Blue skies

I know I bang on about it more than I should, but—for a city dweller—I am so lucky to have such a bucolic walk to and from work.

This post was filed under: Photos, Newcastle upon Tyne.

I know I bang on about it more than I should, but—for a city dweller—I am so lucky to have such a bucolic walk to and from work.

This post was filed under: Photos, Newcastle upon Tyne.

The first posts on this blog were written when I was 18 years old. When Françoise Sagan was 18, her novel was published. It is impossible to imagine what it must be like to have Sagan’s wisdom and insight at such a young age: the proof that I had none of it is abundant on this very website.

Bonjour Tristesse, which I read in Heather Lloyd’s translation, opens with a seventeen-year-old girl, Cécile, living with her widowed father, Raymond. They live a carefree, perhaps mildly hedonistic life together in the French Riviera. Raymond is a bit of a playboy, and Cécile enjoys the freewheeling nature of their existence.

This is challenged when one of Raymond’s former lovers, Anne, turns up. As Raymond and strait-laced Anne become closer, Cécile fears that a degree of predictable rigidity is entering their lives. She seeks to fight against it by engineering the end of Raymond and Anne’s relationship.

Cécile’s meddling has consequences foreseen and unforeseen, which she is then forced to come to terms with—and that jolting realisation catapults her into adulthood.

This was published and set in 1954, but certainly stands the test of time. It’s an entertaining read with real depth below the surface, and no shortage of humour. It may only be a short book—perhaps more a novella than a novel—but there is a lot packed into it. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Here are some passages I highlighted:

‘You don’t realize how pleased with herself she is,’ I cried. ‘She congratulates herself on the life she has had because she feels she has done her duty and …’

‘But it’s true,’ said Anne. ‘She has fulfilled her duties as a wife and mother, as the saying goes …’

‘And what about her duty as a whore?’ I said.

‘I dislike coarseness,’ said Anne, ‘even when it’s meant to be clever.’

‘But it’s not meant to be clever. She got married just as everyone gets married, either because they want to or because it’s the done thing. She had a child. Do you know how children come about?’

‘I’m probably less well informed than you,’ said Anne sarcastically, ‘but I do have some idea.’

‘So she brought the child up. She probably spared herself the anguish and upheaval of committing adultery. She has led the life of thousands of other women and she thinks that’s something to be proud of, you understand. She found herself in the position of being a young middle-class wife and mother and she did nothing to get out of that situation. She pats herself on the back for not having done this or that, rather than for actually having accomplished something.’

‘I detest that kind of remark,’ said Anne. ‘At your age it’s worse than stupid, it’s tiresome.’

I normally avoided university students, whom I considered to be coarse and preoccupied with themselves and, above all, preoccupied with their own youth: to them just being young was a drama in itself, or an excuse for being bored.

I was greatly attracted to the concept of love affairs that were rapidly embarked upon, intensely experienced and quickly over. At the age I was, fidelity held no attraction. I knew little of love, apart from its trysts, its kisses and its lethargies.

I did not want to marry him. I liked him but I did not want to marry him. I did not want to marry anyone. I was tired.

We met Charles Webb and his wife at the Bar du Soleil. He specialized in theatre advertising and his wife specialized in spending the money he made, which she did at an incredible rate by lavishing it on young men.

How difficult she made life for us, with her sense of dignity and her self-esteem!

This post was filed under: What I've Been Reading, Françoise Sagan, Heather Lloyd.

The association between Los Angeles, cars and traffic is well documented—not least in decades of Hollywood movies. Christopher Grimes had a pessimistic, or perhaps realistic, article in the Financial Times last week about the latest efforts to convince Angelenos to try public transport.

But here’s the thing: my mental conception of the city is completely different.

Wendy and I have visited Los Angeles exactly once, six years ago. This Amtrak train delivered us there.

