What I’ve been reading this month

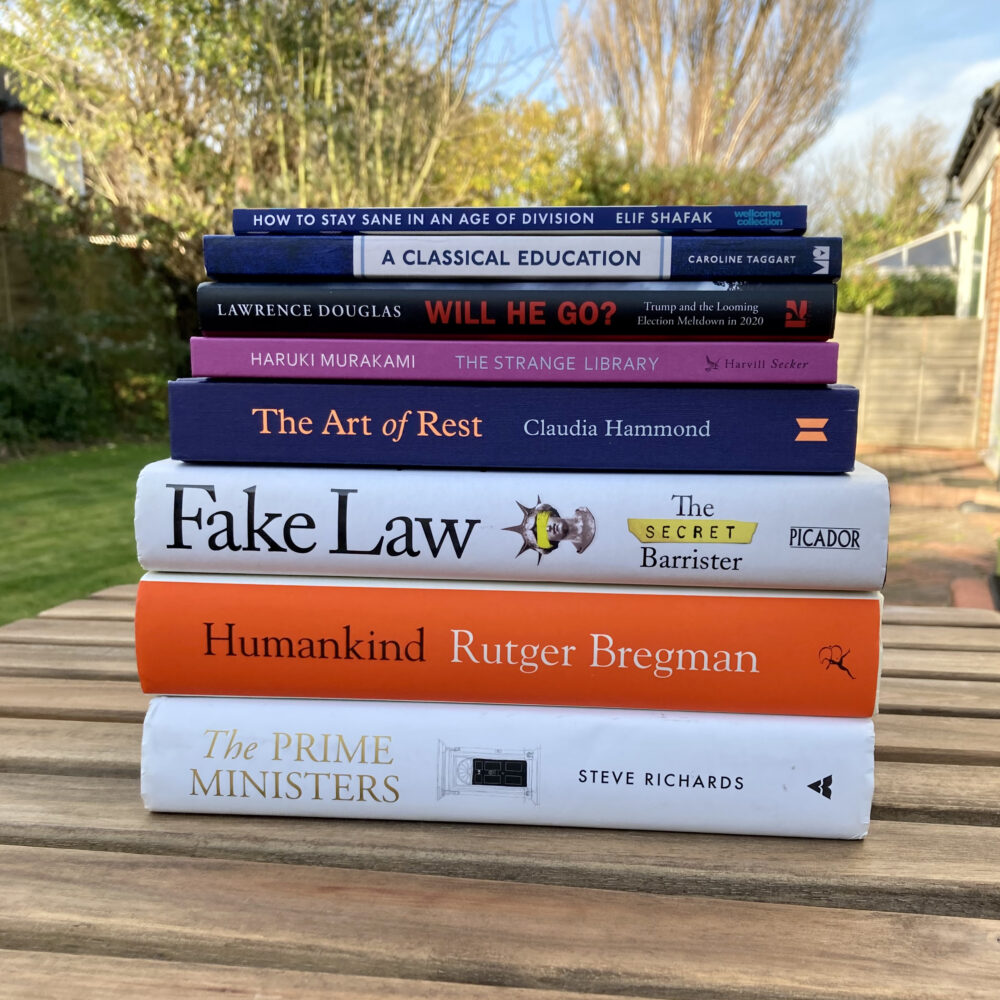

Before I sat down to write this post, I didn’t think I’d read many books this month, but it turns out that I have eight to tell you about.

How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division by Elif Shafak

I read this essay, published by the Wellcome Collection earlier this year, in one sitting. It was a passionate and beautifully written plea for pluralism, understanding, thoughtfulness, empathy and kindness. Shafak drew on her personal experiences as well as contemporary events, from covid-19 to the death of George Floyd. Shafak reminded me of the dangers of polarisation and echo chambers and the important of dialogue and understanding.

Coming at a time when all of the above seem in short supply in the world, I found myself getting a little emotional reading this. I’d thoroughly recommend it.

The Strange Library by Haruki Murakami

First published in 1983, and translated into English by Ted Goossen in 2014, this was a beguilingly strange short novel, perfect for reading in a single sitting. It’s a reflection of the book’s weirdness that there seems to be no popular agreement on whether this book is aimed at adults or children. It defies classification.

The plot concerned a young boy who visited his local City Library only to be kidnapped in the basement by an old man who wants to eat his brain. Had I known of that synopsis before I opened the book, I’d have passed on it: it sounds ridiculous and not at all like the sort of book I’d enjoy. And yet, Murakami’s writing combined with the beautiful production of the hardback lends the tale a hypnotic quality. It starts to feel like allegory—but for what?—while also being pure fantasy told in language which is entirely grounded in reality, but also somehow poetic.

This was a very short read, taking less than an hour, but was nevertheless memorable for being unlike anything I’ve ever read before.

Fake Law by The Secret Barrister

This was the recently published second volume from the Secret Barrister. It concentrated on the gap between political discourse and the reality of legislation, and the gap between media coverage of court cases and the arguments and principles actually under consideration.

I am one of those strange individuals who occasionally downloads court judgements in high profile cases, particularly those that pertain to healthcare. I enjoy diving into the gritty detail and reveling in the clarity of expression in the writing of most judgements from higher courts.

