Warming up

Same time, same walk, two days later… and it’s no less than seventeen degrees warmer. Spring is mad.

This post was filed under: Photos, Post-a-day 2023, Newcastle upon Tyne, Weather.

Same time, same walk, two days later… and it’s no less than seventeen degrees warmer. Spring is mad.

This post was filed under: Photos, Post-a-day 2023, Newcastle upon Tyne, Weather.

This recently Oscar-nominated film by Charlotte Wells has been on my ‘to watch’ list for a while, after I saw a trailer at the cinema. It follows a depressed 30-year-old on holiday in Turkey with his 11-year-old daughter, from whose mother he has separated. It is set some time in the 1990s, I think, with camcorder footage spliced into the film at times.

Later, it is revealed that the film is from the perspective of the daughter after she has grown up. She is looking back at her memories of her dad as she reaches the age that he was on this holiday. We’re left to ponder whether her memories are accurate.

It is a very personal film, one where not much happens, but the power is in the (mostly unexpressed, mostly repressed) emotions of the piece. Paul Mescal and Frankie Corio give astonishingly natural performances throughout. Wells also plays with the cinematography in ways that underline and support the unspoken emotions: some sequences are bright and dreamlike, others have characters sometimes seen only at the edges of frames.

And yet… for whatever ineffable reason, whether to do with the film, or the conditions in which I watched it, or my mood at the time, or some combination of things… it didn’t emotionally reel me in. I felt like I was watching a film, not like I was involved in the characters’ lives. It felt a bit consciously clever to me, at a remove from the viewer.

I wasn’t quite as taken with this film as were many of the professional reviewers, but I still enjoyed it.

This post was filed under: Film, Post-a-day 2023, Charlotte Wells, Frankie Corio, Paul Mescal.

The -5°c walk to work was a shock to the system. At least, unlike this flora, I hadn’t been out in it all night. It doesn’t look as though the flowers enjoyed the chill.

This post was filed under: Photos, Post-a-day 2023, Newcastle upon Tyne, Weather.

This 2019 bestseller is tricky for me to write about because I have strong feelings in two completely contrary directions.

This book is excellent at highlighting hidden injustices faced by women around the world on a day-to-day basis. Because of my background, I was particularly swayed by the section on medical research and the fundamental problems introduced when women are excluded from studies. The lack of inclusion of women in car safety standards is also shocking, and the section on the lack of careful consideration of the needs of women in relief aid was heartbreaking.

This book is important for highlighting all of these issues. I don’t want anything else I say to take away from the fact that this is a book which deserves to be read, deserves to make people angry, and deserves to inspire change.

But there are quite a few ‘buts’.

Firstly, the style of writing is desperate. Criado Perez swings from detailed, thoughtful discussion of cited studies to hyperbolic polemic even within paragraphs. She makes statements that are patently absurd with even a moment’s thought, such as:

There is no such thing as a woman who doesn’t work. There is only a woman who isn’t paid for her work.

and:

“The Fawcett report is all the evidence we have, because the data is not being collected by government, so unless this particular charity continues to collect the data, it will be impossible to monitor progress.”

To state the obvious: there are women who do no paid nor unpaid work; anyone could continue to collect data, even if ‘this particular charity’ was closed down.

This sort of writing flows through the book, and it is problematic because it often undermines Criado Perez’s brilliantly argued case—not least because it’s often right in the middle of a paragraph that’s making the case. A good editor should have spotted this.

Secondly, I disagree with Criado Perez’s assertion that if women are the majority practitioners of an activity, then barriers to that activity are automatically a gendered issue. The obvious example here is that gritting roads rather than pavements is, essentially, sexist because women make more journeys on foot than men.

I disagree: this might have a differential gender impact, but I don’t think it is primarily a gendered issue, and I don’t think viewing it from that perspective is especially helpful. I think viewing it from that perspective is unlikely improve the overall inclusivity of the flawed policy.

Thirdly, some of the logic is distractingly unusual.

Criado Perez argues that spending money on road-building prioritises men because women more often take the bus, without any acknowledgement that buses run on roads.

Criado Perez talks about the first artificial hearts being too big for women, and them having to wait years for the technology to be miniaturised: but I’m not sure what the alternative is. Ought we not to use products only in one sex until the technology is sufficiently advanced to use them in both?

The author talks about the over-citation of male authors of research based on implicit bias, but also cites evidence to suggest that female authors are frequently assumed to be male. Obviously, while pulling in different directions, both can be true at once because not all of those cited will be unknown to the person doing the citing. But both also pull in different directions in terms of solving the problem, so it’s not clear how it advances the author’s argument.