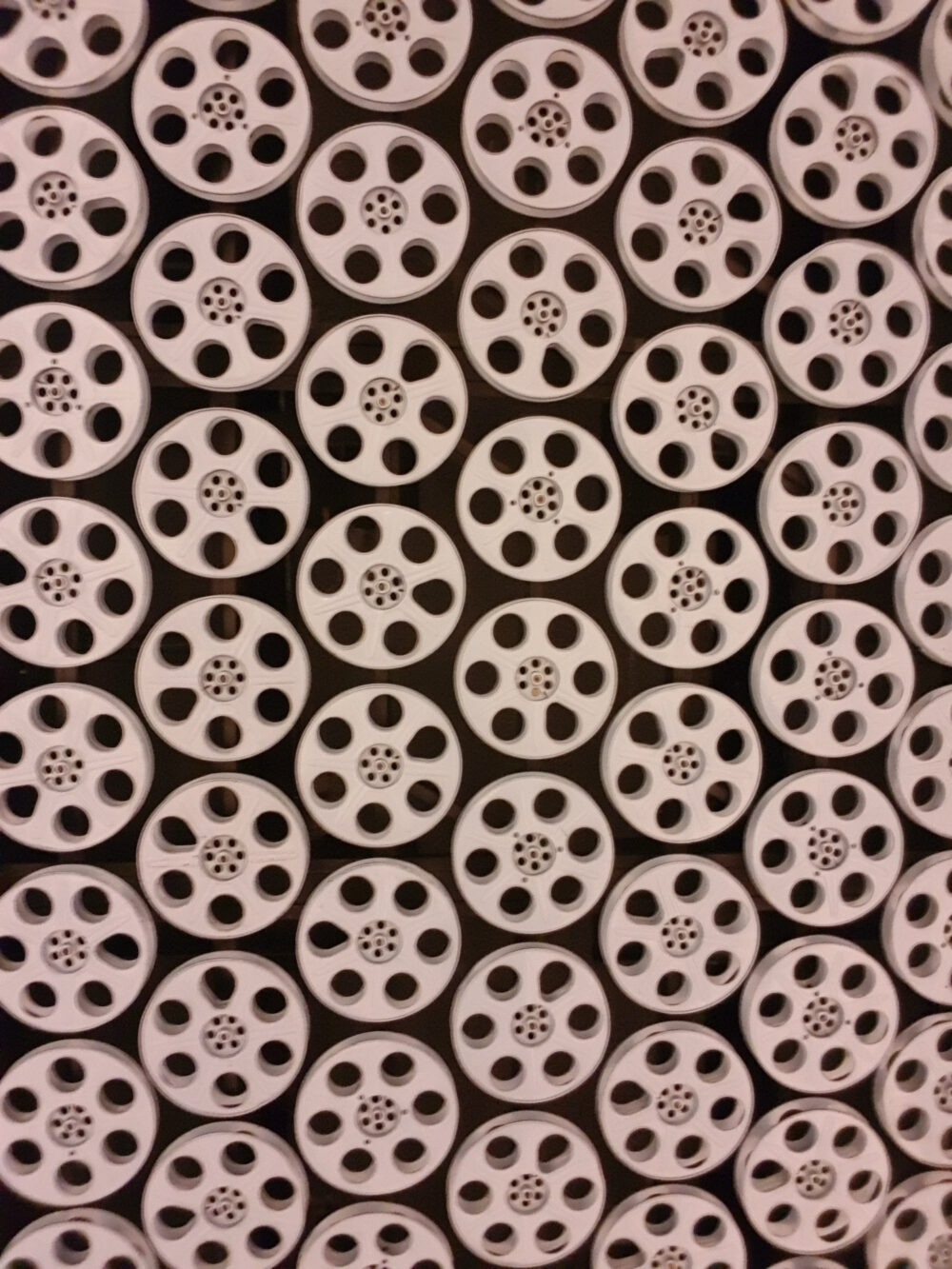

We explored the city on foot and by Metro. Perhaps as a consequence, when I think of Los Angeles, my memories are inextricably caught up with public transport. I think of the grand architecture of Union Station and the whimsical decoration of some of the Metro stops, like these film reels at Hollywood/Vine:

Oh, and I remember my efforts to forget about work being undermined by these public health messages, which seemed to be everywhere:

But what I absolutely don’t think of is cars, freeways and traffic—despite them being so clearly a major part of life for those who live in the city.

