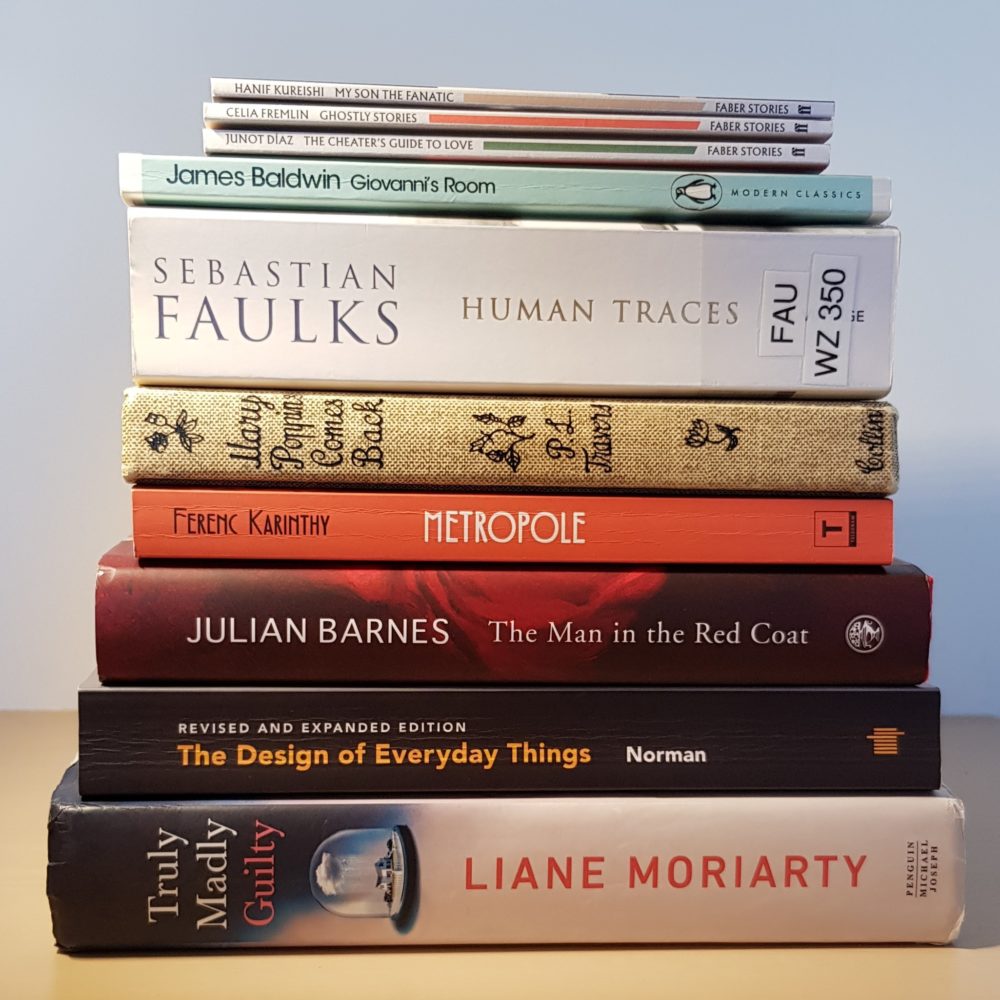

What I’ve been reading this month

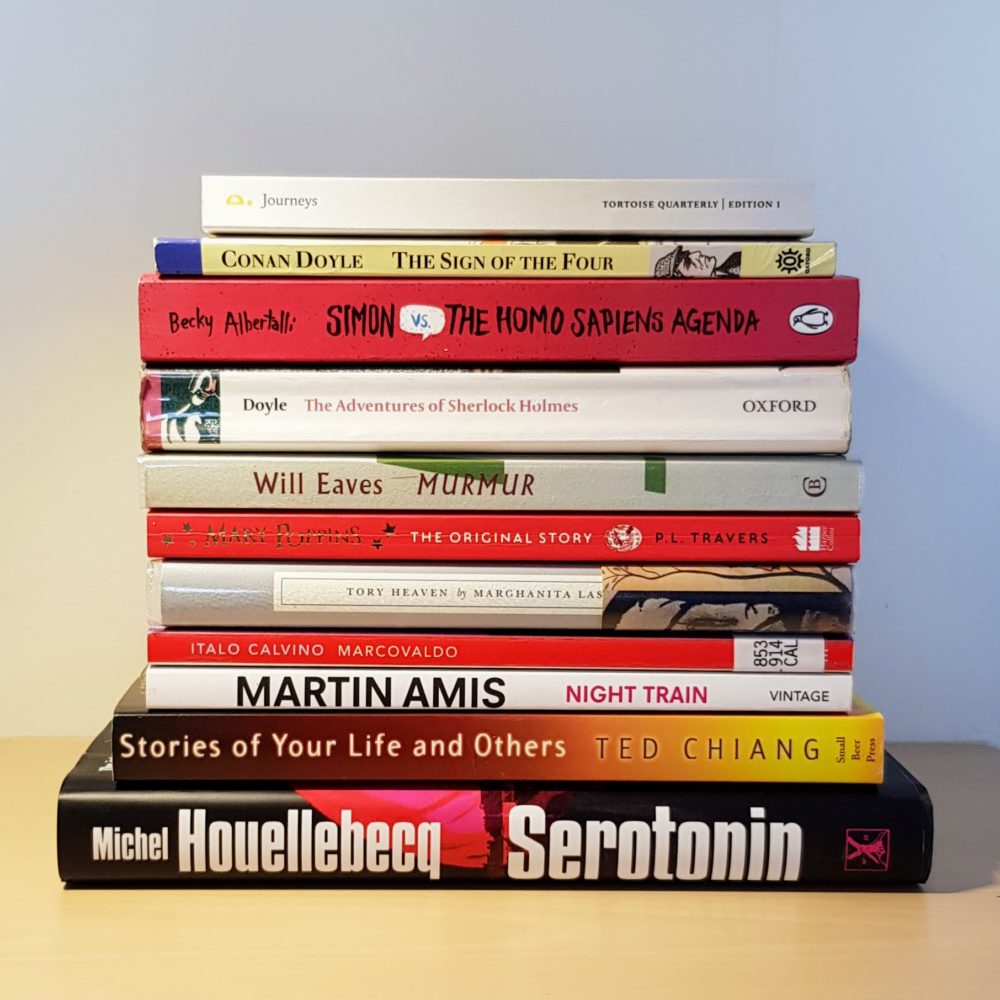

It’s been a strange month in the real world, to say the least. Nevertheless, I’ve got ten books to tell you about, all of which offered a little escapism.

Human Traces by Sebastian Faulks

I picked up this 2005 novel as it was recommended by my friend and esteemed work colleague Julie. In short: it was right up my street and I loved it.

The novel followed the lives of two doctors, from their late 1800s childhoods through their careers as early specialists in psychiatry to their old age. They set up a clinic together despite developing contrasting theories as to the causes of and treatments for mental illness, and their intellectual differences both bound them together and drove them apart.

This novel was perfect for me because Faulks skilfully wove together fictional biography with medicine, psychiatry, travel, the thrill of early scientific discovery, moral complexity, interpersonal relationships, love and philosophy—all things I really enjoy reading about. The sometimes lengthy exposition of early psychiatric theory in the book is often singled out as a point for criticism, but I found it fascinating. I was completely absorbed into the world Faulks created.

The edition I read ran to 786 pages but felt far shorter. This is a book which I will remember for a long time.

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

This novel was thoroughly depressing and heart-breaking and brilliant. First published in 1957, Giovanni’s Room followed David, a young American who lived in Paris and who awaited the return of his fiancée from her travels in Spain. He fell into an intense romantic relationship with a barman and things went downhill from there.

Really, this was a book about personal identity, guilt and the complexity of living with love. Despite the huge shifts in societal attitudes to sexual identity since the 1950s, the plot didn’t feel at all dated. The themes were universally applicable.