The tortuous logic was often distracting.

Fourthly, I had a strongly negative reaction to Criado Perez’s repeated dismissal of psychosomatic symptoms, with phrases like:

Four different medical professionals thought it was in her head, that she was simply struggling with anxiety.’1

There is nothing simple about struggling with anxiety, and it is no ‘lesser’ a diagnosis than the uterine fibroids that complete the story from which I’m quoting.

Of course, misdiagnosis is regrettable, and of course, it is especially problematic that the rate of this sort of misdiagnosis is gender-patterned and of course that must be addressed. But to describe a serious—if incorrect—psychosomatic diagnosis as a patient being ‘told she was imagining it’ is also deeply regrettable, and especially so in this book given the female-skewed epidemiology of genuine psychosomatic illness.

Finally, this isn’t really a book about data gaps. It cites a few, but frequently Criado Perez concludes sections with phrases like:

This isn’t exactly a data gap, because the data does mostly exist. But collecting the data is useless unless governments use it. And they don’t.

This is really a book about non-inclusive decision-making. It’s a book that points out tragic flaws which arise when people fail to properly consider (or even monitor) the impact of decisions on all the people they affect. It’s about so much more than data gaps, and by boxing its arguments in those terms, it rather limits its own conclusions. I worry that the publisher has marketed the book in those terms because of a trend in books about data, rather than because that’s the approach that best suits Criado Perez’s argument.

As I said at the top, this is a book which deserves to be read and which deserves attention. It is worth your time. But, like many books, it’s also flawed in ways which might have you—like me—grinding your teeth. I’d suggest grinding through it.

Many thanks to Newcastle University library for letting me read their copy of this book.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, What I've Been Reading, Caroline Criado Perez.

At this time of year, along with the majority of medics, my thoughts are turning a lot to the process of reflecting on clinical practice. This is something that I think most of us do most of the time, but written reflections form a mandatory part of continuing professional development for most medics. Many of us fail to keep on top of them, and end up with a glut to write towards the end of the financial year.

I’m also currently reading Haruki Murakami’s Novelist as a Vocation. I’ll tell you more about that when I’ve finished it, but I wanted to feature this passage (actually, two concatenated passages) where Murakami is giving advice to aspiring novelists on reflecting on their everyday experiences. It’s as good a description as I’ve read anywhere of the process of reflection, and so really resonated with me.

Make a habit of looking at things and events in more detail. Observe what is going on around you and the people you encounter as closely and as deeply as you can. Reflect on what you see. Remember, though, that to reflect is not to rush to determine the rights and wrongs or merits and demerits of what and whom you are observing. Try to consciously refrain from value judgements—conclusions can come later.

I strive to maintain as complete an image as possible of the scene I have observed, the person I have met, the experience I have undergone, regarding it as a singular ‘sample,’ a kind of test case, as it were. I can go back and look at it again later, when my feelings have settled down and there is less urgency, this time inspecting it from a variety of angles. Finally, if and when it seems called for, I can draw my own conclusions.

I really liked this description, but it was Murakami’s next paragraph that completely stopped me in my tracks:

Nevertheless, based on my own experience, I have found that the occasions when conclusions must be drawn are far less numerous than we tend to assume. Indeed, the times when judgements are truly necessary—whether in the short or the long run—are few and far between. That’s the way I feel, anyway. This means that when I read the paper or watch the news on TV, I have a hard time swallowing the reporters’ rush to give opinions on anything and everything. ‘Come on, guys,’ I feel like saying, ‘what’s the big hurry?’

When Wendy and I are watching the news on TV, we frequently comment “It’s not though, is it?’ in response to opinions given by reporters who get caught up in their story’s importance. It irritates us when reporters give commentaries that a moment’s thought would dismiss: ‘this is the most serious crime of the decade,’ ‘this is the biggest political crisis since the second world war,’ ‘this is a make-or-break moment for the political party,’ and that kind of thing.

I’d never before made the connection between thinking reflectively and avoiding a rush to judgement. Now that it has been pointed out, it’s obvious—but reading the above passage was a definite ‘aha’ moment for me, a moment that allowed to see a connection between disparate ideas for the first time.

The picture at the top of this post is an AI-generated image for the prompt ‘a photo of a doctor looking pensive in a mirror’ created by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2. The mirror is a pun on the word ‘reflection,’ just in case that’s not immediately obvious. There’s nothing funnier than a joke that has to be explained.