It’s a tidy reminder of how experiences of a city can vary, and how a brief visit can leave one with completely the wrong impression of what a place is really like to live in.

This post was filed under: Travel, Christopher Grimes, Financial Times, Los Angeles.

We’ve done windmills recently, but here’s another one that Wendy and I visited recently: the ruined Calhau windmill in the Monsanto Forest Park in Lisbon. It dates back to the 18th century when Lisbon was full of windmills. It is, erm, no longer operational.

After some serendipitous channel-hopping, Wendy and I were captivated by Friday’s press conference by Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, stranded on the International Space Station. Suni, especially, seemed remarkably grounded and professional in the midst of what must be an extraordinarily trying circumstance for anyone.

In Ars Technica, Stephen Clark’s invocation of their status of Navy captains who have abandoned ship—or, whose ship has abandoned them—perhaps gives a peek into the professional disappointment that this turn of events must hold for the pair. One wonders whether the safe , unscrewed return of the Starliner compounds or alleviates that heaviness.

I’m reminded, too, of the stories of early astronauts being looked down upon among test pilots based on the view that they were essentially passengers on vehicles that flew themselves. It’s hard not to wonder whether the safe return of Starliner stirs up those emotions in Suni and Butch as well.

There must be a lot on their minds—but you’d never know it to listen to them.

This post was filed under: Technology, Ars Technica, Butch Wilmore, Space, Stephen Clark, Suni Williams.

I suspect the fact that I recognise Chiwetel Ejiofor mainly from the British Airways safety video does not reflect well upon me, even as someone who doesn’t watch many films. But now I also know him for Rob Peace, a film for which he wrote the adaptation of the book, directed, and starred in, playing the titular character’s father.

This is a biographical film. Rob Peace is shown to be a precocious child born to a poor, black family in the US in 1980. During his childhood, his father is imprisoned for murder, though his family has doubts about the safety of the conviction. With a lot of hard work, Peace ends up securing a place at Yale. He begins to sell drugs while there to fund his father’s appeal, and the discovery of this plot puts paid to his desire to pursue a doctorate.

He moves onto a real estate career through which he intends to improve the neighbourhood in which he grew up, though his longer-term plans are scuppered by the financial crash. He once again takes to selling drugs in order to refund the money his friends had invested in his venture, though he is shot dead in the process.

Biography is hard, and it seems to me that biography on film must be even harder: how do you cram a life into a couple of hours? This film doesn’t quite crack that nut: it’s tonally uneven, and it does a lot of ‘telling’ rather than ‘showing’, sometimes in quite peculiar ways. For example, we are told that Peace has a particular talent for bringing people together and that a party he has organised has an attendance list drawn from many different social groups, rather than shown this. He has a romantic relationship which we don’t see enough of to be truly invested in, but also shown more than just a ‘hint’ of. Some of the choices struck me as downright odd.

The other issue with this film—and it’s surely one of the challenges of biography—is that I don’t think it gets the balance right between the focus on its subject and the ripples of influence they have. Everything here is focused on Peace: we don’t really get to understand and appreciate his positive impact on others (though his housing project, for example), nor any negative impact (upon the people to whom he sold drugs, for example). This left it feeling a little bit insular, and it felt like this undercut the film’s attempt to meaningfully dive into some of the bigger social challenges the film raises.

But, nevertheless, I enjoyed this. This didn’t completely work for me, but I would like to see more of this sort of thing: it was close to being excellent.

The film was carried by its main star, Jay Will, who is magnetic and completely believable in the role. He must surely have a huge acting career ahead of him. Weirdly, I thought the weakest link among the actors was Ejiofor himself, whose character seemed utterly inconsistent from scene to scene—though perhaps this was more the fault of his writing than his acting.

I think this is worth going to see.

This post was filed under: Film, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Jay Will, Rob Peace.

