I’ve been to visit ‘Visions of Ancient Egypt’

When I decided to post every day in 2023, I didn’t expect to be on my third Egypt-themed post by March. Yet, last year’s centenary of the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb has sparked a renewed fascination in all things ancient Egypt, and so after Hieroglyphs and a coffin, I’ve been to see some art.

This exhibition by the Sainsbury Centre explores artistic responses to ancient Egypt, including all sorts of objects from paintings to pottery, and dresses to neon lights.

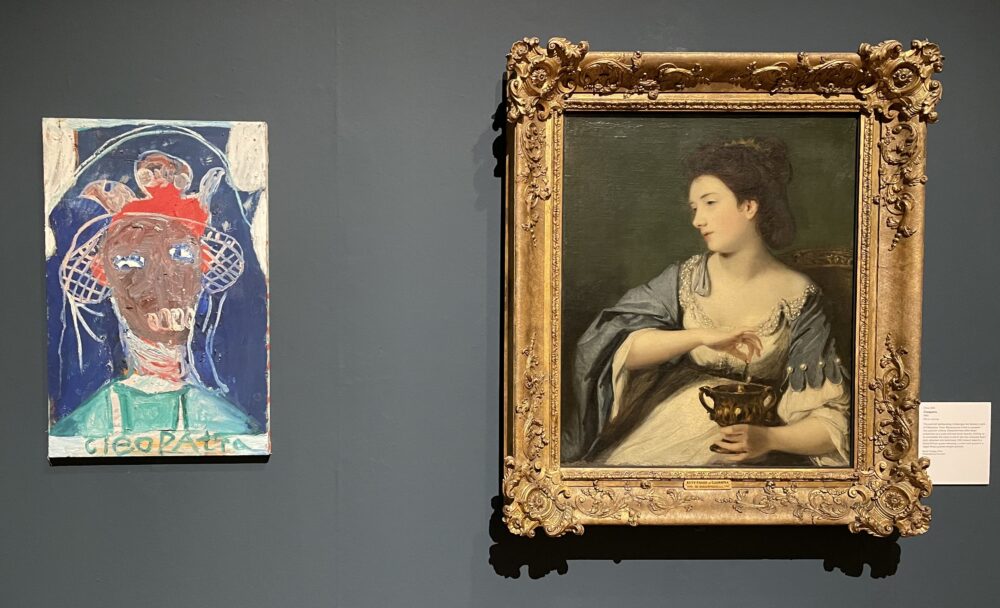

The first pair of objects in the exhibition make a clear statement of intent for the exhibition as a whole. Joshua Reynolds’s 1759 oil painting, Kitty fisher as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl (to demonstrate her wealth) shows Cleopatra as we hear about her in Western myth: an extravagant, white seductress. Using the same medium in 1992, Chris Offil paints Cleopatra as a black African queen, shorn of the imposed Western myth.

This exhibition taught me how much of what we imagine to be ‘ancient Egyptian’ is anything but: much of it is actually reflective of other cultures. Before this exhibition, I didn’t know how much of ‘Egyptian’ style was actually Roman, the Romans having conquered Egypt in 30BC and Roman objects having been misattributed to ancient Egypt. Wedgwood, who pioneered ‘Egyptian’ designs in pottery, was actually (unknowingly) working from Roman artefacts–and never actually visited Egypt himself.

Before I visited this exhibition, I think I vaguely knew that The Times had an exclusive deal with Howard Carter for the photographs of his excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb. It’s the sort of thing newspapers like to celebrate. But I hadn’t previously understood that this exclusivity applied even within Egypt, depriving Egyptians of coverage of one of the most significant archeological findings in their country’s history… hardly something to be proud of in retrospect.

This exhibition features several watercolour paintings by Howard Carter, recording decorations that he uncovered during excavations, necessary in his early career as photography wasn’t an option. I had no idea that he was a talented artist, and I’d never really considered the necessity for archeologists to be able to paint and draw.