This post was filed under: Health, Post-a-day 2023, Quotes, Haruki Murakami, Medicine.

I am nowhere near well-read enough of art to be aware of the (apparently very famous) mid-20th century Scottish artist Wilhelmina Burns-Graham. I therefore didn’t really know what to expect of this exhibition. From the title, I assumed the work would be abstract, which, as I’ve previously mentioned, is right up my street.

It turned out that this large-scale exhibition of seventy chronologically presented paintings and drawings was quite fascinating in the way it showed the development of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham’s style.

Barns-Graham’s early work was almost entirely representative: there were a lot of ‘nice’ but plain depictions of ‘nice’ by plain scenes, such as the Cornish landscape. Some of these had a rather idiosyncratic style with some bold brushstrokes, but there was nothing in this work that especially stood out to me.

Later, Burns-Graham painted and drew pictures of Swiss glaciers, which naturally have quite abstract and complex forms. Whether it was due to the hanging of the exhibition or a true reflection of reality, I could feel Burns-Graham becoming increasingly taken with abstract forms over this period. The pictures became much less representative, and much more reflective of feeling and response… much more my kind of thing.

I was very taken in by this 1958 painting, Pink and Flame, which suggested so many things to me, but most especially the warmth of a fireplace in a living room (or perhaps a kitchen?)

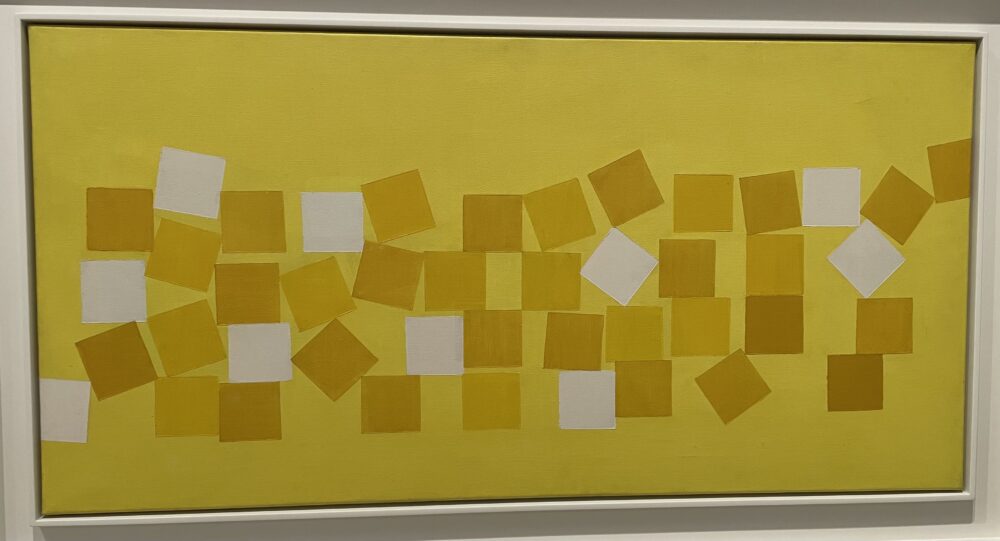

From here, Barns-Graham started to experiment with even greater abstraction, teaching me that regular geometric forms can, in fact, be even more abstract than works without clear form.

This is 1964’s Cinders, which stood out to me as a good comparison with the 1958 painting, for depicting a broadly similar thing in a much more abstracted–but more geometric–form. This slightly blew my mind, as I’ve always associated abstraction with a lack of form.

So, what I really liked about this exhibition was the way it flowed, and the way I could follow through the development of this singular artist’s work over decades. I at least had the impression that I was following her thought patterns, which made for a very successful and absorbing show.

This last work, 1966’s Bird Song, stood out to me for quite personal reasons. I find the colours in it, combined with the synaesthesic abstraction, fascinating. Looked at one way, the yellows and oranges are a celebration of spring, of everything that is positive in nature. Looked at another way, they are colours of warning, of danger, of distress.

This struck a chord with me: it’s a weird thing to admit, but I’m not a fan of birdsong. ‘How,’ you might wonder, ‘can anyone dislike birdsong?’

I just find so much of it irritating. It’s the alarm-like aesthetic of repeating sounds, often not even repeated in a rhythm that I can try to tune out. I often want the birds to shut up. It’s the bursts of birdsong that made me stop listening to Scala Radio’s In the Park each morning.

