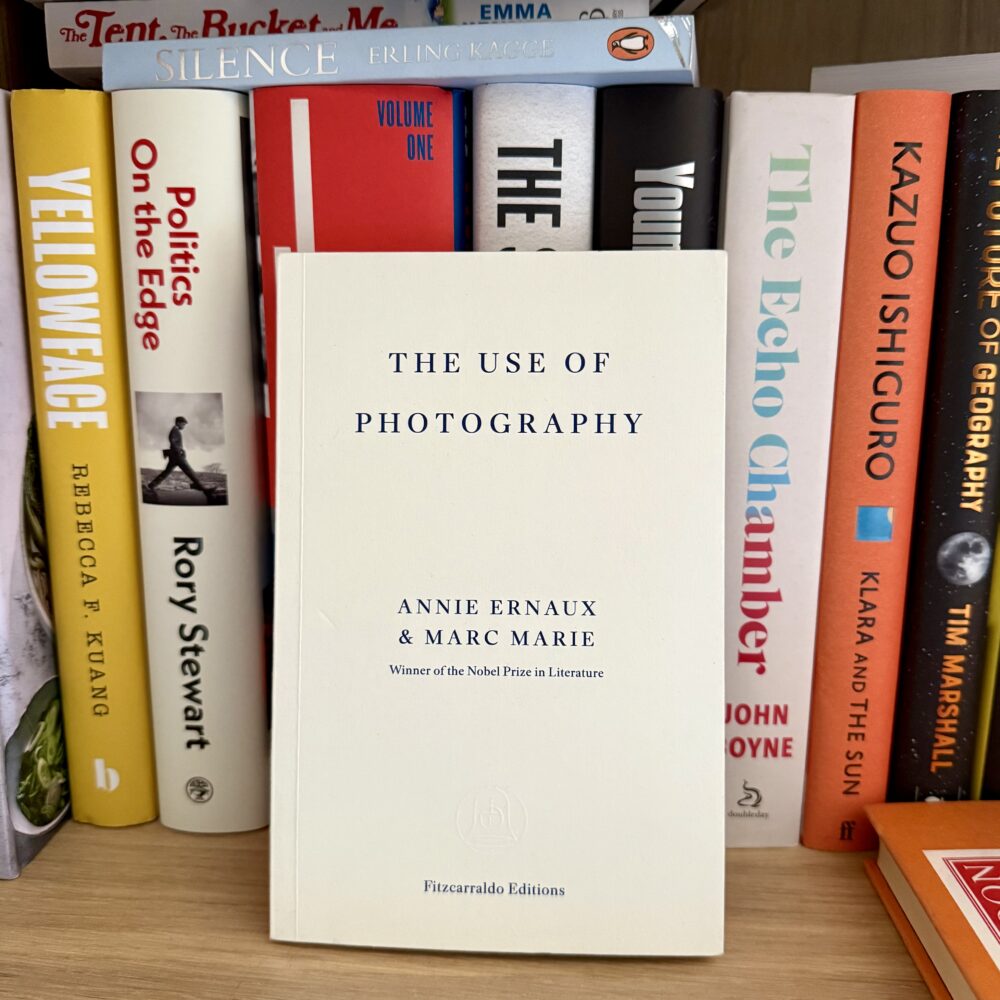

‘The Use of Photography’ by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie

I’ve long admired Annie Ernaux’s writing for its relentless honesty—her refusal to flinch from the rawest corners of human experience. That fearless openness drew me to The Use of Photography, co-authored with journalist Marc Marie and translated by Alison L. Strayer. It’s a brief, piercing book, documenting an unlikely intersection in the early 2000s of two intense experiences: Ernaux’s chemotherapy for breast cancer and a passionate affair with Marie.

