When I went to give blood earlier this week, a nurse asked me to confirm my date of birth. I did so, and she commented on how I shared my birthday with the late Queen. She wasn’t wrong, but it was a slightly peculiar moment.

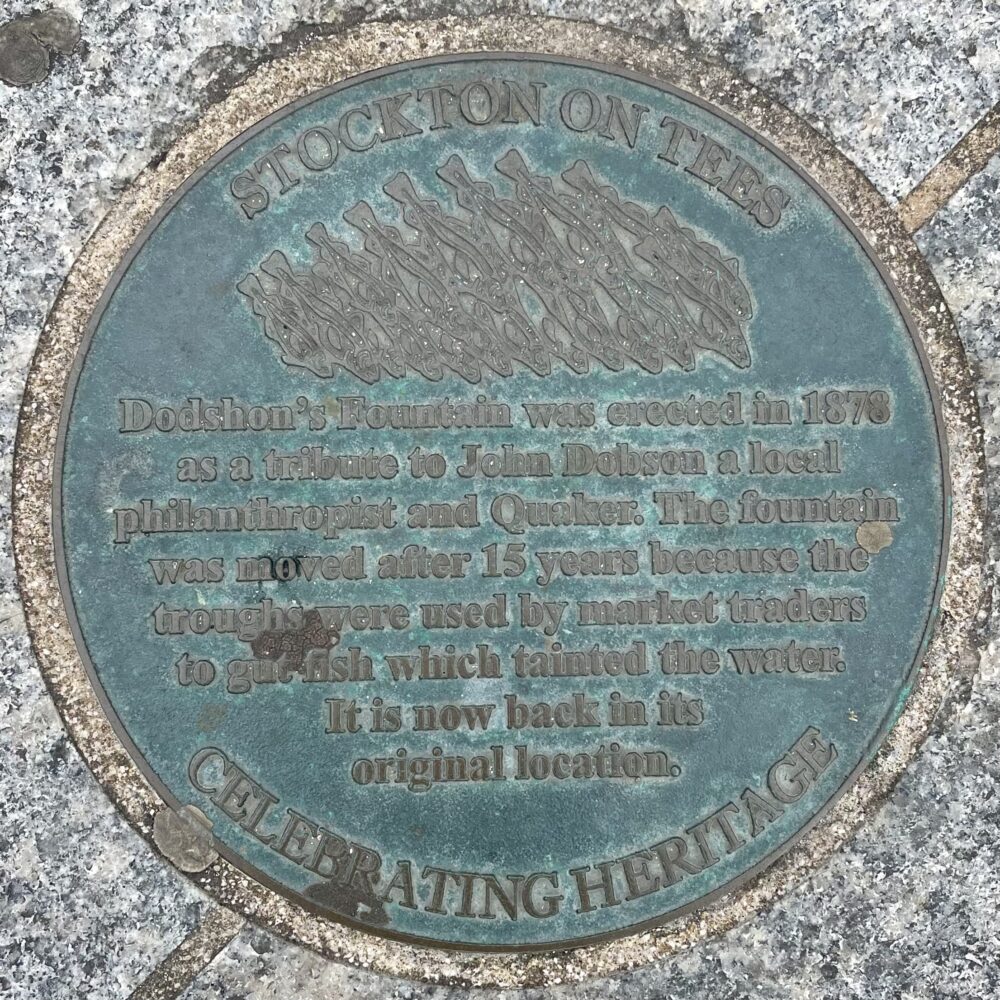

Wandering down Stockton High Street, I discovered via his memorial fountain that I also share a birthday with John Dodshon, a 19th-century Quaker philanthropist. And then I thought: surely I would have noticed such a prominent fountain with my birthday on it when I lived in Stockton?

And so I descended a watery rabbit hole.

Dodshon’s memorial drinking fountain was unveiled on Monday 26 August 1878. The Stockton Examiner described it as ‘a massive structure of stone’ with ‘a rather commanding appearance.’

But what did he do to deserve such a memorial? The newspaper considered it ‘unnecessary to say much here’, save that he ‘distinguished himself, and the many qualities of his nature fitted him for the different walks of life in which it was his delight to treat, and helped to make him a useful and esteemed townsman.’

But an anonymous letter to the Stockton Examiner a few weeks before the unveiling took a rather different, and rather more intemperate, view:

I have for some days been wondering what was about to be done in the middle of our much-boasted High-street, and now I learn that the site has been fixed upon to erect a memorial fountain in perpetuation of the memory of the late Mr John Dodshon. I confess I was astonished at this, and upon making inquiries I was informed it was a public monument! Really, what next, I wonder? Public monument! I pretend to know something about Stockton and what is going on, but I never heard of a public fountain to John Dodshon before.

What has Mr John Dodshon done for the town? Let’s know that first, and act when the question is answered. Verily, it seems our Town Council will allow Tom, Dick, and Harry, to erect monuments to their deceased chums if they only take it into their heads to do so. If those who are the prime movers in this scheme had only looked round, they might easily have found some more useful purpose for spending money—even to glorify the uneventful life of John Dodshon.

I have every respect and admiration for the late Mr Dodshon, but I cannot see that there is anything wise in sticking up a privately-provided fountain, the design of which has not been submitted to the public,m and of which everybody seems to be in ignorance about, in one of the finest streets of Great Britain. I hope the Town Council will reconsider this matter at their next meeting and come to some other conclusion upon it before the fountain is knocked down in disgust as a street obstruction.

‘Uneventful life’? ‘Street obstruction’? Blimey!

Clearly, there was something of a chorus of disapproval—so much, in fact, that it was mentioned in the local MP’s speech at the unveiling:

We regret to hear that some objections have been made to this monument occupying as it now does a portion of this magnificent High-street. No doubt it occupies a certain portion of space, and I am free to confess that I am one of those who hope that the time will come—and I must say I think it is not far distant—when all these hideous structures in our midst will be swept away, and this market place will be devoted to its more legitimate purpose—the accommodation of those who frequent our lively, rising, and increasing market.

When the time comes to which I have just referred, I am sure the Corporation will be as liberal as at present, and if we have to find a substitute site for this fountain that it will be really afforded.

‘Hideous structures?’ Crikey!

Over the next few weeks, there was also a bit of a spat in the letters column about the functioning of the horse troughs which were part of the fountain, with the architect himself writing in at one point. It has very 19th-century Facebook vibes.

Its fate didn’t improve: perhaps out of convenience, or perhaps out of protest, the local fishmongers started to store and clean their wares in the fountain, leaving it in a right state—and making the water rather unpalatable. Within 15 years, it had been shifted away from the High Street and down to Ropner Park.

But in 1995, the Council decided to restore it to the High Street, albeit in a different position, more or less outside M&S. I used to pop into M&S when I lived in Stockton—so absolutely nothing in this tale answers the question of why I never noticed a fountain with my birthday on it.

Since I left Stockton, it’s been moved again: in 2014, the Council relocated the fountain back to its original position in the High Street, completing a round trip that’s lasted more than a century. It no longer works as a drinking fountain, of course, and a great many of the original features such as the bronze lion heads that used to spout the water have long since been lost.

It’s strange to think that a monument which was so controversial in its day has become so beloved a century later as to be worthy of several expensive relocations despite becoming relatively dilapidated. I wonder if it will still be there a hundred years hence?