I contain multitudes… and they don’t share a login

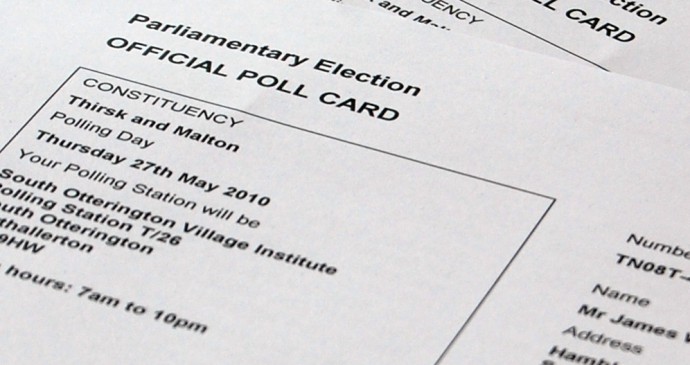

Back in March, James O’Malley wrote about the UK Government Digital Service’s (GDS) ‘One Login’ and the conceptually related Government ‘tell us once’ service. The thesis behind these services is that the Government should appear essentially monolithic from the perspective of a UK resident: information should be extensively shared across agencies, and if one updates one’s details with one agency, that update should propagate across the rest.

I agree with much of this: there is a lot to be said for simplifying interactions with Government. However, one underplayed cost is how linking data across services reduces individuals’ control over their own information. This can create murky trade-offs and unintended consequences.

To give one example: I know of a public sector organisation in the health field that went all-in on ‘one person, one record’. Superficially, this made a lot of sense, as it makes contextualisation much easier if you can see every interaction an individual has had with the organisation in a single list. _Except_… that’s not really how life works. If a journalist contacts that organisation, should that professional query really be stored alongside their personal medical data? The same applies to other professionals, say a headteacher contacting the service for advice about a pupil. Most people would have a reasonable expectation of a ‘firewall’ between personal and professional interactions, but that’s the antithesis of a ‘one person, one record’ approach. This led to a load of workarounds—appending people’s profession to their surname to create distinct ‘professional’ records, for example—that ultimately made the underlying data worse.

James cites Google as an example:

If you update your address on Gmail, you don’t need to then go and do the same thing separately on Google Maps, Google Drive and YouTube – all of those other services that are owned by the same company, and updating one will update the rest.

Yet, viewed from a different angle, this is a clear counter-example: many people have multiple Google accounts to keep their personal and professional lives separate, and they reasonably expect to update each one independently. When the Government ties all interactions to a single real-world identity, that separation becomes impossible.

‘Tell us once’ can quickly morph into ‘tell the entire state at once’—and this is often undesirable. For example, we offer free tuberculosis treatment to everyone, regardless of whether they are entitled to NHS care, because this is the best way to protect the public. This means that there will be people in the country illegally who are sharing personal information, like their address, with the NHS. If we link that data up with the Home Office, the net effect is to prevent people from accessing treatment for an infectious disease—thereby increasing risk to the public. We’ve been here before, and not that long ago.

Similarly, you might register a particular, private phone number for your interactions with services where you need a reasonable expectation of privacy—for example, if you’re reporting a safeguarding concern about a member of your family. Disaster might follow if all of your different phone numbers are thrown into a single identity—or, more likely, services find workarounds and store phone numbers in unexpected places, which exacerbates the very problem the data sharing is meant to solve. It becomes very difficult for anyone to reliably update all of their data, even within a single service.

James uses the word ‘citizens’ five times in his article. I feel a certain sense of trauma when I hear that word used in this way, borne from experience during COVID. This terminology seems to be the default within GDS. People who live in the UK but who are not citizens often have more frequent and complex contact with the Government than citizens, yet the service frequently defaults to terminology that excludes them. That feels revealing.

One would hope that the social contract is about Government giving the greatest support and most careful thought to the neediest, the most vulnerable, and the most marginalised. Yet, at least from my far-away vantage point, it often reads as though Government technology conversations begin with ‘let’s make this easier for people like me’.

So, while the direction of travel is probably right, it’s an area that needs careful thought and planning. We need to be open about the fact that ‘convenience’ often comes at the cost of personal control over data. This trade-off might sometimes be justified, but it deserves far more scrutiny than it currently receives. These kinds of changes often have unintended consequences—especially for the most vulnerable in society—and the first duty of any Government ought to be to put those very people first.

The image at the top was created with GPT-4o.

This post was filed under: Technology, James O'Malley.