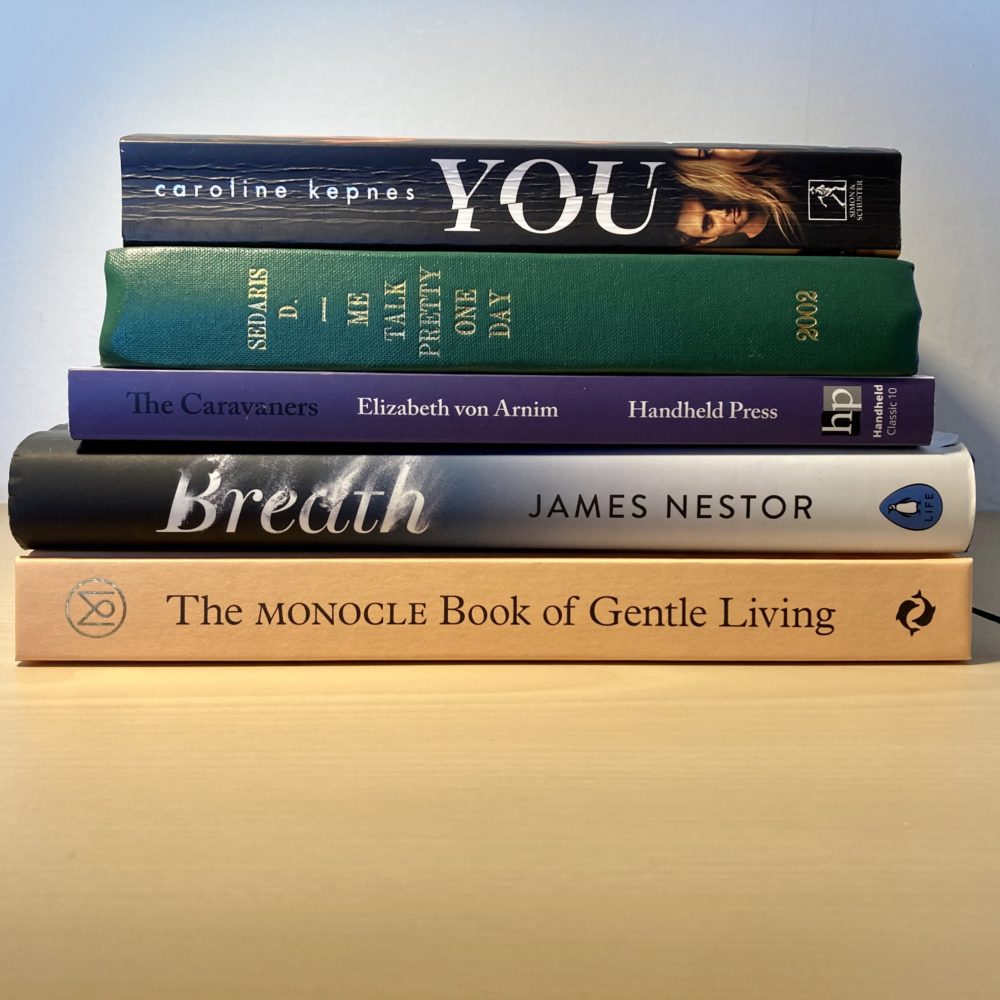

What I’ve been reading this month

I’ve read some really good books this month, and also some I liked a little less…

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart

The 2020 Booker Prize winner was, for me, a Christmas present from Wendy. It is one of those books so universally praised that it doesn’t really matter what I write about it, because the tonne of critical and popular opinion far outweighs the thoughts of a person on the internet.

For what it’s worth, I thought it was brilliant. It is the story of the relationship between young Shuggie Bain and his alcoholic mother Agnes. It follows them while Shuggie is growing up, from the age of five to fifteen, against the backdrop of impoverished Glasgow in the 1980s.

It has everything: deep characterisation, moving plot, social commentary, beautifully lyrical writing, profound insight, and more. It is superb.

I’m reminded of Jeffrey Archer whinging through one of his characters that literary prizes are never given to “storytellers”: this book conclusively proves him wrong.

There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness by Carlo Rovelli

Published in English last year, this is physicist Carlo Rovelli’s collection of newspaper and magazine articles, mostly from Italian publications over the last decade and translated here by Erica Segre and Simon Carnell. As the author says in his preface,

the pieces collected here are like brief diary entries recording the intellectual adventures of a physicist who is interested in many things and who is searching for new ideas—for a wide but coherent perspective.

