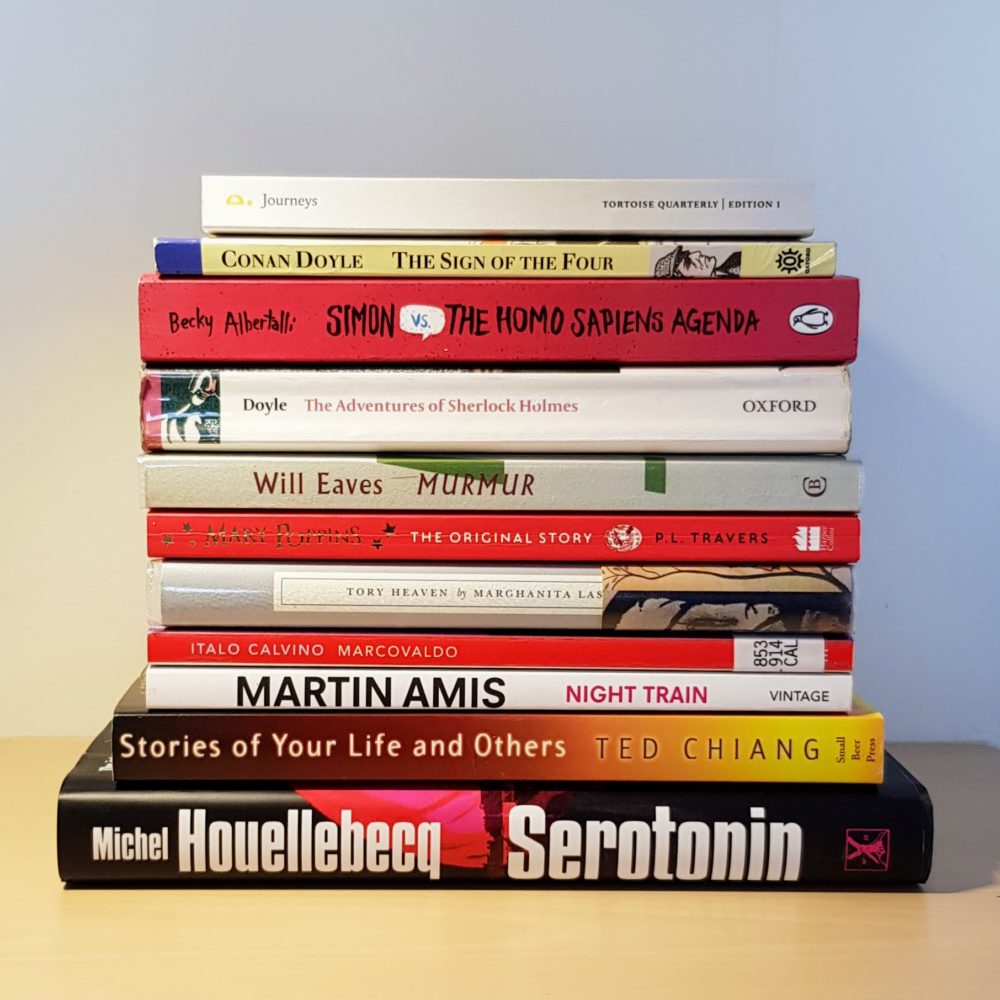

What I’ve been reading this month

I’ve eleven books to tell you about this month.

Marcovaldo by Italo Calvino

I loved this book. First published in 1963, this was a collection of twenty short stories about Marcovaldo, a poor Italian man who was fond of nature and rural life but lived with his family in a big city. The stories followed a seasonal cycle, so that there were five set in each of spring, summer, autumn and winter.

In each story, Marcovaldo engaged with nature or the physical world in some way, and the outcomes were always unexpected. There was a lot of humour (I could imagine Marcovaldo being reduced to a comedy character on TV), but there was an equal amount of philosophy and some melancholy.

The writing was wonderful, simple and yet poetic. But then I really like Calvino’s style, and know that it isn’t universally loved. The translation I read was by William Weaver.

I enjoyed this so much that I didn’t want it to end, and tried to give myself time to reflect on each story before reading the next.

Tory Heaven or Thunder on the Right by Marghanita Laski

This satire was first published in 1948, but if I didn’t know that, I’d have guessed that it was published last year. (In fact, it was republished by Persephone in 2018.)

The plot followed five people who, having been marooned on a desert island for some years, returned to England in 1945 to find it transformed into “the England of all decent Conservatives’ dreams.”

The country was divided along strict class lines, with every citizen receiving one of five Government-assigned grades, and required to live in accordance with what would be expected of their class. The novel primarily focused on the experiences of the privileged James Leigh-Smith (indistinguishable from Jacob Rees-Mogg), and largely left the reader to fill in the blanks and draw the moral lessons.

This was a really easy and fun read with a clearly enduring underlying message.

Mary Poppins by PL Travers

Wendy loves Mary Poppins, so after 16 years of not entirely voluntary viewings of the Julie Andrews film, the more recent Saving Mr Banks and Mary Poppins Returns, and countless features and documentaries, I decided it was time to engage with the original source material.

Obviously, it was a children’s book, but I was surprised how dark it was—and it was more interesting for it.

Mary Poppins, a truly memorable character, was acid-tongued, cold and vain. Mr and Mrs Banks had little interest in or interaction with their children.

I think many younger children would be scared by the situations into which Poppins lures the children, such as the full moon birthday party in which shes surrounded by snakes.

Neither the book nor the character have the redeeming and nurturing warmth I expected, which left me more intrigued than if this had been the more saccharine tale I imagined.

Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq

I had never read anything by Houellebecq before, but knew of his reputation for gloom. This book lived up to that reputation, mostly in a good way. I read the translation by Shaun Whiteside.

The protagonist was a depressed agricultural advisor to the French government on farming and agricultural matters. He was prescribed a novel antidepressant which increased his serotonin level (hence the title). The novel followed this not entirely likable character as he made increasingly strange life choices.

The high suicide rate among agricultural workers is well known, but this novel made me think a bit more about the myriad causes of this, especially in modern society. It was also good at giving a slightly different perspective on the experience of depression and medication. There was a good dose of dark humour mixed in with the tragedy.

There was a fair amount of gratuitous sex, including bestiality and paedophilia, which seemed like it was there more to shock than to perform any intrinsic function. Also, in one of those bizarre turns of fate, there’s a section in this reflecting on Arthur Conan Doyle’s short stories, which I was reading at the same time!

Night Train by Martin Amis

This was a book that started off as a crime procedural narrated by a policewoman called Mike, but turned out not to be a crime procedural at all. It was rather a sort of dark fictional philosophical exploration of suicide.

By pure coincidence, I had Miles Davis playing as I read much of this, and I was struck by how the writing seemed ‘jazzy’: police procedural cliche played with, improvised, turned on its head, and using the same forms to different ends. I enjoyed it.

The Sign of the Four by Arthur Conan Doyle

Contrary to most of the reviews I’ve flicked through, I enjoyed this less than A Study in Scarlet. It felt like there was more padding, and the long narrated resolution at the end felt more tedious than than the second part of the first book.

While I of course accept that the casual racism and pejorative language used by Conan Doyle reflect the social mores of the time it was written, the quantity of it in this volume became a bit wearing.

Simon vs the Homo Sapiens Agenda by Becky Albertalli

I picked this up because it was featured in an article about how brilliant ‘young adult’ fiction had become and how we should all be reading more of it. It was a ‘love through secret correspondence’ story with a gay 16-year-old high school student as the protagonist and narrator.

The straightforward plot dealt with issues of contemporary high school life, including traditional tropes like bullying and blackmail, and some more modern concerns, such as emails and blogging.

It felt tightly targeted at its audience: many of the cultural references passed me by somewhat (though I can’t be certain whether that was an age thing or a not-being-American thing). It is narrowly focused on high school life, and it limited itself to the sort of language teenagers use. There is a very teenage dichotomy in which almost everything in the book is either “freaking awesome” or terrible, which felt true to life, but a little wearing. Overall, the writing felt a bit teenage, which is what the author was going for, but doesn’t really have a great deal of interest for me.

All things considered, this seemed like a well-constructed book, but it didn’t really convince me that we should all be reading more young adult fiction.

Murmur by Will Eaves

This was a novel based on the imagined thoughts of Alan Turing as he experienced chemical castration and the associated psychological therapy.

In fact, the main character was a sort of ‘version’ of Turing called Alec Pryor, but having read a biography of Turing relatively recently, I recognised that many of the peripheral characters share the forenames of similar characters in Turing’s life. As if that wasn’t a complicated enough premise, several of the sections were dream sequences imagined by Pryor.

This layer upon layer of narrative complexity allowed Eaves to explore all sorts of interesting territory relevant to Turing’s life, from the morality of his treatment to the nature of consciousness to the development of artificial intelligence.

This was a very clever book which I think would reward multiple close readings. I often found myself a bit disorientated in terms of the plot, and while that sometimes made it a bit of a chore, I mostly found myself carried along by the writing, the fantastically poetic imagery, and the exploration of complex ideas.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle

A collection of twelve short stories about Sherlock Holmes cases narrated by Dr Watson. Obviously a classic and one where everyone knows what they’re getting!

I personally preferred getting engrossed in the full-length novels earlier in the series than these short stories, but I still enjoyed seeing how the characters developed over the course of the collection.

Journeys: Tortoise Quarterly, 1ed

Tortoise Quarterly is more magazine than book—it features thematic collections of longer articles from the Tortoise website.

In this edition, I particularly enjoyed Matthew D’Ancona’s account of experiencing delirium while he was a patient on a high dependency unit, Ian Ridley’s moving story of his wife’s death from cancer, and Tanyaradzwa Nyenwa’s reflections on working as a cold caller.

Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang

I fully recognise that this has a reputation as one of the greatest collections of short science fiction stories ever written, but it was just not for me.

I don’t usually enjoy science fiction but decided to challenge myself with this: it has a reputation for being so accomplished that it appeals to people who don’t usually enjoy science fiction. But I found it a real slog to get through.

I’m not sure what it is that generates such a negative reaction in me. I think it might be something to do with the fantastical nature of much science fiction—I don’t like fantasy stories either, so perhaps my imagination is limited to stuff grounded in reality.

I think it might also be something to do with the writing, which often struck me as inelegant, despite clearly being loved and respected by better informed people than me—to me it often felt more scientific than poetic, and I think I prefer poetic descriptions of emotions (not ‘Neil was consumed with grief after she died, a grief that was excruciating not only because of its intrinsic magnitude, but also because it renewed and emphasised the previous pains of his life.’)

So I’m still not a fan of science fiction.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Arthur Conan Doyle, Becky Albertalli, Italo Calvino, Marghanita Laski, Martin Amis, Mary Poppins, Michel Houellebecq, PL Travers, Shaun Whiteside, Sherlock Holmes, Ted Chiang, Tortoise, Will Eaves, William Weaver.