‘Cosmicomics’ by Italo Calvino

There’s a particular part of my brain that only ever lights up when I read Calvino. I don’t know quite how he does it. The stories are often absurd, abstract and utterly unmoored from reality—and yet they always end up saying something simple and profound about what it means to be human. I suppose that’s the trick, isn’t it?

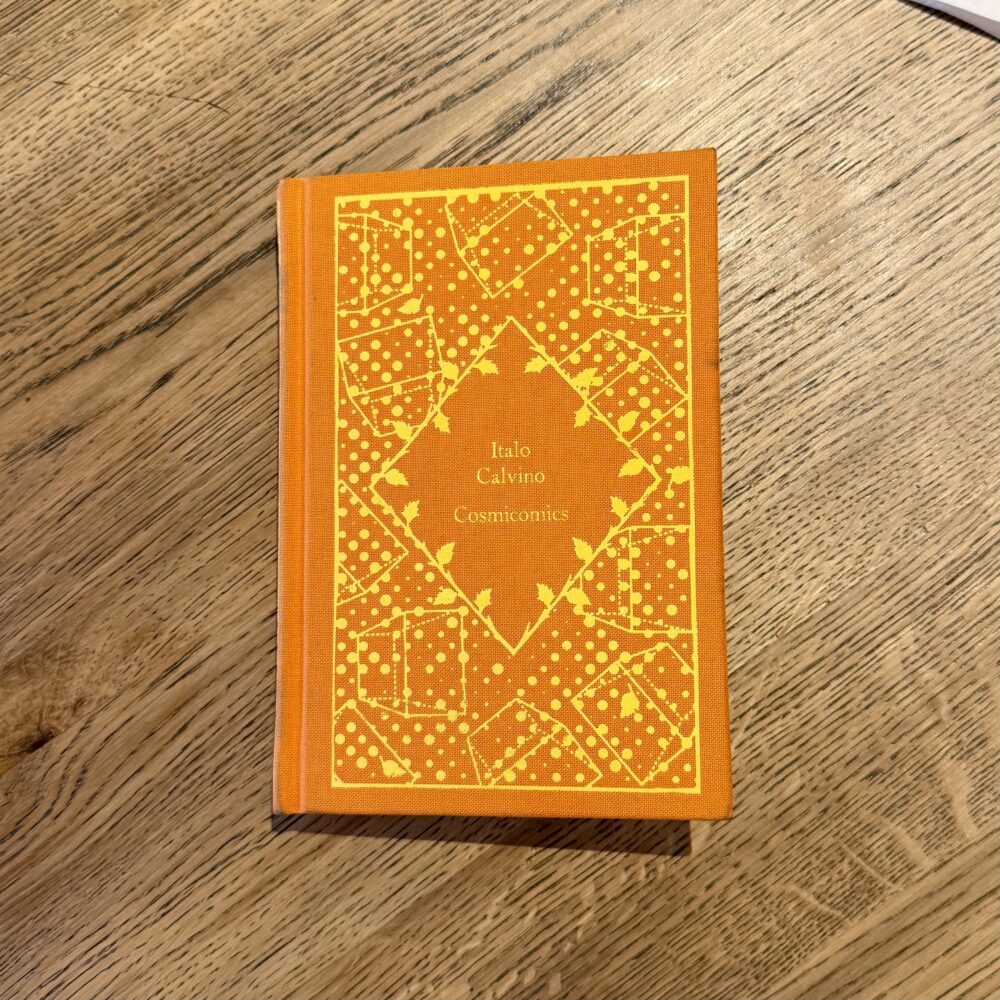

I stumbled across Cosmicomics more or less by accident: I hadn’t even realised there was a Calvino I hadn’t read. Penguin’s Little Clothbound Classics edition caught my eye, and I ended up reading it across a smattering of cafes, Metro journeys, and odd pockets of time. It’s a collection of short stories, each inspired by a scientific theory—most of which have since been disproven. But the facts are irrelevant. The stories are timeless.

In one, the moon is so close to Earth that people climb up to it on ladders and gather moon milk. In another, a generational culture clash is played out between an amphibian and his fishy uncle. In yet another, dinosaurs become mythical creatures whose presence haunts the collective imagination long after their actual threat has vanished. There’s even a story about a message that travels between planets over millions of years—a surprisingly prescient allegory for social media and the gnawing anxiety of being seen but not understood.

The stories sound bonkers. And they are. But they are also beautiful. There’s a real emotional clarity running through them—a sort of quiet, reflective core that anchors the whimsy. Calvino plays everything straight, and that’s part of what makes it work. If anyone else tried to write a story about a shy dinosaur feeling displaced in a post-dinosaur world, I’d probably scoff. But in Calvino’s hands, it becomes a meditation on trauma, resilience, and the shifting nature of memory. It reminded me of the way intense fears can linger long after the actual danger has passed. Over time, those feelings mellow and morph. Some traumas fade into something almost mythical: half-remembered, oddly unreal, occasionally even a little funny. Calvino captures that process perfectly.

The story Light Years, about delayed communication across space, struck a similar chord. It starts with a message—‘I saw you’—and unfolds into a deeply resonant exploration of guilt, miscommunication, and the irrelevance of context once enough time has passed. That gap between action and response, intention and perception, felt painfully familiar. It’s extraordinary how a story written in the 1960s can feel so bang on about our digital present.

If Calvino’s better-known work feels like fairy tales for grown-ups, Cosmicomics is something slightly different: more cosmological, more playfully abstract. And yet, it’s still unmistakably him. The whimsy. The philosophical undertow. The gentle humour and unshowy wisdom. It’s all there, just seen through the lens of space and time rather than gardens and cities.

The edition itself is a treat—a pocket-sized hardback in Penguin’s Little Clothbound Classics range, with the original William Weaver translation. It felt like an indulgent thing to hold and read, which added to the pleasure.

I’ve read too much Calvino to have any sensible opinion about whether this is a good place to start. But for me, it was a joy—amusing, moving, intellectually playful, and oddly comforting. Like all the best Calvino, it made me feel more human. And a little more okay with the fact that none of us really know what we’re doing.

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Italo Calvino.