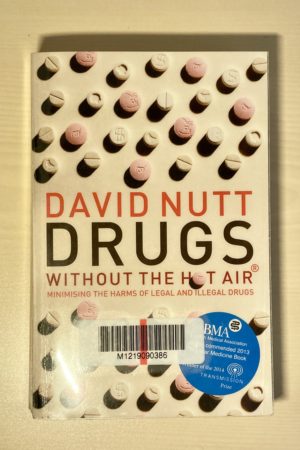

I thoroughly enjoyed this, from the columns on (what seem to me to be) minutiae of physics to the wider social and cultural commentaries, though the latter held more appeal for me. Rovelli writes engagingly and insightfully on everything from the covid pandemic to activism, and from his experiences taking LSD to his atheism. There is always something interesting about hearing people with a huge amount of knowledge and understanding of one area of life applying their perspective and approach to something different… though the three-part essay on black holes also sparkles and his tribute to Stephen Hawking moves.

I haven’t read any of Rovelli’s books before now (despite them selling in their millions), but the quality of his writing and the clarify of his imagery has got me adding them to my “to read” list.

Levels of Life by Julian Barnes

This is Julian Barnes’s 2013 genre-defying short book. It consists of three essays which are thematically connected in myriad unexpected ways: ‘The Sin of Height’ is a biography of the first aerial photographer, Nadar; ‘On the Level’ is a fictional romance between adventurer Fred Burnaby and actress Sarah Burnhardt; and ‘The Loss of Depth’ is memoir, dealing with Barnes’s experience of grief following the death of his wife.

Altogether, this makes for an exceptional portrait of love and grief. It is deeply moving and feels at times painfully honest, and even has the occasional sparkle of humour. It feels both raw, yet also thoughtful and considered. It deepened my understanding of both love and grief.

It’s no secret that Barnes can write, but it is almost impossible to grasp how he covers such expansive territory with such emotional depth in only 128 pages. Exceptional.

Banking On It by Anne Boden

Anne Boden, founder of Starling Bank, recently published this book about the experience of launching her own bank. Through the press, I’ve followed the story of Starling and it’s competition with rival Monzo over a number of years: indeed, I am a Starling customer. I picked up this book as I was keen to learn more.

This turned out to be a real page-turner, giving a lot of insight into what it is like to develop a seed of an idea into a huge business. Boden, a woman in her 50s from Wales, is not the typical model of a financial technology entrepreneur, and faces a number of challenges as a result of her “outsider” status and her desire to challenge the status quo of the banking world. The book opens with the story of her taking her final job in traditional banking as Chief Operating Officer of AIB, and her decision to take on a job which she knows will be unpleasant yet extremely challenging sets up many of her persistent character traits.

Boden reflects at length on the transition from working as a senior banker in traditional firms to setting up her own business. Boden openly discusses her strength and weakness, and the missteps she has made along the way. It was also interesting to have some insight into the regulatory processes that accompany setting up a new bank, all of which were new to me.

Boden talks in some detail about the events which led co-founder Tom Blomfield, along with other senior members of staff, to leave Starling and form a rival bank, Monzo. Clearly, Boden can only ever give her own side of the story, she couldn’t avoid discussing this pivotal point in the story of her bank, and she couldn’t have foreseen future events; but equally, in early 2021, it is a little uncomfortable to consider Boden’s one-sided and unflattering portrait of Blomfield in the light of his post-publication resignation from Monzo and disclosures in recent weeks about his mental health. I suppose this is something of an occupational hazard when writing about fairly recent events involving real people.

Nevertheless, I enjoyed this peek into a professional world which is so far removed from my own, and Boden’s humour combined with the pacy plot kept me racing through the pages.

The Future of Stuff by Vinjay Gupta

This is the third essay I’ve read in the Tortoise Media FUTURES series, and my favourite so far. Written by Vinjay Gupta, the violinist (and social activist), it is a hopeful account of how our behaviour around purchasing and consumption is likely to change as we become more aware of the systems that support products.

Gupta’s central argument is that we can’t just buy a widget, for example: we are supporting a much broader system which produces said widget, which might well include supporting disgraceful labour practices on the other side of the world. As the world moves towards greater information flow and transparency, and—crucially—as we get better at managing and processing that information, our perspective on purchasing is likely to change.

As a basic example: if an online supermarket were to introduce a simple site-wide filter allowing customers to opt to see only “vegan” products, that would be enormously helpful to individuals and drive sales of those products. As our social conscience moves forward, perhaps there will be similar filters for ethically produced products and so on. And as data on product provenance becomes more widely available and codified, the same data can be used for better advert targeting, and so on and so forth.