Anyway… I was just delighted that Barns-Graham captured a bit of that element in her painting, intentionally or otherwise.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: Paths to Abstraction continues at the Hatton Gallery until 20 May.

This post was filed under: Art, Post-a-day 2023, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham.

Roughly three-quarters of people seeking asylum in the UK have their applications granted, two-thirds on initial application and the remainder on appeal. These people have a ‘well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion’ in their home country.

Our Government’s outright refusal to provide safe and legal routes for most refugees to enter the country to apply for asylum means that the majority arrive though covert, unsafe means. These people come here ‘illegally’ because there is no way for them to get here ‘legally’. Only a small minority come via boat. Many die en route.

The Government says that ‘if you come to this country illegally, you will be swiftly removed.’ Without providing legal routes—which the Government has explicitly promised not to do—that statement is incompatible with providing asylum to the majority of people who need it.

Before the 2015 election, nine in ten asylum applications were processed within six months. By 2021, the proportion had fallen to one in ten, cruelly leaving traumatised people in limbo for longer than ever before and resulting in spiralling accommodation costs. The system hasn’t broken due to the weight of applications: the number per year has barely changed since 2015.

Referring to ‘stopping the boats’ is appallingly dehumanising: it’s not ‘boats’ that the government aims to prevent from entering the country, it’s people. Referring to people in dehumanising terms is the opposite of showing compassion.

According to the documents laid before Parliament, the Home Secretary is ‘unable to make a statement that, in my view, the provisions of the Illegal Migration Bill are compatible with the [European] Convention [on Human] Rights.’ In the Government’s view, ‘illegal’ may therefore apply equally to the ‘migration’ and the ‘bill.’

Those who allocate more airtime, pixels or ink to discussing presenters of the BBC’s sports programmes than to analysing the nation’s asylum policy may not be performing a true public service.

The picture at the top of this post is an AI-generated image created by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

This post was filed under: Politics, Post-a-day 2023.

This is a bestselling 2022 comedic novel about Elizabeth Zott, a chemist working in the 1950s and 1960s, who also ends up presenting a television cookery programme called ‘Supper at Six’.

Early on, I came as close as I have in a long while to giving up on a book. Garmus manages to hit quite a few of my pet hates in novels full square.

The cast of characters includes Six-Thirty, a preternaturally intelligent dog who reflects on idioms, becomes irritated by another dog’s ‘smugness’, and even overhears a phone conversation and leads its owner to a wardrobe in response. This is a novel which, at heart, is about emotional truth; I find it hard to access that when I have to suspend disbelief so frequently. Having an omniscient narrator unrealistically imbue an animal with human-like emotions reduces the impact of that same omniscient narrator telling us about other characters’ emotional states.1

Garmus also writes exceptionally clunky dialogue: this is the sort of novel where everyone speaks in complete sentences, which often also include a dose of narrative exposition. “Jesus, it’s as if you’re not familiar with TV’s tribal ways.”

Garmus also writes the plot in a way that elides time and effort, which is particularly curious when a theme of differential time and effort requirements for men and women is seeded throughout the book. Zott becomes an elite rower virtually overnight, and an accomplished television presenter in a matter of days.

But but but… I didn’t give up. Somehow, Garmus won me over, and I found myself enjoying this despite all of the above. The evocation of the treatment of women in science (and society) in the era was strong and insightful. The funny bits were frequently actually funny. The core messages were well-meant, if a little heavy-handed and preachy.

I’m not certain that I’d rush to read Garmus’s next novel, but I nevertheless enjoyed this more than I initially anticipated.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, What I've Been Reading, Bonnie Garmus.

One of my pet peeves with any play (or book or film) is when I’m told within the text what I’m supposed to be feeling. There is nothing that does quite so much to telegraph a lack of confidence in the work than to tell the audience how to respond. I’m afraid The Boy with Two Hearts falls into exactly this trap.

This is a stage adaptation by Phil Porter of Hamed and Hassim Amiri’s memoir recounting their family’s harrowing journey from Afghanistan to the UK. The family was forced to flee Herat in 2000, after the Taliban ordered the killing of the matriarch for speaking out on women’s rights. Complicating matters, Hamed and Hassim’s brother Hussein has a serious congenital heart problem.

The play follows the parents and three young children as they cross Europe, trying to reach the UK for both family safety and NHS treatment for Hussein. I saw the play in my living room via National Theatre at Home, which is never quite the same experience as being in the same room as the performers.

