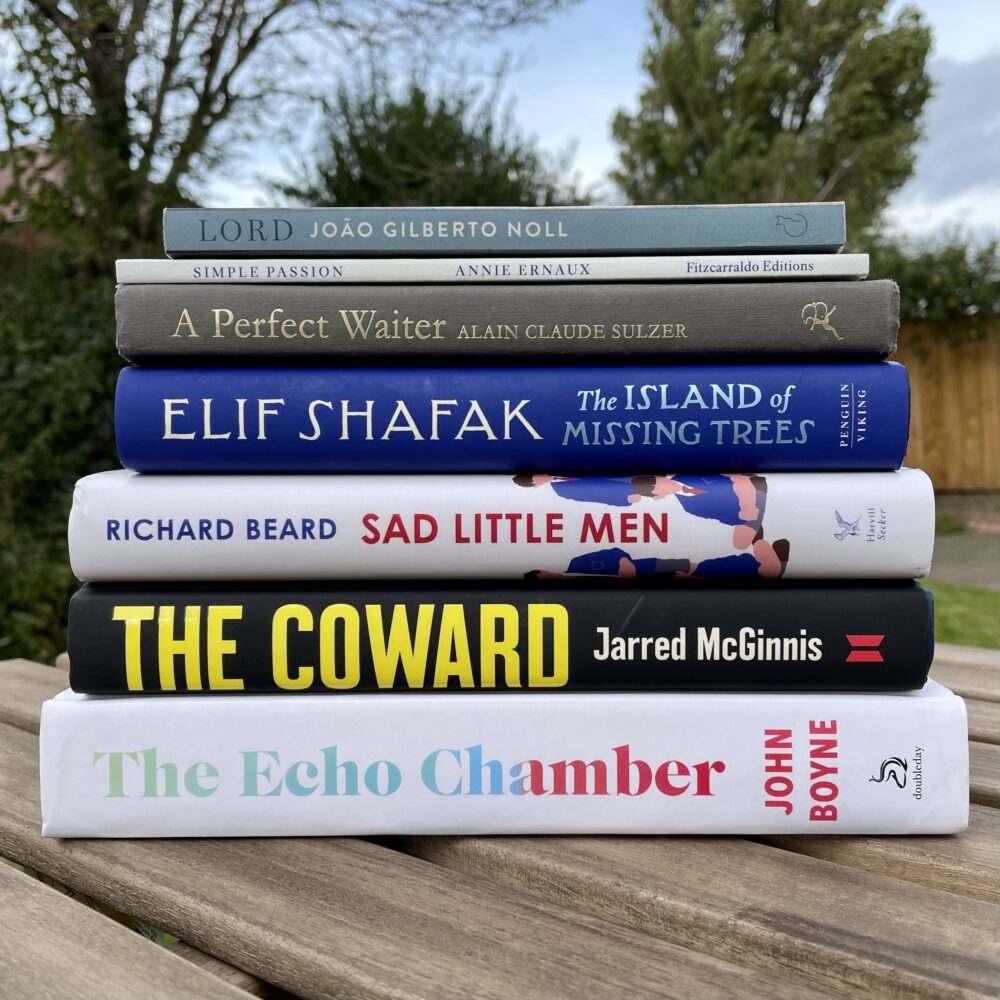

What I’ve been reading this month

There are seven books that I’ve read in October that I’d like to tell you about.

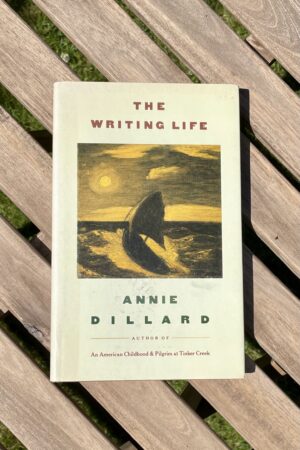

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

The first word that comes to mind to describe Elif Shafak’s recently published novel is ‘magical’. At its heart is a love story in between a Greek Christian (Kostas) and a Turkish Muslim (Defne) on Cyprus in the 1970s, just as the violent coup divided the island along those very lines. But this isn’t only a love story: it’s a story of how history echos for future generations, with the novel moving backwards and forward in time between 1970s Cyprus and 2010s London.

