Happy birthday, John Snow: you’ve never been so relevant

Today marks the 202nd birthday of John Snow, the anaesthetist whose work on cholera changed the course of modern medical history, kicked off the modern era of public health, and—in 2003—saw him voted the greatest doctor of all time in a UK poll.

Snow is best known for his work on the 1854 cholera outbreak in Soho, London. He used what we would now call epidemiological techniques to map the outbreak and figure out that cases were centred around the Broad Street water pump. It turned out that the pump was dug mere inches from a cesspit which was leaking into the water supply, causing illness in those who drank from it.

The relevance of Snow’s work to modern public health cannot be overstated. Having spent much of his bicentennial year writing speeches with the Chief Medical Officer, I’ve found myriad parallels to draw between modern public health and the 1854 outbreak, and today seems as good a day as any to share some of them.

❧

In the recent past, public health has been criticised for being too remote and too disconnected from the communities it serves, leading to a considerable gap between what public health teams provide and what people actually need. There are a number of ways of tackling this, but perhaps one of the most important developments in the last few decades has been the cultivation of truly integrated multidisciplinary public health teams. These bring together people with a wide variety of backgrounds and skills to work on some incredibly knotty problems.

And so it was with the 1854 cholera outbreak.

Snow couldn’t have worked on the outbreak alone, as he had no community connections. Without his partnership with Reverend Henry Whitehead, the curate of St Luke’s Church in Soho, Snow would never have been able to find details of the cholera cases he needed to draw up his impressive maps and tackle the outbreak. Only by working with someone with different skills and a different background was Snow really able to connect with his community.

❧

Following the Health and Social Care Act of 2012, much of the responsibility for public health services passed to Local Authorities. You don’t have to spend too much time around public health teams to hear occasional grumbles about this—while people recognise the potential for influencing the wider determinants of health by working in Local Authorities, there are often frustrations about having to convince non-specialists of the utility and evidence base of certain courses of public health action.

And so it was with the 1854 cholera outbreak.

People often believe that Snow himself removed the handle from the infamous Broad Street pump to prevent the spread of the cholera outbreak. He didn’t; probably because that would have been considered vandalism, and possibly because—as an anaesthetist—plumbing skills weren’t his forte.1 Instead, he talked his Local Authority into removing the pump handle. He initially found it difficult to get the message across, and his beautiful maps actually stem from his attempts to persuade the Local Authority to take action rather than from his investigation itself. Ultimately, the Local Authority either bought his argument or tired of him banging his drum, and removed the handle, saving the day.

❧

In modern public health, people often complain that national government interferes in the ability of local teams to act, either through interfering with the supply of funds, or through giving seemingly endless direction on things that should be considered or done at the local level.

And so it was with the 1854 cholera outbreak.

It’s an oft-forgotten footnote to the outbreak story that, having heard of what had happened in Soho, the national government ordered that the Broad Street pump handle be re-attached. There were too reasons for this: electorally, the closure of the Broad Street pump was a bad thing, for it was one of the most popular pumps in London, renowned for the clarity and taste of its water; scientifically, it was thought that the idea of faeco-oral transmission of disease was simply too disgusting to be true.

Yet when the pump handle was reattached, the outbreak didn’t restart. This was probably because the cesspit next to the pump well had been emptied—but it should also remind us that no matter how crazy they may seem, not all ideas from national government are completely mad.

❧

Effectiveness in modern public health can often involve challenging and overturning the status quo, sometimes in the face of considerable opposition from those with entrenched views.

And so it was with the 1854 cholera outbreak.

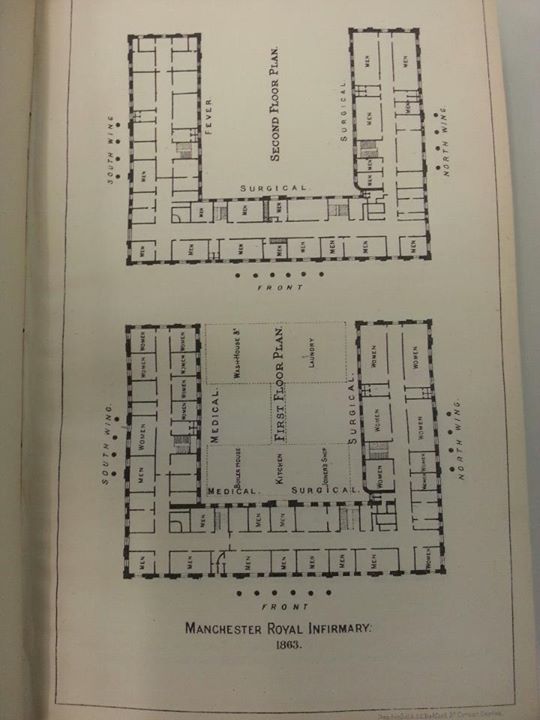

At the time of the outbreak, disease was thought to be transmitted by miasma—bad air. Today, it’s easy to underestimate the degree to which this faintly ridiculous theory was accepted: a glance through contemporary medical journals will reveal paper after paper on the design of hospitals and homes to promote the best flow of miasma. Indeed, one of the reasons so many Victorian hospitals had their morgues in the basement was so that miasma from the dead wouldn’t waft across other patients.

Snow—an anaesthetist, let us not forget—overturned the apple-cart of contemporary medicine by suggesting that disease could be water-borne. Virtually nobody believed him, and after 1854, he spent much of the following four years prior to his death trying to compile data to demonstrate his findings. His was a revolution that didn’t come easily. The Lancet, in an editorial on Snow’s theory in 1855, said

In riding his hobby very hard, he has fallen down through a gully-hole and has never since been able to get out again … Has he any facts to show in proof? No!

Yet, of course, germ theory proved Snow right—and The Lancet finally got round to publishing a correction on Snow’s 200th birthday.

❧

When working in public health in the North of England, it can often feel like breakthroughs made here are not fully appreciated, respected and integrated into practice until they’ve been endorsed by others—and particularly those in London.

And so it was with the 1854 cholera outbreak.

Snow was born in York trained at Newcastle Medical School. The first cholera outbreak he helped to tackle was in Newcastle in 1831, and though he was just 18 at the time, many believe that this is when he first developed the idea that cholera may be transmitted through water. Yet it wasn’t until his London-based work 23 years later that anyone took a blind bit of notice!

- Or maybe, like so many modern anaesthetists, he talked endlessly about the Hagen–Poiseuille law and considered himself something of a plumbing expert. ↩

The picture at the top of this post is of a bloke called Chris and the replica Broad Street pump in Soho. It was posted on Flickr by Matt Biddulph, and is used under its Creative Commons licence.

The other two pictures are my own.