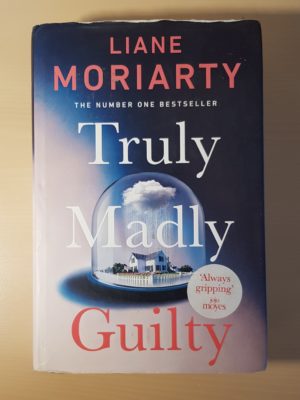

What I’ve been reading this month

I’ve five books to mention this month, four of which were published recently.

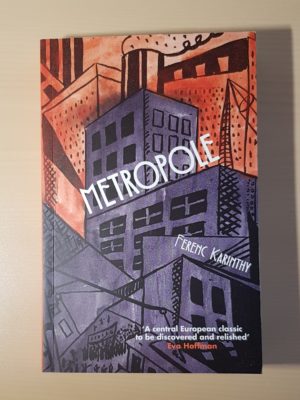

The Union of Synchronised Swimmers by Cristina Sandu

This slim Finnish novel was translated by the author and published in English in 2019. The main characters are six young women on a Soviet but stateless piece of land between two rivers and working in a cigarette factory. They discover that they have a talent for synchronised swimming, and enter an international competition.

The novel interleaves their joint story up to the competition with individual chapters focused on each of the swimmers after the competition. The whole thing is written in a very sparing, subtle style, which really only hints at a theme of multiculturalism and the difficulty of leaving behind our formative experiences.

At just over 100 pages, this was a quick but very worthwhile read. I didn’t read the blurb until I’d read the book, and this is one of those times when I was especially glad: I think it gives far too much away.

Chums by Simon Kuper

In his 2019 diary, following the election of the current Prime Minister, Alan Bennett wrote “It’s a gang, not a government.”

Kuper’s book serves to demonstrate the surprising degree of accuracy in the caricature of the current Government as a gang of privileged university friends playing political games. It also explores the degree to which this has been true in the past, and highlights the unhealthy degree to which our political classes have been drawn from a narrow background. His particular focus is on Oxford University, and specifically the arts and humanities degrees at that University. (I didn’t previously know that, traditionally, the upper classes look down upon science degrees as too ‘practically useful’.)

It was genuinely remarkable to realise that of the fifteen post-war Prime Ministers, only one (Gordon Brown) exclusively attended a university besides Oxford. Though admittedly, three didn’t attend university at all.

It’s not long since I read Richard Beard’s Sad Little Men, an angry account of the damage inflicted by private boarding schools, which skirts around similar territory. The tones of the two books are notably different: while Beard is viscerally angry, Kuper feels more inquisitive. He also comes up with some interesting suggestions on how to address the problems he identifies.

I’m glad I read this.

The Palace Papers by Tina Brown

This is absolutely not my usual kind of thing, but the combination of an unavoidable recent press launch of the book and the royal fervour surrounding the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee meant that it caught my eye. Tom Rowley’s recommendation in his weekly newsletters was the final push to click through and buy it.

The book focuses mostly on the relationships between Charles and Camilla, William and Catherine, and Harry and Meghan. Brown also covers Andrew in some detail.

The tone is waspish and gossipy, and the near-600 pages flew by. It’s clear that Brown has her favourites among her subjects, and I spent much of the time wondering how much of what I was reading could possibly be true, but I still found that I rather enjoyed it.

There were some pop culture references that were beyond me (“It was like Sean Penn in the old Madonna days”) and some strange commentary (“her hair never presented any unsettling surprises”), but this added to the gossipy charm. But I could have done without the hypocritical reporting in gruesome detail on events that had unsettled the family, followed by seeming chastisement of the press for the very reports the book repeated.

It’s not my usual cup of tea, but I downed it pretty quickly regardless.

Nothing But The Truth by The Secret Barrister

This is The Secret Barrister’s recently published third book. This volume focuses on an anonymised account of the barrister’s training at law school and through post-graduate training and their first few years at the bar. It is written in a similarly ironic, amusing style to the earlier books.

I enjoyed this, but less than the earlier books. The themes, especially of the under-funding of the justice system, are worthy. Reminding us of them is probably a valuable service, but it is also repetitious. I don’t think this book had anything new to say on the subject.

The discussion of the social makeup of the legal profession was more interesting: it reminded me countless similar discussions about the medical profession. It seemed as though the barriers to social diversity and inclusion remain even higher in the law than in medicine.

I’d still recommend The Secret Barrister’s books, but I’d recommend reading the earlier volumes first.

Elizabeth Finch by Julian Barnes

I bought this on publication because I’ve enjoyed a number of Barnes’s previous novels. This slim story is about memory, perspective, and the need to constantly re-examine history to truly understand it… or rather to continually misunderstand it, as Barnes might have it. A theme he returns to several times is that history must be misunderstood.

The titular character is an idiosyncratic lecturer in ‘culture and civilisation’, and our narrator is an adult learner who attends one of her courses. He strikes up a relationship—a friendship, perhaps—and ultimately becomes her biographer. A large section of the book is taken up by the narrator’s student essay on Julian the Apostate, which I found to be a slightly odd choice that took the wind out of the narrative sails.

I also struggled a bit with the eponymous Finch: at the start of the novel, we’re told that searching the internet for information about her life would be fruitless and would turn up no more than two out of print books. She was ‘not in any way a public figure.’

Yet later in the narrative, we’re told that she has written for the London Review of Books and been widely criticised in the media for a talk she gave at one of their events. This is surely contradictory: but I didn’t get the sense that we were supposed to judge our narrator as unreliable on basic facts. So, this confounded me, and really I wonder if I’ve completely misunderstood some key point about this book.

Barnes’s writing is as beautiful as ever, and I particularly the first part of the book, but by the end I felt more mystified than satisfied.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Cristina Sandu, Julian Barnes, Simon Kuper, The Secret Barrister, Tina Brown.