I found the argument convincing, and it’s nice to be convinced by something so hopeful these days!

Naked by David Sedaris

I’m still on a bit of a Sedaris binge, having read many of his books over the last few months. This is the earliest collection of his essays that I’ve read, published in 1997.

I found the essays in this volume to be a little more hit-and-miss than the later collections, as though he was still trying to find his style, but I still laughed frequently.

Daddy by Emma Cline

Published last year, this is a collection of ten short stories by Emma Cline. Seven of the ten have been previously published in either the New Yorker, Granta or The Paris Review.

I have previously read the author’s first novel, The Girls, which was a best-seller but left me a bit cold. I enjoyed this collection more than the novel, though the stories all shared a similar structure, consisting mostly of characterisation around an unspoken central event or situation. There’s also a theme of gender running throughout, particularly a theme of unpleasant men. Having a similar structure and a similar theme to all of the stories struck me sometimes as interesting (different facets into similar issues) and sometime as a bit dull, I think largely depending on my own mood.

The final story, A/S/L was my personal favourite, perhaps because the unspoken nature of the central fact fitted into the setting the author created so naturally. I think, though, that this collection might be better read as individual stories than as a single collection.

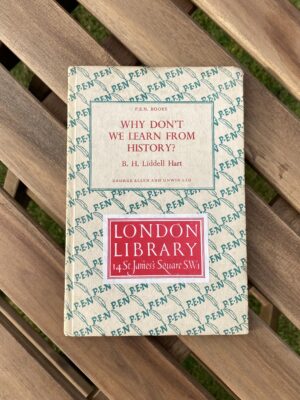

Why Don’t We Learn From History? by BH Liddell Hart

I was lucky enough to read this famous essay in an original 1944 edition.

It starts off well: Liddell Hart gives a lot of interesting theories for why we seem not to learn from history, with a central tenet being that we aren’t very good at truthfully recording events in the first place.

He then lost me for the second half of the essay by going into some detail about the Second World War and perceived problems with the Christian church, which I’m sure would be interesting to many people, but don’t seem obviously related to the titular question.

It’s only short—58 pages in my edition—so I got my effort’s worth from it anyway.

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li

This 2019 novel by Yiyun Li imagines a series of conversations between a mother and her teenage son, who she has recently lost to suicide. It is a short book at 192 pages.

My first impression of this was strong. The imagined conversations are true to life (or perhaps true to death) and interesting philosophical. The mother character writes novels, while the son was a budding poet, and there’s a lot of ‘philosophy as language’ in here: the conversation is often taken deeper through discussed reflection on the etymology of chosen words, for example.

However, my interest in this waned over time despite the short length. It felt a little emotionally flat to me, and there wasn’t a great deal of progress in the conversation. Perhaps that is intended to reflect something of the lived experience of the aftermath of a child’s suicide; I’m not sure.

It came to feel to me that the desire to dissect language as a way into the emotion was limiting rather than enlightening. Perhaps others will feel differently.

I Hate Men by Pauline Harmange

Published in English for the first time this month, this is Harmange’s 2020 essay on hating men.

Lest we think the title is just a rhetorical device, Harmange is emphatic:

I hate men. All of them, really? Yes, the whole lot of them … Hating men as a social group, and as individuals too, brings me so much joy.

Even her nearest and dearest are hated:

We need to be vigilant, we have to keep an eye on the genuinely decent ones, because anyone can stray off course, and all the more so if he’s cis, white, wealthy, able-bodied and heterosexual.

I’m a man. It’s fairly clear therefore that Harmange hates me, even though I followed her advice:

The very least a man can do when faced with a woman who expresses misandrist ideas is to shut up and listen. He’d learn a great deal and emerge a better person.

I really don’t know what to do with this book. It’s full of justifiable and passionately expressed anger. But if anger begets only hate, where does that leave us?

I’m not sure I learned a great deal, and I’m not sure I emerged a better person. I emerged mostly as a slightly sadder person, and one that’s a little less hopeful for the future of humanity now that I know that books that actively promote hatred on the basis of unchangeable innate characteristics can become bestsellers in the twenty-first century.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Anne Boden, B. H. Liddell Hart, Carlo Rovelli, David Sedaris, Douglas Stuart, Emma Cline, Julian Barnes, Pauline Harmange, Vinjay Gupta, Yiyun Li.