Baldwin’s writing made this feel absolutely complete despite it running to only 157 pages.

Mary Poppins Comes Back by PL Travers

First published in 1935, this was the second in the series of books by PL Travers featuring Mary Poppins. It had a similar structure to the first, with ten chapters each giving a reasonably ‘standalone’ account of some sort of adventure concerning Poppins and the Banks children.

I know this book was written for children, but I really enjoyed it. Poppins was a fascinating antihero of a character, not only possessed of unexplained magical powers (unless it was all in the children’s imagination) but also acid-tongued, cold and vain, with only occasional passing hints at underlying sentimentality and perhaps even love. As with the first book, there were some truly dark scenes in this volume which seem almost tailormade to give children nightmares.

Even after reading only the first two books, I can easily grasp why Travers had such a negative reaction to Disney’s treatment of Mary Poppins as a character: Disney’s saccharine singing source of warmth and comfort is certainly not Travers’s vision. And Travers’s vision is much more interesting.

The Design of Everyday Things by Donald A Norman

This was originally published as “The Psychology of Everyday Things” in 1988; I read the “revised and updated” 2013 edition.

This book made me think differently about what “design” means. I had expected this to be a book about the physical properties of man-made objects, which I suppose it was at heart, but Norman’s scope for the book included all sorts of stuff. For example, there was discussion about the relevance of design to investigation of errors and how best to manage “design” projects.

This book felt in parts more like practical philosophy than a textbook on product design. My job as a public health doctor doesn’t really involve designing anything and yet there was a lot of transferable content in here. Norman also added quite a bit of humour to the subject matter.

