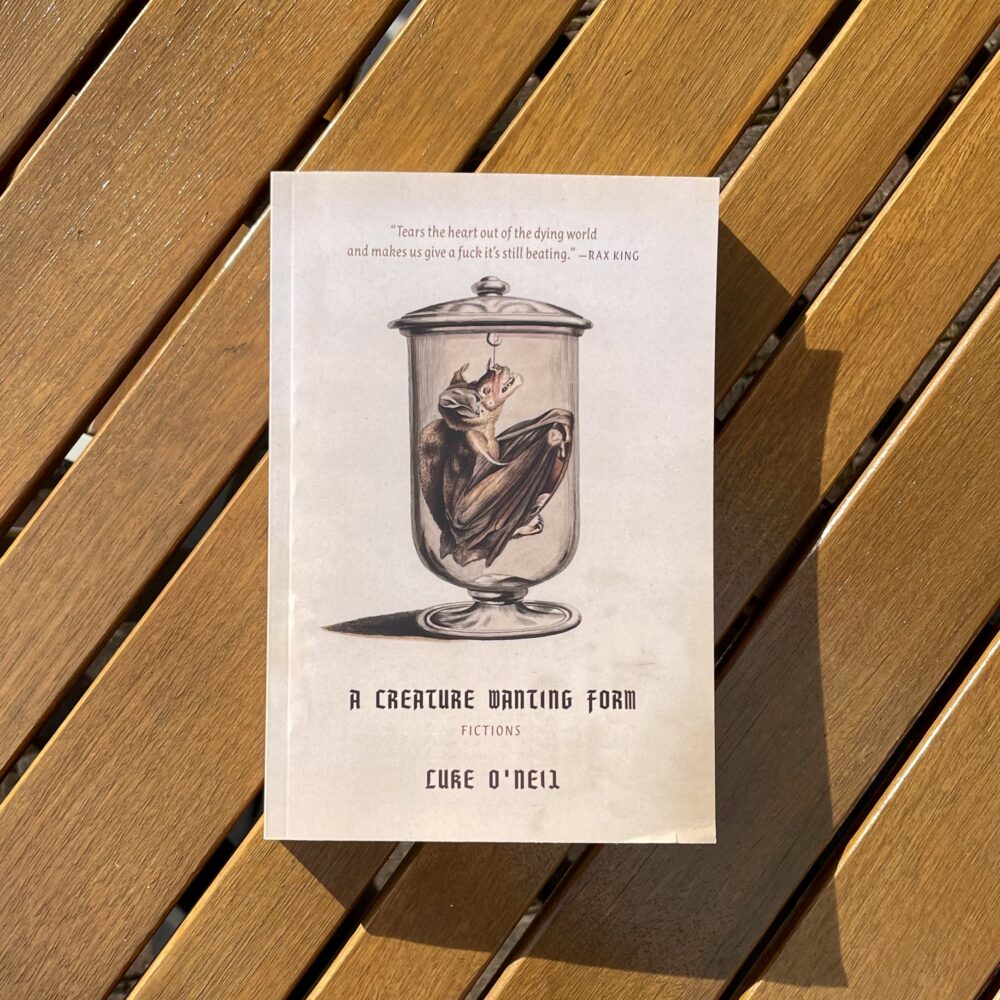

I know Luke O’Neil from his email newsletter Welcome to Hell World, where he has been heavily promoting this recently published book. It is the most unsettling book I’ve read in a long time. The book is a collection of short stories and poems which I think I’d broadly categorise as ‘horror’, but horror which is grounded in contemporary reality. This is a book about climate change, the breakdown of society, racism, police brutality, gun violence… essentially, all the catastrophes that stalk the Western world, and the USA in particular.

O’Neil writes in a distinctive style which eschews commas, and often other punctuation marks as well. I went backwards and forwards on how I felt about this: his style gives his text urgency and pressure, but it did become a little frustrating at times that everything had urgency and pressure.

The content, though, is both breathtakingly imaginative and yet also very much based in the contemporary real world. It is filled with myriad offbeat observations: O’Neils short section on the distance that the people killed by gun violence in the USA in a year would stretch if their bodies were laid end-to-end created imagery in my mind that I’ll never forget. Similarly, his climate change allegory about a pair of scuba divers accidentally abandoned at sea.

This book was quite unlike anything else I can ever remember reading, and I’d highly recommend it. Not every story within in resonated with me, and I found that the style of writing meant that I could only stand to read it in short chunks, but it will live long in my memory.