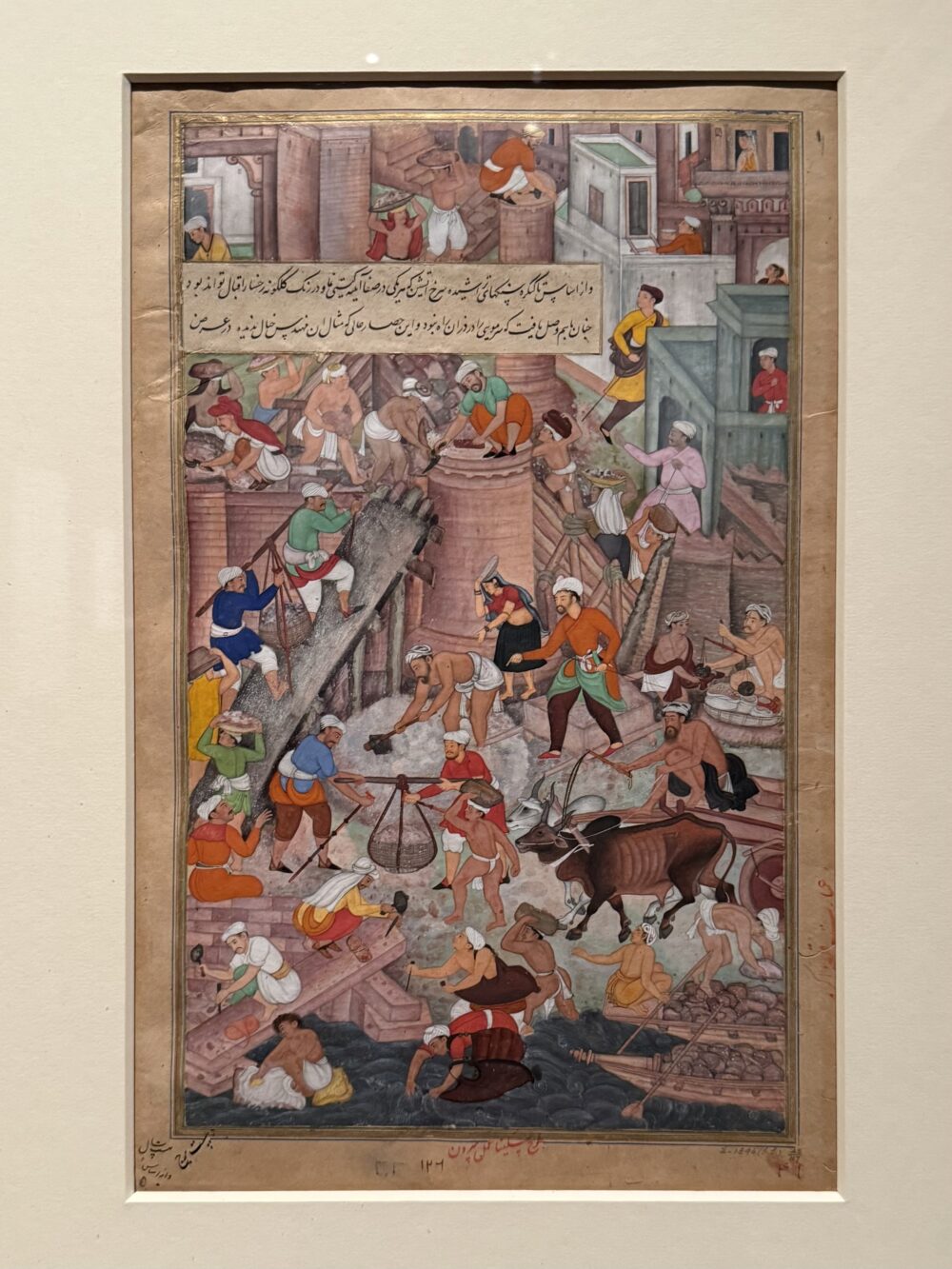

The book’s central device is strikingly intimate: photographs depicting the aftermath of their encounters, typically showing clothes discarded around their apartment or other settings. Each photograph is paired with independent reflections from both authors, exploring the memories and emotions these snapshots evoke.

Ernaux and Marie beautifully intertwine two contrasting experiences: the deeply challenging reality of cancer treatment, usually viewed as purely negative, and the exhilaration of their affair, typically seen as positive. The intermingling of these experiences felt profoundly true to life—highlighting the complexity of our emotional landscape, where joy and sorrow coexist in constant interplay.

As ever, Ernaux’s writing is exceptional. Her prose remains reflective, vivid, and emotionally honest, making the book not just insightful but deeply moving. The narrative flows effortlessly—I found myself eagerly turning the pages, absorbed by the nuanced interplay of reflection and vulnerability.

I found this both compelling and poignant—an exceptional exploration of intimacy, memory, and life’s contradictory beauty.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Alison L Strayer, Annie Ernaux, Marc Marie.