The staging was admirably inventive, making use of projections to allow some dialogue to take place in Farsi with translations integrated into the scene. The show was scored throughout, with a singer (and co-composer) Elaha Soroor wandering around the set providing an elegiac backing of Afghan song.

The overall effect was moving, and it brought real human insight and compassion to the topic of asylum. It is well worth watching or going to see.

But I did have issues.

Firstly, a minor nitpicky staging issue which irritated me repeatedly. We are introduced at the start of the play to the fact that the family sits in a circle to eat and talk. Because they are on stage, they are not actually sat in a circle while they are talking about being sat in a circle, presumably because we wouldn’t see much and half the cast would have their backs to us. This is fair enough, except for the fact that they then call back repeatedly throughout the play—including in the very climax—to the circle. I don’t think it works to repeatedly call back to an image that the production never quite delivered.

Secondly, and I think this is a book-to-stage translation thing, there is a problematic lack of detail in some parts. I spent much of the first half wondering what the main character’s motivations were, partly because we are told nothing of their background.

Thirdly, the big one. Don’t tell me what to feel. This is a sad play. It is also a play that highlights stunning hypocrisy in the way we treat people and the way we collectively choose to view the world. We are only happy for the NHS to treat a severely sick kid once he’s completed a life-threatening journey across a continent: how can we be so cruel? And yet, the audience is directly addressed and told that this is not a sad play, and that it is actually a play about it being wonderful that everyone looks after each other.

Issues aside—I’d still recommend it.

The Boy with Two Hearts is streaming on National Theatre at Home until 14 December.

This post was filed under: Post-a-day 2023, Theatre, Elaha Soroor, Hamed Amiri, Hassim Amiri, National Theatre, Phil Porter.

This exhibition of 150 abstract paintings from 81 overlooked female artists was exhilarating. As with surrealist art, abstract art is the sort of thing I would choose to have in my own home. I like the boldness, the depth, the way one’s interpretation shifts over time, the way you can’t quite pin it down. It is just totally my kind of thing.

As I was on my way to this exhibition, I happened upon an article about Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s design for 78 Derngate. This mentioned that Mackintosh’s designs and colour choices were dramatic to appeal to the client, who had limited colour vision. This made me wonder whether my limited colour vision is part of the reason that I enjoy big, bold, abstract art. Who knows.

I could, quite happily, have stayed all day at this exhibition, and still wanted to go back for more. I had so many favourites in that it’s hard to know which works to include in this post, but here are a few.

This is Distillation, a 1957 work by Gillian Ayres. Just look at it!

It’s apparently partly painted in household enamel and partly in oil paint. Ayres laid the canvas on the floor and poured, squirted, and brushed pain all over it, dissolving it with a solvent so that she could keep shifting it about.

Apparently, Jackson Pollock was an influence, but I care less about that than the fact I could get lost in it for days.