I enjoyed this extract from Oliver Burkeman’s book, Meditations for Mortals, and this imagery in particular:

A pair of images that help clarify things here are those of the kayak and the superyacht. To be human, according to this analogy, is to occupy a little one-person kayak, borne along on the river of time towards your inevitable yet unpredictable death. It’s a thrilling situation, but also an intensely vulnerable one: you’re at the mercy of the current, and all you can really do is to stay alert, steering as best you can, reacting as wisely and gracefully as possible to whatever arises from moment to moment.

That’s how life is. But it isn’t how we want it to be. We’d prefer a much greater sense of control. Rather than paddling by kayak, we’d like to feel ourselves the captain of a superyacht, calm and in charge, programming our desired route into the ship’s computers, then sitting back and watching it all unfold from the plush-leather swivel chair on the serene and silent bridge.

The point Burkeman is making is about knuckling down and actually doing the things one wants to do in life, but I liked this imagery more for its root in stoicism. Life is unpredictable, and the best laid scheme gang aft agley, as Rabbie Burns had it.

But I think there is something in Burkeman’s recognition that there can be ‘wisdom’ and ‘grace’ in the response. I usually associate those qualities with well-laid plans which come off, but Burkeman helped me to remember that it’s demonstrating them in the face of unexpected challenge which is both the most difficult and the most worthy outcome.

And it’s also a reminder that when we look at others and perceive them to be in their own superyachts gliding towards some goal, we are mistaken: in the end, we’re all in kayaks, and we’re all at the mercy of fortune and the unknown.

The image at the top of this post was generated by DALL·E 3.

This post was filed under: Miscellaneous, Oliver Burkeman.

