What I’ve been reading this month

I have just four books to tell you about this month.

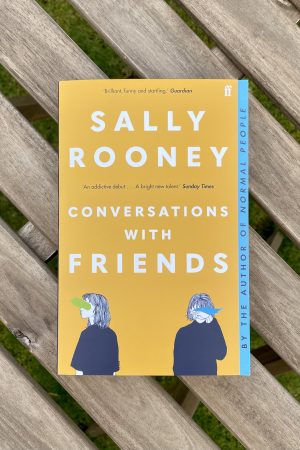

Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney

Rooney’s 2017 bestselling debut is one of those books that is so wildly popular and widely read that writing about it seems redundant. In fact, I thought I’d read this book some years ago, shortly after I read Normal People. But I think I was confused: I read Rooney’s short story Mr Salary a couple of months after that.

I didn’t especially enjoy Normal People, finding it a bit flat and claustrophobic, and I didn’t think much of Mr Salary either, finding the dialogue unconvincing. Yet, I enjoyed Conversations with Friends.

As you almost certainly already know, the plot concerns two University students (former lovers) who form a friendship with an older married couple, and the complex web of relationships which develops between the four of them.

For what it’s worth, I still think Rooney’s dialogue is astonishingly unrealistic given how widely praised it is: this is a novel where everyone talks in sentences and paragraphs, and can spontaneously express complex thoughts and feelings with immediate precision. But this book did have a lot going for it in terms of characterisation and emotional complexity.

All things considered, I enjoyed this book enough to seek out the newly published Beautiful World, Where Are You.

How to be Perfect by Michael Schur

This is a recently published “popular philosophy” book by the writer of the television comedy series The Good Place. I picked it up mostly because I enjoyed that series.

The book is a guided tour of some schools of thought on ethics and philosophy, along with (mostly humorous) examples of how these relate to everyday life. I found the discussion mostly superficial, which is really a result of the structure and the decision to cram so much into a short book.

The writing style was, for my liking, far too conversational in tone, to the point where I slightly struggled to understand parts and had to go back and mentally “read them aloud” to parse what Schur was trying to say. I found that annoying.

This just wasn’t up my street (which, as you’ll see, is a bit of a theme this month: poor choices abound).

All of that said, the last chapter—concerning apologies—was a cut above the rest. It’s quite disconnected from the rest of the book, and while I still found the writing style a bit painful, I think this chapter could be published and well-received as a separate essay.

The Kiss Quotient by Helen Hoang

This 2018 gender-swapped reworking of Pretty Woman is not my usual sort of novel, but I wanted something light and easy after a run of slightly dull books that I’d struggled through.

This fits that bill. While it was never going to be a book I’d love, I appreciated its straightforward plot and implausible but easy-to-follow dialogue. The characters were lightly sketched, as was appropriate for the plot. Unfortunately, I couldn’t help but repeatedly misread the main character’s name, Stella Lane, as Stena Line, which often made me laugh.

This novel has spawned a couple of sequels: this didn’t have enough of an effect on me to consider picking them up, but that’s no real criticism given that I knew it wasn’t my usual kind of novel when I bought it.

Broken People by Sam Lansky

Published in 2020, this Is Sam Lansky’s semi-autobiographical novel about coming to terms with our own past. The plot concerns a character—also called Sam—working with a shaman who offers ‘open-soul surgery’ which fixes ‘everything that it is wrong with you’ in three days.

I thought this was an interesting concept, but the book didn’t quite live up to it. I suppose I was hoping, in the end, for a discussion on how the process didn’t work, and how life and our own interaction with our past is altogether more complex than the conceit suggests. Unfortunately, Lansky delivers the opposite.

The ‘surgery’ consists of drug-fuelled trips into angsty memories, with superficial (and really quite dull) reflections on how they have shaped the present character, somehow leading to a positive and hopeful outcome. I didn’t find myself drawn into the process or the plot more broadly.

This just wasn’t really my cup of tea.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Helen Hoang, Michael Schur, Sally Rooney, Sam Lansky.