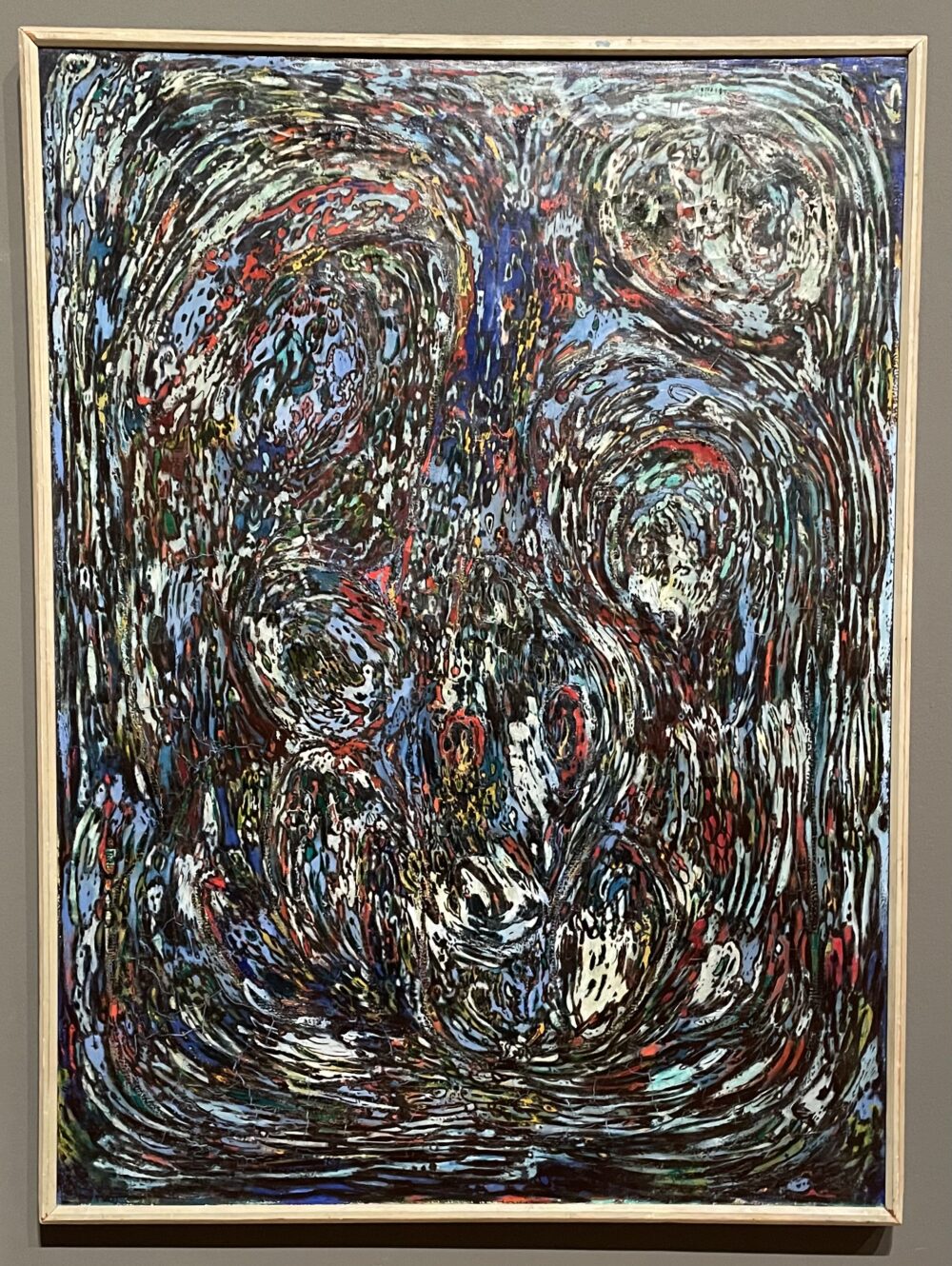

This is Myriader (myriads), painted in 1959 by Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg. It’s such an intense piece. It immediately makes me think of those days—often busy work days—where it feels like my thoughts are going faster than I can keep up with them.1 Interestingly, it was Fonnesbech-Sandberg’s psychoanalyst who encouraged her to express herself through painting, so maybe this is precisely what it represents.

These pieces are made by building up layers and layers of paint, then scratching some bits off and building them up again… which is a technique that chimes nicely with the sensation the work seems to represent.

This is Idyll II, a 1956 work by Miriam Schapiro. Schapiro based each of her works on those of old masters, recreated in her own style. I’m not sure what work this is based on, but I love how the figures come into and out of view. Sometimes, I see a small orchestra or band in this work, which is appropriate as there is something about the whole composition which seems musical to me.

This is La Nef (Interieur d’Eglise)—or ‘The Nave (Interior of a Church)—painted in 1955 by Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. This was one of the smaller works in the show. I liked this less on an immediate ‘I want that on my wall’ level, and more on an intellectual level. The more I look at it, the more it clearly is a church, or the idea and feeling of a church, with regular almost arithmetical forms but cut across with things that don’t quite fit. And isn’t that also essentially religion?

And one more, just because it makes me go ‘wow.’ This is Mary Abbott’s 1959 work, Purple Crossover.

People who actually know something about art have written rave reviews of Action, Gesture, Paint. Given that an artistic idiot like me is also raving about it, it’s certain to get busy, so buy your tickets now. It continues at the Whitechapel Gallery until 7 May, after which—at least according to the chatty lady managing the cloakroom–it’s off to France and then Germany.

This post was filed under: Art, Post-a-day 2023, Elna Fonnesbech-Sandberg, Gillian Ayres, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Mary Abbott, Miriam Schapiro, Whitechapel Gallery.

The content of this site is copyright protected by a Creative Commons License, with some rights reserved. All trademarks, images and logos remain the property of their respective owners. The accuracy of information on this site is in no way guaranteed. Opinions expressed are solely those of the author. No responsibility can be accepted for any loss or damage caused by reliance on the information provided by this site. Information about cookies and the handling of emails submitted for the 'new posts by email' service can be found in the privacy policy. This site uses affiliate links: if you buy something via a link on this site, I might get a small percentage in commission. Here's hoping.