I had expected to enjoy this book because it would make me think differently about everyday objects. It achieved that and I took away much more besides.

The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes

I had mixed feelings about this.

Barnes’s latest book was an account of the belle époque centred on three main characters, including the eponymous Samuel Jean Pozzi, who was a pleasingly complex character. The problem with this book—to the extent that there was one—was that I just couldn’t really bring myself to care about this historical period. I’m not a fan of historical fiction, and while this was fact rather than fiction, I struggled to find any real interest in the history.

But Barnes is such a brilliant writer that this almost didn’t matter. I particularly liked his frequent reflections on the process of writing a historical account, which were deftly woven into his narrative. And while I couldn’t summon much enthusiasm for the history, Barnes’s own enthusiasm shone through in every line. Barnes also gives frequent and interesting commentary on portraits of the characters, often playfully contrasting his account with those of the gallery labels.

I suppose I enjoyed reading this book whose main subject matter was not of particular interest… if that makes any sense at all.

My Son the Fanatic by Hanif Kureishi

This short (29 pages) story was first published in the collection Love In A Blue Time in 1996; I read the recent Faber Stories standalone edition.

Kureishi explored the father-son relationship, as Pakistani-American immigrant Parvez struggled to understand his son Ali’s development of a strong attachment to Islam. To begin with, Kureishi played up the generational and East-West clash for comedy, but the characters’ estrangement became more serious and dramatic over time.

I liked this because it provided food for thought in terms of intra-familial culture clashes and the nature of fanaticism, things that I haven’t really had cause to think about a great deal. I’m not sure it’s a book I’ll return to or which will stay with me for a long time, but I appreciated the stimulation it provided.

The Cheater’s Guide to Love by Junot Díaz

This short story was originally published in 2012 as part of a collection called This Is How You Lose Her.

The story in these 56-pages was centred on Yunior, a Dominican-American writer and university professor, who cheated on his fiancée with some fifty other women and then worked through the fallout over a number of years (much of which involved further bad behaviour). The use of second-person narration and Dominican-American dialect gave this short story a real feeling of energy and urgency, which I really enjoyed. And despite its shocking premise, this was really a book about someone discovering the meaning of love.

Truly Madly Guilty by Liane Moriarty

This novel, first published in 2016, concerned a group three couples of adult friends. It was, I suppose, a character study: it tracked how the characters developed over time as various secrets came to light and events occurred which challenged their friendship.

I picked this up because I know a lot of my friends like Moriarty’s books and my sister gave this five stars on Goodreads. I did not enjoy it, and there were a number of times where I almost gave up on reading it.

It was a long book at 415 pages, and felt longer than that. The novel had a contrived structure which jumped about in the timeline in order to add suspense, but there was no real payoff because the “secrets” were a bit humdrum.

I found almost all of the characters unlikable and the setting claustrophobic: nothing in this book strayed beyond fairly superficial observation of suburban Australian life. There was neither depth of observation nor exploration of a wider set of themes (at least as far as I could derive).

That said, clearly many people love this novel and it has been a major commercial success for Moriarty, so perhaps I’m just a curmudgeon outside of the target audience.

Metropole by Ferenc Karinthy

Published in Hungarian in 1970 and with an English translation by George Szirtes published in 2008, Metropole is considered to be Karinthy’s greatest work, and one of the novels of the century. I read it as it had been selected for inclusion in the London Review Book Box.

Despite that, it didn’t do much for me. The novel’s protagonist was Budai, a linguist who ended up in an unknown city whose language he couldn’t speak. He spent most of the book moaning and acting in a manner that felt a bit dim, all while developing a seemingly non-consensual violent sexual relationship with a young woman he couldn’t communicate with (it was ‘unconventional’ according to the cover blurb, but ‘unacceptable’ according to me).

There were some interesting allegorical ideas and, to my mind, this would make for an interesting short story. It made me reflect in particular on how much the world has changed since the 1970s, how close we all are to destitution, and how hit and miss everyone’s communication can be. It was just dull when spun out to this length.

Ghostly Stories by Celia Fremlin

This volume contained two short horror stories: The New House (first published 1968) and The Hated House (1970). These were very much ‘genre’ short stories, in that they didn’t seem to reach for anything beyond the straightforward ‘ghost story’.

Neither did much for me: while competently written and easy to read, I found them bland and forgettable. The plots were predictable. I don’t think I’ve read anything by Celia Fremlin before, and these stories wouldn’t encourage me to seek out more of her work.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Celia Fremlin, Donald A Norman, Ferenc Karinthy, George Szirtes, Hanif Kureishi, James Baldwin, Julian Barnes, Junot Díaz, Liane Moriarty, Mary Poppins, PL Travers, Samuel Jean Pozzi, Sebastian Faulks.