This book was right up my street. Each chapter opened with the arguments concerning a case or piece of legislation as made out by Ministers or the media. The Secret Barrister then set out the legal reality of the situation, broadened the discussion with other exemplar cases, and rounded off with a summary of the fundamental principles underlying the relevant area of law.

The book was engaging and easy to read. The Secret Barrister was very witty and persuasive in their arguments. I really enjoyed this.

Humankind by Rutger Bregman

This was Rutger Bregman’s recently published follow-up to Utopia for Realists. It was translated by Elizabeth Manton and Erica Moore.

Bregman set out to argue that most people are inherently good-natured. This struck me as a strange argument to make because it seems self-evident to me: after all, society relies on people being mostly good-natured and doing the right thing. But Bregman had a good go at making the argument that the media and culture more generally acts to convince us that most people are selfish and uncaring, but I didn’t really buy it.

This was a familiar feeling: just as I found Utopia for Realists challenging because I didn’t accept Bregman’s base assumption that societal development had stalled, I found Humankind challenging because I didn’t accept Bregman’s base assumption that most people think ill of most other people.

But just as with Utopia for Realists, I enjoyed Humankind nevertheless. Bregman discussed his ideas optimistically and cheerfully, mixing anecdote and data in a way which was very engaging. Some of the revelations about some of the famous psychological studies such as the Stanford Prison Experiment and the Milgram Experiment were new to me and enlightening.

Bregman’s observation about negativity bias and trusting people also struck a chord. If we choose to trust someone, they can undermine that trust, which is an acutely negative experience. On the other hand, if we choose not to trust someone, that decision rarely turns into an acutely negative experience, even if it may have been the worse course of action.

All things considered, I enjoyed this book, and there’s rarely been a time when a dose of optimism has been more welcome.

Will He Go? by Lawrence Douglas

Lawrence Douglas is a Professor of Law, Jurisprudence and Social Thought who has written a series of interesting articles for The Guardian over the last couple of years about the legal challenges posed by the Trump administration. In this volume, published in the spring, he sketches out ways in which Trump may have attempt to cling on to the presidency, even though the election result was not in his favour.

I read this right at the start of the month, in the run up to election day. Beyond the specifics of the current election, Douglas gave an illustration of how the procedures laid down in the US Constitution and subsequent law are open to abuse by malicious actors. As a British reader, it was interesting to compare the flaws between the codified US system and the haphazard traditions of the UK system for elections, especially as devolution moves the UK ever closer to a federal system with all of the unresolved constitutional questions that raises.

Douglas’s partial argument for the abolition of the Electoral College didn’t win me over: while I appreciate the flaws and insecurities of the system as it stands, I’m not sure it is reasonable in a federal system for the President to be elected by popular vote alone, and so I’m not convinced that abolition, as opposed to reform, is the right approach.

This was a quick and absorbing read, even if the more extreme possibilities it covered didn’t come to pass (or at least haven’t yet).

A Classical Education by Caroline Taggart

Published in 2009, this was Taggart’s short and lighthearted book on Greek and Roman history, with a concentration on bits which are particularly relevant to modern life. After a somewhat slow start rehearsing the meanings of common Latin phrases, I found myself bouyed along by Taggart’s humour and light touch.

I didn’t do much history at school, dropping it well before GCSE. I did study Latin for year, after which the school stopped offering it and I was transferred to Home Economics instead. And I’m not a big reader of the ancient classics.

All of this meant that much of the content of this book was stuff I knew once a long time ago, or have a cultural awareness of without really knowing the background. As a result, I found this light-hearted recap quite fun… but those who are better read than me might well find it very lacking!

The Prime Ministers by Steve Richards

This was Richards’s 2019 book reflecting on the leadership of the nine Prime Ministers from Wilson to May. There is now an extended revised edition also covering Johnson (which is the one I’ve linked to), but I have the original version.

I had mixed feelings about the book. After a lengthy introduction, it was structured chronologically, with roughly forty pages dedicated to each leader. Each profile was readable and interesting, and these struck me as broadly balanced appraisals.

However, I thought that his critical analysis and comparison of the leaders was a little broad-brush: I’m not sure I needed this book to tell me that early elections are dangerous or that Prime Ministers tend to have a honeymoon period where those with a strong idea of what they want to achieve can get a lot done with limited opposition. I had hoped for a little more.

The Art of Rest by Claudia Hammond

This was Claudia Hammond’s 2019 book which chatted through each the ‘top ten’ most restful activities as determined by a large survey of members of the public.

This was light and fun, with plenty of humour and personal anecdote. Hammond gave a spirited argument for taking rest more seriously, which felt timely for me given that the pandemic has left me a bit swamped with work! I liked Hammond’s “whatever works for you” approach to writing about the topic, which was refreshing given that so many books on related topics are so prescriptive. Her discussion of mindfulness was particularly grounded in realism—it works for some people, it’s not for everyone, and other activities can be just as beneficial.

Hammond presents and contributes quite a bit on Radio 4, including presenting “All in the Mind”, and the tone and content of this book reminded me of a typical series of Radio 4 documentaries—interesting, light and witty, but necessarily lacking the depth and rigorous analysis of more formal coverage of the topic.

I enjoyed this book, but didn’t come away from it thinking that I’d covered much new ground.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Caroline Taggart, Claudia Hammond, Elif Shafak, Haruki Murakami, Lawrence Douglas, Rutger Bregman, Steve Richards, The Secret Barrister.