In the 2010s, Kostas and Defne’s teenage daughter Ada is mourning her mother’s recent death and having a difficult time of doing so, partly because of the influence of social media. Ada’s parents have fiercely protected Ada from their traumatic past in Cyprus and brought her up to consider herself to be British. The arrival of Ada’s Cypriot maternal aunt pierces that barrier (and also brings with her a whole load of charming Cypriot aphorisms).

Complex human emotions are obviously in abundance. Shafak’s masterstroke is to make one of the main narrators a fig tree: and what a fig tree! The tree itself was displaced from Cyprus to London along with the family. She (and yes, it is a she) brings her own altered perception of the passage of time, and a warm appreciation for the complex emotional relationships between the characters, and between the characters and their countries.

And the ending was breathtaking.

I’ve only read one other novel by Shafak: 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World was one of my favourite books of 2020. The Island of Missing Trees is entirely different, yet certainly one of my favourite books of 2021. I can’t wait to make my way through her back catalogue.

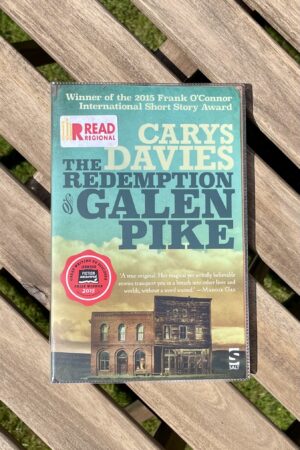

The Echo Chamber by John Boyne

Just out in hardback, this is John Boyne’s new comedic novel, which skewers society’s obsession with social media. The epigraph is from Umberto Eco, and summaries the thesis succinctly:

Social media gives legions of idiots the right to speak when they once only spoke at a bar after a glass of wine, without harming the community. Then they were quickly silenced, but now they have the same right to speak as a Nobel Prize winner. It’s the invasion of the idiots.

The main characters make up the Cleverley family, all five members of whom are irredeemably awful people. George, the patriarch, is the host of a BBC TV chat show which has been running for decades. Beverley, his wife, is nominally a writer of romance novels, though makes extensive use of ghostwriters. Alike with their three young adult children, the two hold themselves in unfathomably high esteem. Each member of the family makes use of social media for self-promotional purposes.

As with Boyne’s last novel, The Heart’s Invisible Furies, the plot is fairly ridiculous. The previous novel used a mad plot as an opportunity to string together a series of moments of high emotional drama. This novel uses one to string together a series of laugh-out-loud set pieces into one long downward spiral of farcical consequences. This is a very funny book, with lots of satirical contemporary references. (And, to note, Maude Avery—one of my favourite literary characters after her introduction in the previous novel—is referenced several times in this one.)

While this is a skewering of social media, it’s hard not to notice that social media delivers justice in the book, albeit by perverted misguided means. Through that authorial decision, Boyne leaves some interesting questions to ponder, rather than just writing off the whole medium.

I thoroughly enjoyed this.

Sad Little Men by Richard Beard

This recently published polemic against England’s private boarding schools for boys had me riveted from start to finish. This book is a reckoning with the emotional and character damage inflicted on Beard by being sent off to boarding school at the age of eight. It is also a condemnation of the impact of these schools on the country at large, given the astonishing proportion of senior figures in public life who share this background. This includes twenty-eight of the last thirty-two Prime Ministers (an astonishing statistic, even if the school lives of people born in the early 1800s ought to have little relevance to a twenty-first century argument).

This isn’t a balanced book: it is passionate, angry, withering, and all the more readable for it. That said, it is written with enough subtlety to allow us to feel sympathy for the immediate ‘victims’ as children. This is no mean feat given the illustration of the devastating, sometimes deadly, consequences for the rest of us as their adult sense of confidence and entitlement outstrips their competence.

While not discussed in the book at any length, this made me view from a new perspective the frequent political talk about ‘British values’—a soundbite often used but rarely defined. I’ve often thought that it’s essentially a dog whistle for racism. However, Beard’s book made me reflect that it perhaps has a whole other layer, recalling the perverted ‘values’ of class preservation and emotional repression that seem associated with these institutions.