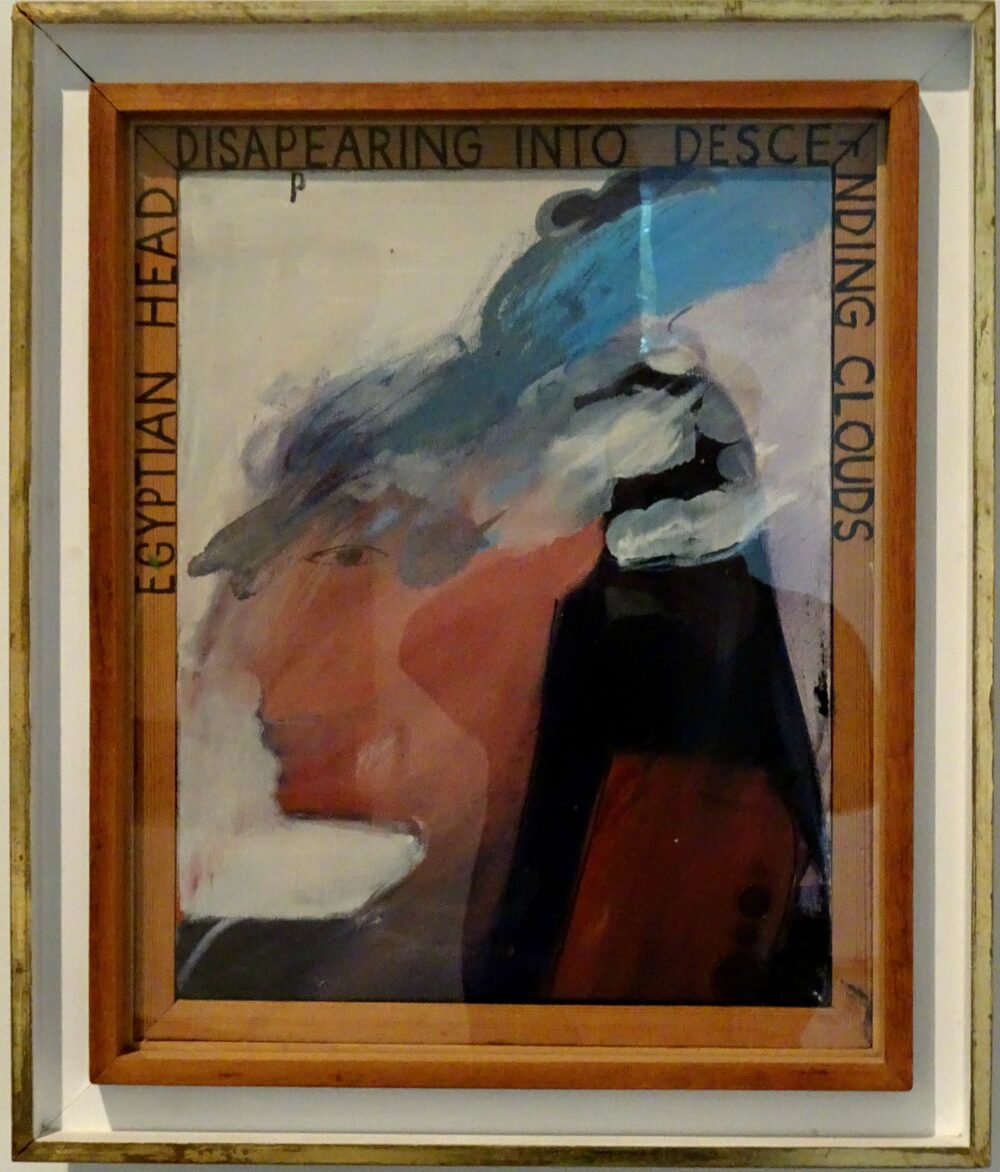

The exhibition closed with David Hockney’s 1961 Egyptian Head Disappearing Into Descending Clouds. This was an inspired choice. I wandered through the doors and tried to ponder exactly how I’d think of ancient Egypt in the future, given that all of my existing pre-conceptions had been blown away.

This was an exhibition that taught me things, corrected my misconceptions, and made me think: more than either of the other Egyptian things I’ve seen this year. I thought it was excellent.

Visions of Ancient Egypt continues at The Laing until 29 April.

A quick note about the photos in this post. The one at the bottom is a picture I’ve ‘borrowed’ from the David Hockney Foundation. The one at the top is a photo I took during the exhibition, before I realised that photography was banned… oops. I’m ummed and ahhed about whether I should include it given that I shouldn’t have taken it, but decided that it was such a great piece of curation that it deserved celebrating. Sorry, if you think I shouldn’t have done that.

This post was filed under: Art, Post-a-day 2023, Newcastle upon Tyne, The Laing.