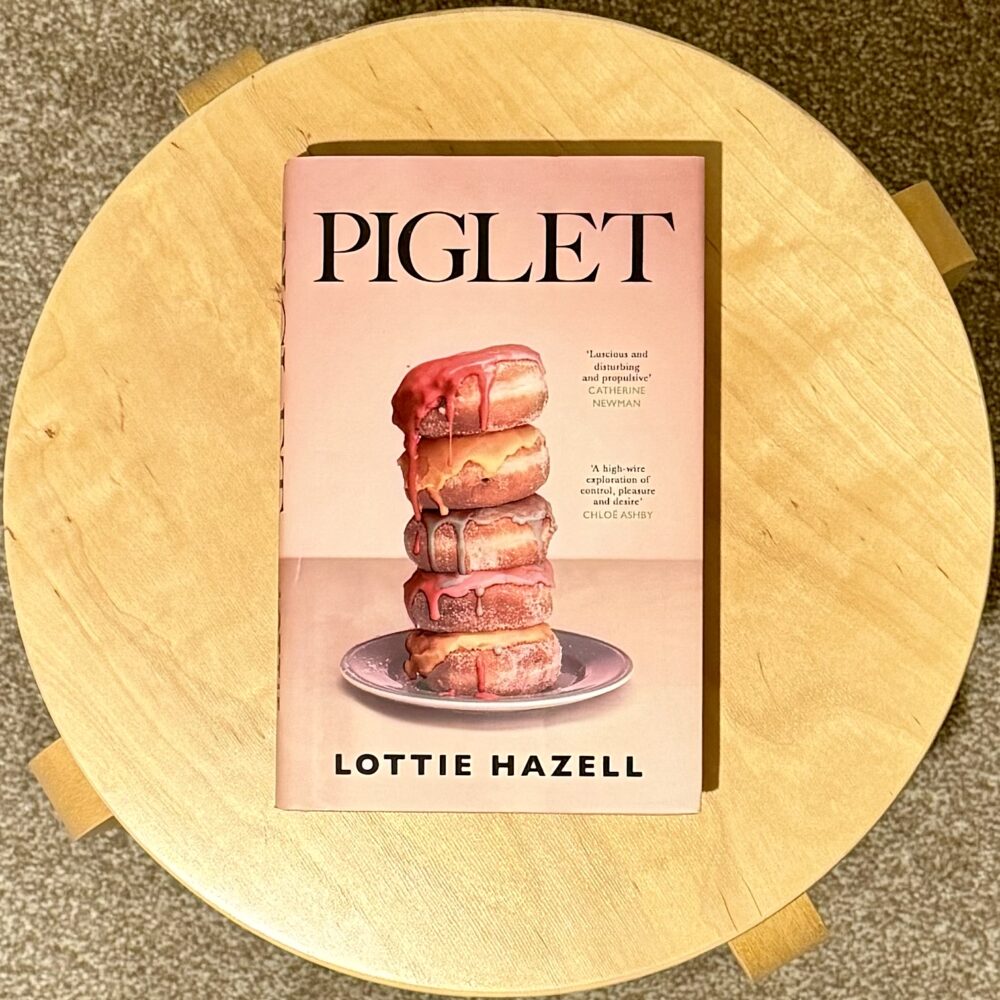

345 words posted by Simon on 16 October 2024

Sometimes in life, familial and societal expectations can feel constraining to the point of crushing, like an ever-tightening corset. Fighting against the restriction can lead us to rebel more than we otherwise would, in ways that might be harmful or increase the discomfort: over-eating to resist the pressure to fit into the corset, for example. And that’s the central metaphor of this book.

I’m a bit uncomfortable with that metaphor. Food in this book is all about indulgence, resistance is about self-control, and there’s an inextricable link between food and size. I think that’s a bit lacking in nuance—and this is a book full of close observation, ambiguity, and life’s grey areas. In essence, I think Hazell’s novel is better than its central idea.

The plot takes us from a few weeks before Piglet’s wedding to Kit, through the ceremony, and to the immediate aftermath. ‘Piglet’ is a family nickname, stemming from a childhood occasion on which she ate the lion’s share of her sister’s birthday cake—an event with more behind it than first appears (or than her parents realise). Piglet and Kit are in their early 30s.

Piglet works as an editor of cookbooks at a publishing house, which provides much interesting background and colour in the first half of the novel but oddly evaporates in the second.

Piglet is from a working-class household, Kit is from a wealthy family, and there are some closely observed class dynamics bubbling away as the wedding preparations continue. These didn’t always ring true—much like in the film Saltburn, it sometimes felt like a projection of what wealthy people imagine working-class people think of them, rather than something grounded in essential truth. The novel also felt like it too often pulled its punches, especially with a rather limp, polite ending.

Yet, all things considered, I enjoyed this. I was absorbed and entertained by it, and I liked many of Hazell’s turns of phrase and observations. It’s a flawed novel, but one that I nevertheless relished spending time with. I’ll certainly look out for Hazell’s next novel.