The Coward by Jarred McGinnis

This recently published semi-autobiographical first novel by Jarred McGinnis opens with the main character in his mid-20s waking up in hospital following a car accident. He learns that his passenger has been killed and that he has suffered spinal cord damage which has rendered his legs paralysed. From there, McGinnis follows the story forward, to find out how Jarred learns to live with his disability. In alternating chapters, we also follow Jarred’s childhood in a violent home, and his reaction to his mother’s death early in his life.

What emerges is a portrait of a complex man, flawed in myriad ways and—maybe like us all—affected in profound ways by both his upbringing and life events. In particular, Jarred’s changing relationship with his father is explored: having run away from his alcoholic father and having not spoken for several years, his accident means that he ends up living back in his childhood home with his father caring for him again.

This is a book of complex and ever-changing relationships, filled with characters which feel real and multi-faceted. Somehow, despite the darkness, the book feels somehow up-lifting. It is also hilarious, filled with dry wit and very dark humour.

This was off-beat, moving, tender and laugh-out-loud funny.

Lord by João Gilberto Noll

I read Edgar Garbelotto’s 2008 translation of this short and very strange 2004 novel about a Brazilian writer who comes to the UK at the invitation of a Londoner. The protagonist is confused from the start, and descends into further confusion as the novel progresses. It’s always dangerous to diagnose a fictional character, but this seems to be a portrait of some sort of dementia.

In essence, this is a very readable study of what it is like to lose your sense of person, place and time—involving a surprising and perhaps disturbing number of casual sexual encounters. There are several points where it is unclear whether the narrated events are simply confections of the protagonist’s confused mind, or whether they have some basis in the novel’s reality.

This is precisely the right length, in that it can easily be consumed in a single sitting and doesn’t drag to the point that the confusion just begets reader frustration. Instead, the novel is rather reflective and thought-provoking.

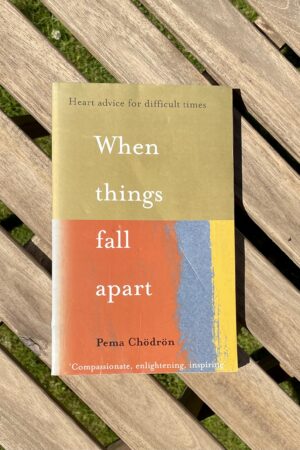

Simple Passion by Annie Ernaux

I read Tanya Leslie’s 1993 translation of Ernaux’s 1991 autobiographical essay about the passion she felt during her affair with a married man. I picked this up after seeing Eric’s Lonesome Reader review.

Choosing to try to translate the overwhelming intensity of feeling into a short book is an interesting enterprise. The autobiographical nature of the work also means that there is a superimposed layer of societal judgement on Ernaux’s essay, which she tries to disregard but perhaps concentrates on more as a result of the attempt.

I particularly liked Ernaux’s honesty in exploring the darker aspects of her passion: even very intense positive feelings have their immediate downsides, as does the longing between encounters. All-consuming feelings consume the positives as well as negatives.

A Perfect Waiter by Alain Claude Sulzer

I read this 2004 novel in its 2008 English translation by John Brownjohn. I had picked this book up having seen several reviews which compared it to Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, which is one of my favourite novels.

Sulzer’s novel is mostly set in 1930s Switzerland, where Erneste works as a waiter in a grand hotel. He has a passionate affair with a younger waiter, Jakob, and their perceptions vary as to the significance of the relationship. The novel is narrated from the perspective of Ernest as an older man, looking back on his time with Jakob after the latter has re-established contact after many years.

To me, this book shared few similarities with the Ishiguro novel. The main theme of Ishiguro’s novel is of regret at a life spent in service of the wrong ideals. The main theme of Sulzer’s novel is the limits of the extent to which we can ever know the lives and minds of other people. In theme and emotion, the two are fundamentally different, and I’m not sure the comparison is fair or helpful.

The writing was also less good: Ishiguro’s novel was evocative of its setting and time, whereas I didn’t find Sulzer’s transporting, more because the prose seemed humdrum than because the setting was unremarkable. Ishiguro’s novel clouds deep attachment in the language of restrained period ’Englishness’ whereas Sulzer’s novel reads as just a little oddly detached from his central characters.

This was just a bit disappointing, but perhaps the comparison meant that it was always destined to be.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Alain Claude Sulzer, Annie Ernaux, Edgar Garbelotto, Elif Shafak, Jarred McGinnis, João Gilberto Noll, John Boyne, Richard Beard.