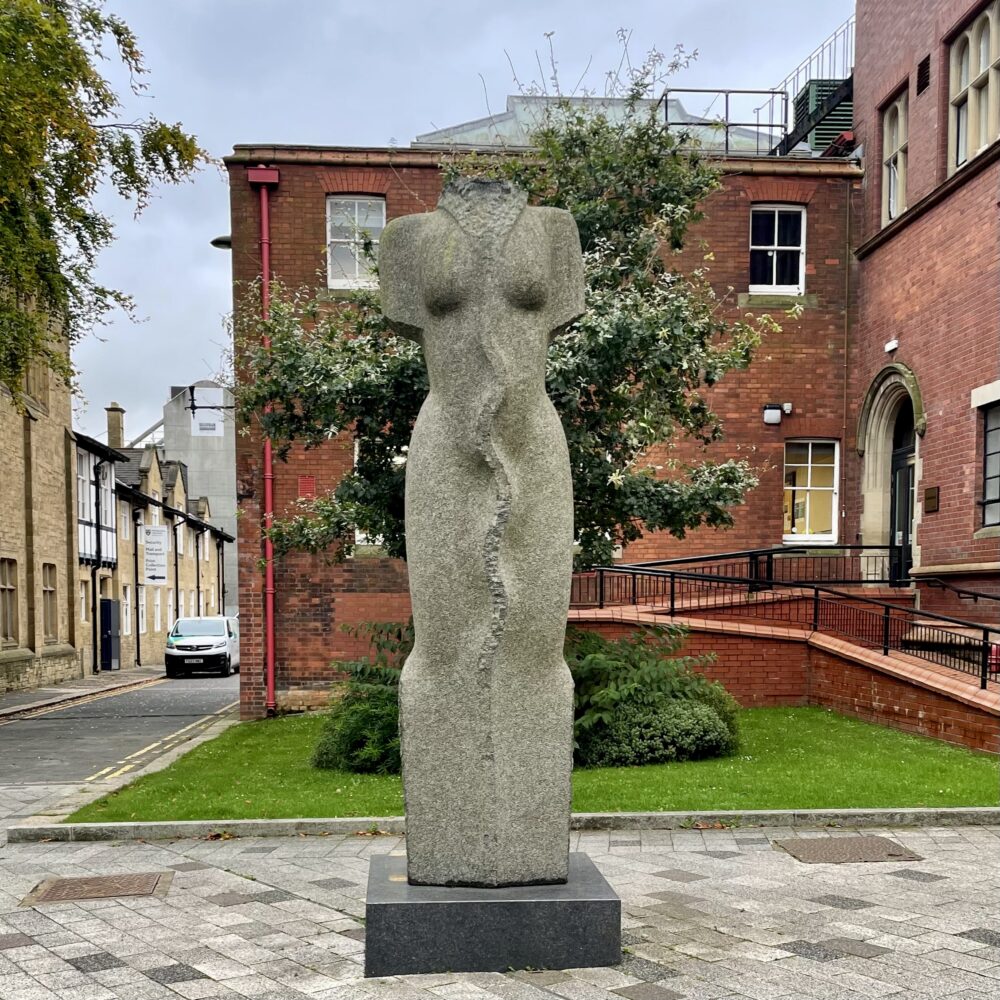

Pillar Man, which I showed you a few days ago, isn’t Nicolaus Widerberg’s only sculptural contribution to Northumbria University: he has quite a few scattered around the place.

This 2013 piece is called Collar and Wave.

This post was filed under: Art, Photos, Newcastle upon Tyne, Nicolaus Widerberg, Northumbria University.

I have an on-off relationship with physical notebooks. Only last year, I mentioned that I transitioned to using OneNote; yet today, I’m back to using a combination of OneNote and a paper notebook from Papier.

I therefore very much enjoyed this book excerpt by Roland Allen in The Walrus about the history of Moleskine—the notebook manufacturer to whose paper diaries Wendy is especially loyal.

The non-standard dimensions, a couple of centimetres narrower than the familiar A5, let you slip the notebook into a jacket pocket, and the rounded corners—which add considerably to the production cost—help with this. They also stop your pages from getting dog-eared and, together with the elastic strap and unusually heavy cover boards, confirm that the notebook is ready for travel. The edges of the board sit flush with the page block, ensuring that your Moleskine can never be mistaken for a printed book. In use, it lies obediently open and flat, and the pocket glued into the back cover board invites you to hide souvenirs—photos, tickets stubs, the phone numbers of beautiful strangers. Two hundred pages suggest that you have plenty to write about; the paper itself, tinted to a classy ivory shade and unusually smooth to the touch, implies that your ideas deserve nothing but the best, and the ribbon marker helps you navigate your musings. Discreetly minimal it may seem, but the whole package is as shot through with brand messaging as anything labelled Nike, Mercedes, or Apple—and, like the best cues, the messaging works on a subconscious level.

My Papier notebook, I note, does not exhibit all of those features, and would be better if it did. I particularly liked the article’s take on the little leaflet that’s tucked inside Moleskine notebooks:

The leaflet opened with a lie (the new Moleskines were not “exact reproductions of the old”) then immediately veered toward gibberish, but that didn’t matter. Pound for pound, those seventy-five words proved themselves among the most effective pieces of commercial copywriting of all time, briskly connecting the product’s intangible qualities—usefulness and emotion—to its material specification, thereby selling both the sizzle and the steak. Sebregondi and Franceschi picked an astutely international selection of names to drop: an Englishman, an American, and a Frenchman encouraged cosmopolitan aspirations. “Made in China,” on the other hand, did not, so they left that bit out.

It’s one of those articles which is packed with insights and titbits I’ve never thought to wonder about, and I’d highly recommend giving it a few minutes of your time.

The image at the top of this post was generated by DALL·E 3.

This post was filed under: Miscellaneous, Roland Allen, The Walrus.

The content of this site is copyright protected by a Creative Commons License, with some rights reserved. All trademarks, images and logos remain the property of their respective owners. The accuracy of information on this site is in no way guaranteed. Opinions expressed are solely those of the author. No responsibility can be accepted for any loss or damage caused by reliance on the information provided by this site. Information about cookies and the handling of emails submitted for the 'new posts by email' service can be found in the privacy policy. This site uses affiliate links: if you buy something via a link on this site, I might get a small percentage in commission. Here's hoping.