Some quotations… quite a few quotations… it’s very quotable…

Something is wrong with me but I think it’s probably the same thing that’s wrong with everyone so maybe it doesn’t matter.

The average adult in America is about 66 inches tall. Around 40,000 people die from gun violence here a year. 2,000 or so of them are children or teenagers so they won’t be that tall but we’re doing rough math here.

66 inches per body

x

40,000

=

2,640,000 inches

That’s roughly 42 miles of bodies a year.

Does that seem like a lot or a little to you because I guess I was thinking it would be more than that but then again I’ve never thought about it in these terms before so I have no frame of reference.

It would take you about an hour to drive from the beginning of the bodies to the end depending on traffic. Your kids would get bored and rambunctious on the trip in the back of the car and you’d have to turn around and be like alright you two that’s enough.

The average person would have a very hard time walking that far in one go. They’d have to make a lot of stops along the way and stay hydrated.

Imagine the biggest house on your block was always in flames and it burned all the time and it burned so often that you eventually just accepted as a given that there was going to be a house down the street that would be burning no matter what anyone did which was in any case not much. If firefighters were cops and when they came they just stood around and were like I don’t know what to tell you champ and got pissed off about you asking them to do anything at all then kicked your asshole in.

We have to address Fire House the stern mayor would say on TV and then they would get it under control for a while until they didn’t and the mayor would have to come on TV again. Goddamnit he’d say. This time I mean it.

You would get used to the smoke after a while right? It’s probably not going to get me you’d think then you’d go run your errands at the store and the mayor would get in trouble for fucking someone he wasn’t supposed to fuck and everyone would get preoccupied about that for a week or two.

We dragged the tree inside from the cold like it owed us money and set a bowl of water out for it so it could drink and pretend it was still alive for a little while longer pretend it had a future and then a few days passed and we still couldn’t find the goddamned box of lights in the wet basement so it stood there in the corner in its nakedness.

When the hornets were attacking me I dumped off my bike and ran back to my mother and she told me to take the jacket off. Take the jacket off she yelled at me but I couldn’t. I decided to roll around on the ground like I was on fire which I sort of was and thereby squishing all of the stingers into me. Stop drop and roll would have been one of the only things they taught kids about not dying at that point in history. Not getting into strange vans too I suppose. They didn’t even teach kids how to hide from gunmen yet when I was young that wasn’t invented yet.

I never used to understand in dystopian stories why people seemed to be racist against robots very early on in the narrative like before they had even switched to being evil but then I realized that in their fictional world they probably had some odious billionaire that everybody had long already hated for exploiting them by the time he invented the robots so then I got it. It’s humiliating enough just being ambiently enslaved by these guys I can only imagine what it feels like when the transaction becomes literal.

I read the comments under the video and some people said it was a shark but then other people said it was a dogfish and then other people still said a dogfish is actually a type of shark fucking dumbass why don’t you go kill yourself etc. You know how conversations go online.

Due to a miscount by the person leading the scuba expedition the couple emerge from the depths to realize the boat has left them behind. At first they presume that the mistake will be rectified in the way we all do when something goes wrong. Well this is fucked but certainly order will be restored presently we think.

She didn’t pay attention at first because she was busy cultivating her maladies.

A friend called that I haven’t spoken to since the early days of the pandemic back when you would call your friends or Facetime them and such and they’d go like what the fuck is going on ha ha ha and you’d go I don’t know ha ha ha back before millions of people died.

The Mall of Louisiana was trending and she thought oh here we go again and then she clicked on it and it turned out it was because a python was on the loose and she let out a sigh of relief because it was only a twelve-foot-long monster and not some guy. At least a monster will only attack when it’s hungry.

Every so often I’ll go in to see a new orthopedist or spine doctor and this thirty-two-year-old guy in his comfortable sneakers will go oh yeah I have a bad back too I know how you’re feeling bro and it’s like wait did I come to the wrong place? You literally work at the back store.

I don’t know maybe they want you to register their capacity for empathy or something but it always feels like eating at an emaciated chef’s restaurant.

This doctor today told me about his back but I wasn’t seeing him for that kind of pain it was on the other side. Front pain. No one calls it front pain. No one says I’ve got a bad front. I happen to have a bad front but no one says that.

The Bible was basically a Google doc where everyone had editing permission turned on.