Sustaining the ego

The disreputable former former former Prime Minister of the UK was quoted in their least-favourite newspaper this week:

I thought it was the wrong thing to do, and a bit petulant. Plenty of other European leaders sustain referendum defeats and carry on with their duties.

Once I’d processed the lack of self-awareness inherent in the hypocrisy of a certain eight-letter adjective, I came to reflect on the oddness of the word ‘sustain’. Things that ‘sustain’ us support or uphold us; yet we ‘sustain’ injuries and insults. How can it mean such different things?

It turns out that the word is derived from Latin: ‘-tain’ comes from ‘tenere’, which, as even a passing knowledge of European languages will tell you, means ‘to hold’. The ‘sus-’ comes from ‘sub’, as in ‘under’. So, ‘to sustain’ is to hold something up, supporting it from underneath.

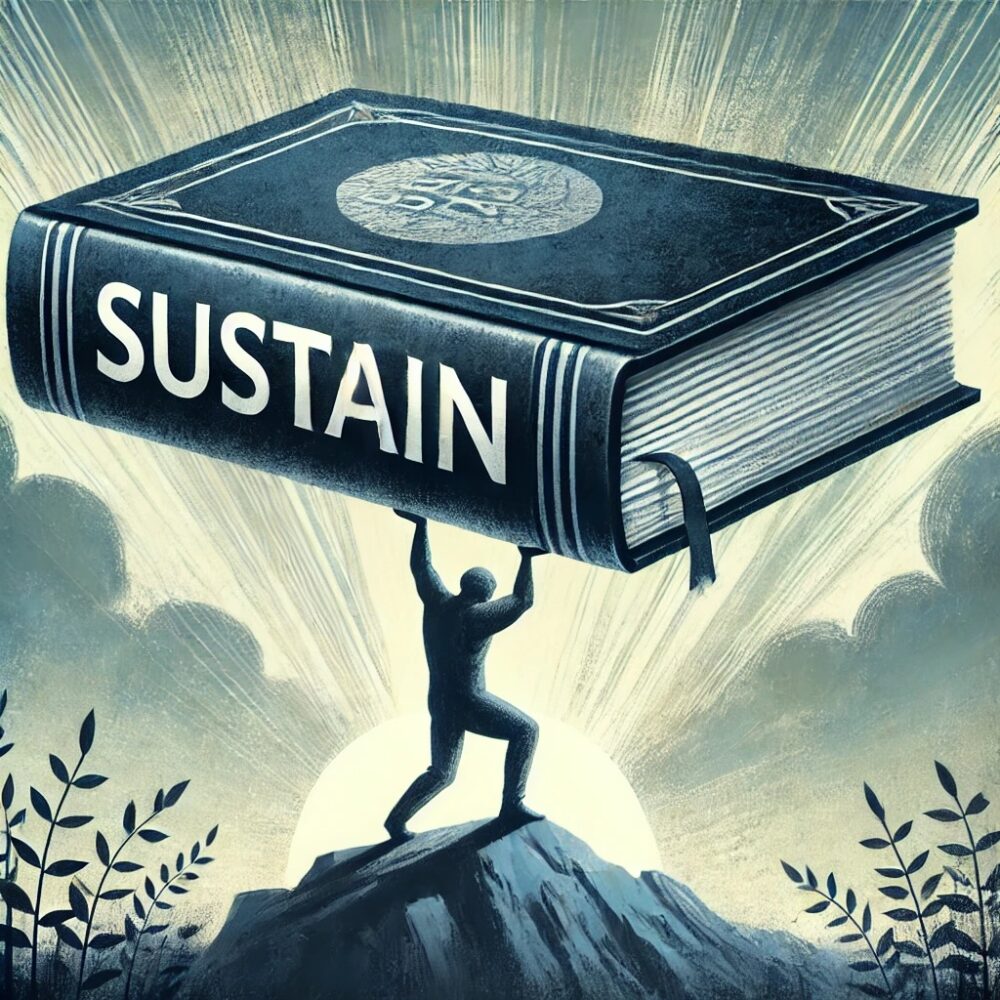

Immediately, the two senses reveal themselves: things can support us, or we can do the supporting. While the former is largely positive, the latter is more complicated. We can hold together a friendship, and find that sustaining it is a wholly positive experience. Or we can hold up a weight that’s threatening to crush us, with almost unbearable burden and discomfort. The rich tapestry of life means that sustaining something can sometimes be both fulfilling and impossibly difficult at the same time.

To give the pompous wally his due, in the context of the quotation, ‘sustain’ could be read in the plain sense of enduring the defeat, or as a jibe about supporting the defeat by being a bit rubbish.

‘To sustain’ contains multitudes. It’s nice to see the complexity and ambiguity of the human experience reflected in language sometimes.

The image at the top of this post was generated by DALL·E 3.

This post was filed under: Miscellaneous, Language.