When thinking about risk assessment, it is often useful to separate the hazard (the bad thing that might happen) from the risk (the hazard plus the likelihood of it occurring). Things which are quite hazardous (wild tigers) can be low risk if they’re unlikely to cause harm (there aren’t any wild tigers in the UK). And things which can seem non-hazardous (coconuts) can be high risk if very likely to cause harm (perilously dangling above someone’s head on a windy day).

In a conversation recently, someone commented in passing that it wasn’t possible to meaningfully assess risk when a hazard is so large as to be unquantifiable: say the end of the earth, a world war, or a global pandemic.

I entirely disagree.

Firstly, no hazard is unquantifiable large: of the examples cited, a pandemic is less hazardous than the apocalypse.

But even ignoring that point, it’s self-evident that an activity with a low likelihood of causing the apocalypse is lower risk than one with a high likelihood of causing the apocalypse.

“Okay,” you might say, “but what I really meant is that you can’t compare with between hazards because the apocalyptic one will always win out.”

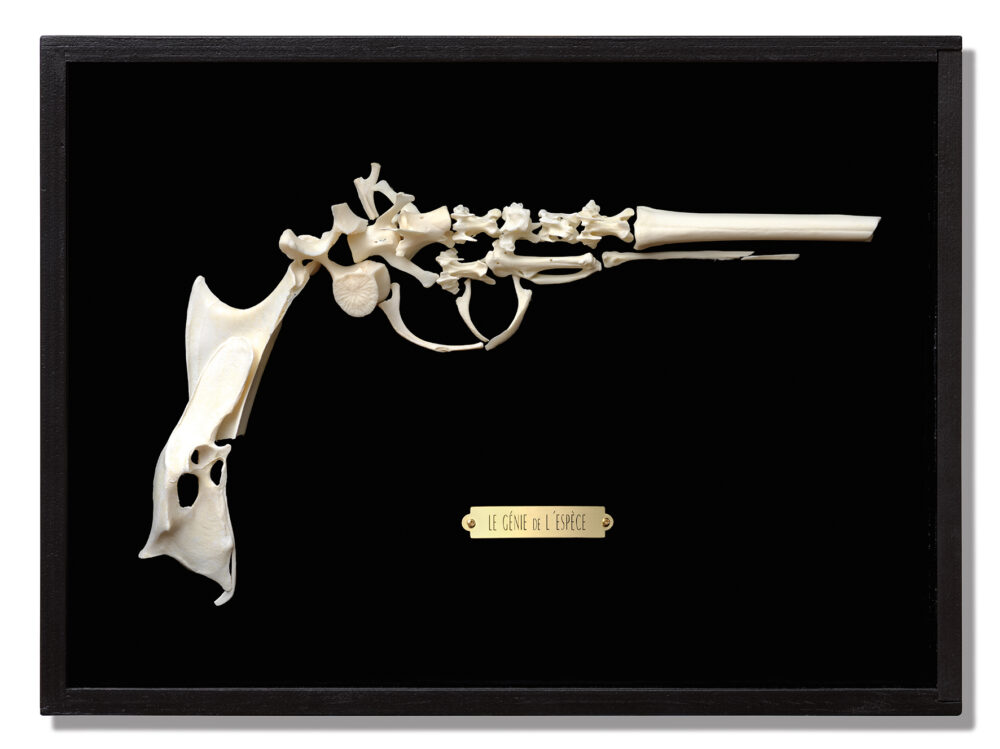

But that’s nonsense too. A threat with a negligible likelihood of causing a cataclysmic event is self-evidently lower risk than a threat with an extremely high likelihood of killing someone. Firing a gun in a crowded place is riskier than allowing visitors to tour nuclear power plants, even though there is an infinitesimally small chance of the latter being the start of a chain of events that leads to a nuclear disaster.

One could spend a lifetime trying to derive where the lines lie: and, indeed, as a society, we do just that. Through time, democracy, effort and research, we try to reach a societal consensus on where the balance of risks lies. We end up taking actions that have potentially world-ending consequences (say, building nuclear weapons) because we believe it’s the least risky approach.

In reality, risk assessments are generally much more complex than this implies: the theoretical balancing of risks is often easier than understanding the likely effects of each course of action. Any given action (or inaction) has myriad effects, only a fraction of which are pertinent to the specific risk under consideration.

In medicine, giving antibiotics might reduce the risk of a bacterial infection ending someone’s life. It may also cause side effects for an individual, including death. When applied as a general rule in guidance, it will also have extensive wider societal implications: financial cost, the opportunity cost of choosing to prescribe antibiotics rather than spending time doing something else, antimicrobial resistance, and so on. Not giving antibiotics is also very likely to have a whole host of implications, which take effort to foresee. And both courses of action will almost certainly have unforeseeable consequences, too.

The process of working out the implications of each course of action can become enormously complicated, and can often be extremely uncertain. But it must be done because we must make a decision.

In medicine, at least, well-written and considered guidelines constantly try to take a reasoned, explained judgement as to which path is most likely to lead to net benefit in most circumstances. NICE, for example, is typically great at explaining its committees’ thinking on these things—and also great at changing guidance when the real world implications of implementation turn out to differ from predictions.

But sadly, not all guidelines are well-written and considered. Astonishingly, I still come across newly published guidance which reports that intervention X will reduce the risk of disease Y, with no consideration even of side effects for individual patients, let alone wider societal consequences. The guidance vacuously recommends X based on its impact on Y alone.

If Y is common but mild and self-limiting, and X is extraordinarily expensive, then prescribing X will rarely be justified.

If the risks are such that you’d need to prescribe 3,000 doses of X to prevent one case of disease Y, and X has common side effects, then prescribing X may not be justifiable.

It shames my profession that some of this faulty guidance is public health guidance—the part of the medical profession that ought to be most attuned to accounting for costs and unintended consequences.

Balancing risks can be very hard, but it is always possible and indeed always necessary, especially in medicine.