially adversely impact on those who have responsibilities as carers.

Source: Government Equity Analysis of new contract, published 31 March 2016

Shorter hours, fewer consecutive nights and fewer consecutive weekends make this a pro-women contract that will help people who are juggling important home and work responsibilities.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 18 April 2016

Is it the Government’s position that it got its own Equality Assessment wrong when it concluded that it discriminated against women?

No doctor will ever be rostered consecutive weekends.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 18 April 2016

Good practice guidance will be published in the near future to support employers, including guidance on rotas and scheduling, and will make clear that, where possible, routine rostering of consecutive weekends should be avoided.

Source: NHS Employers, 31 March 2016

Does the Government consider that “ever” and “where possible” mean the same thing?

We will make the NHS more convenient for you. We want England to be the first nation in the world to provide a truly 7 day NHS.

Source: Page 38 of the Conservative Party Manifesto, 2015

There is concern that the government may want to see all NHS services operating 7 days. Let me be clear: our plans are not about elective care.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 25 April 2016

Were the Conservatives up front about not including elective care in their plan to make the NHS more convenient with a truly 7 day service?

Source: First line of the first page of the Conservative Party Manifesto, 2015

The first line on the first page of this Government’s manifesto said that if elected we would deliver a seven-day NHS.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, speaking in Commons debate, 25 April 2016

Will Hunt correct the Parliamentary record for misquoting his own Party’s manifesto?

It is now not possible to change or delay the introduction of this contract.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, in letter to Dr Johann Malawana, 19 April 2016

We will pause introduction of the new contract for five days from Monday should the Junior Doctors’ Committee agree to return to talks.

Source: Jeremy Hunt, in letter to Professor Dame Sue Bailey, 5 May 2016

Is Hunt claiming to have achieved the impossible? Or was was his earlier statement erroneous?

Images used under by or by-sa licence as appropriate. Sources (in order of appearance): Ted Eytan, Roger Blackwell, University of Salford Press Office, Garry Knight, Ted Eytan (again), Garry Knight (again), NHS Confederation, Roger Blackwell (again). Thank you all!